EV Consumer

Behavior

JUNE 2021

Ricardo Inc.

Detroit Technical Center

Van Buren Twp., MI

48111 USA

©2021 Fuels Institute

Disclaimer: The opinions and views expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the individuals on

the Fuels Institute Board of Directors and the Fuels Institute Board of Advisors or any contributing organization to

the Fuels Institute. The Fuels Institute makes no warranty, express or implied, nor does it assume any legal liability

or responsibility for the use of the report or any product or process described in these materials.

1

Ricardo Strategic Consulting

(“Ricardo”) conducted a literature

review to better understand how and

where consumers drive and recharge

their electric vehicles (EVs) and what

they would like to experience while

recharging in terms of site design,

amenities, capabilities, and services.

Ricardo has also analyzed existing literature to

both understand current consumer behavior and

anticipate how it could evolve over the next 10 years

as more consumers purchase EVs. This exercise has

been focused on answering five questions:

1. Who is the customer?

2. When and where does the customer recharge?

3. Why does a customer choose a particular

recharging facility?

4. How do customers interact with

charging equipment?

5. What do customers do at facilities

while charging?

This literature review included various publicly

available sources such as existing Ricardo research

on consumer preferences; published surveys;

federal, state, and local government publications;

cross-functional organization publications; scholarly

articles; university/institute publications; national

lab publications; public policies; and press reports.

This was supplemented with persona interviews to

exemplify findings.

Key findings that emerged from the literature review

are below:

Who is the customer?

• The top demographic of 2019 EV owners are

middle-aged white men earning more than $100,000

annually with a college degree or higher and at least

one other vehicle in their household.

• 37% of Democrats and 34% of Republicans

appear to view EVs positively, and a guaranteed

$7,500 tax rebate could make 78% of Democrats

and 71% of Republicans more likely to consider

an EV during their next purchase or lease (2019).

FUELS INSTITUTE

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Electric Vehicle Consumer Behavior

2

FUELS INSTITUTE | EVC | EV CONSUMER BEHAVIOR

• EV sales have grown exponentially over the past

10 years; however, the ownership demographic

has remained relatively the same. The average EV

owner continues to be male, aged 40-55 years old,

with an annual household income of more than

$100,000 (2019). Mileage driven, however, has

increased from 100 miles to 250 miles a week over

the years.

• In the next 10 years, EV sales are expected to

constitute between 12% and 40% of all light-duty

vehicle sales, implying that:

• EV buyer age could normalize with the broader

new vehicle buying trend

• EVs could become more aordable

• Number of EV buyers with no provision to

charge at home could increase

• Driving pattern is expected to be similar to the

way internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles

are driven

• Gender distribution could become more

balanced

• EV fleet sales are expected to grow in the

upcoming years, driven by state mandates.

• Household income, family size, age, driving

distance, geographical location, and type of

residence tend to influence EV ownership.

• Total cost of ownership (TCO) and payback

period are the key drivers in a business’ decision

involving adoption of EVs in their commercial fleet.

• Aordability, availability, and familiarity appear

to be amongst the key factors influencing

likelihood of EV purchases.

• EV trips are mostly planned with charging

locations in mind, unlike conventional vehicles;

however, more daily miles are driven on average

in an EV (2020) than in an ICE-powered vehicle.

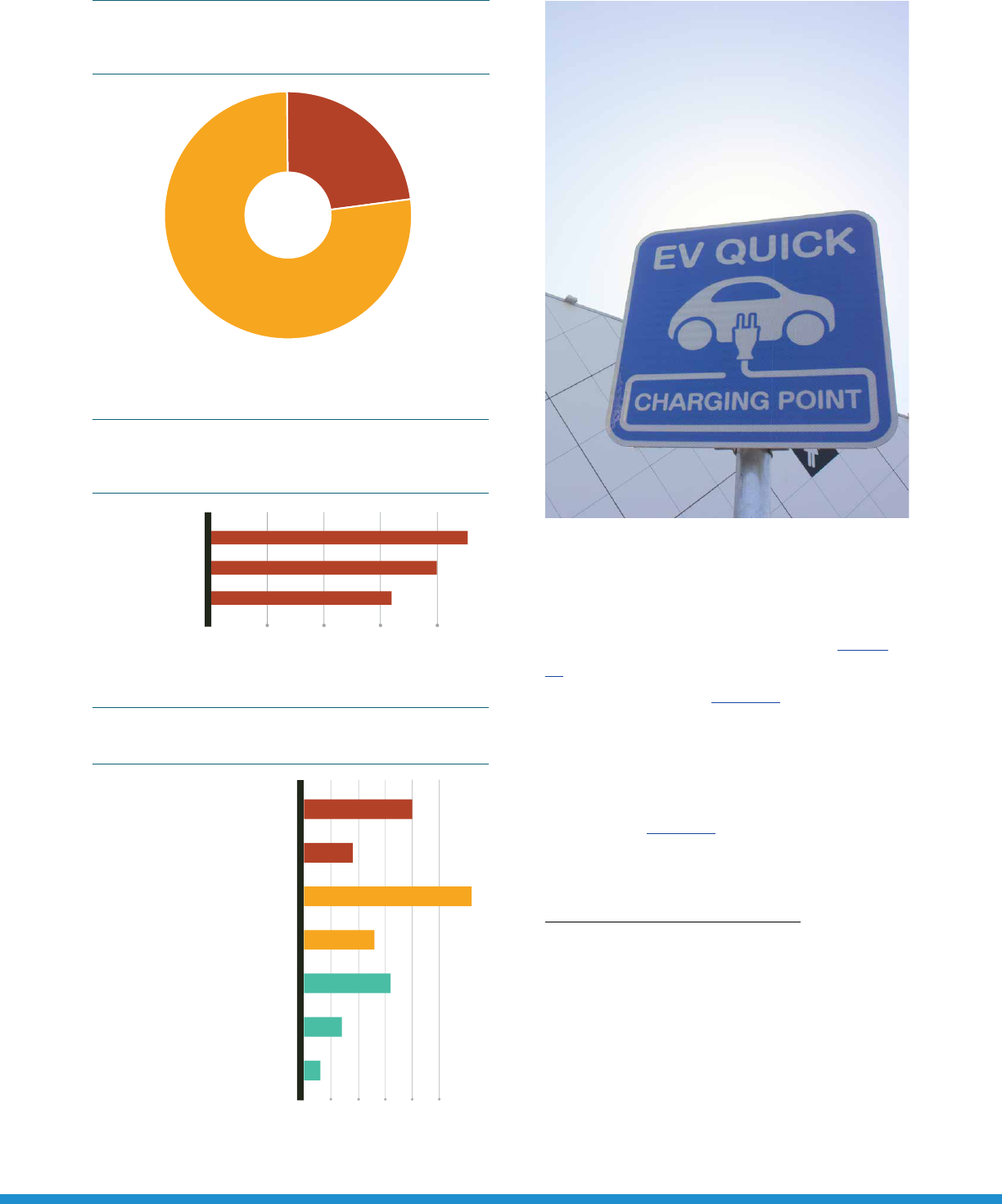

When and where does the customer recharge?

• EV drivers tend to recharge daily or once every

two days, typically overnight at home, and

overall, about 70-80% of charging occurs at home

or at a workplace parking lot.

• Most EV fleet customers today (2020) operate in a

hub-and-spoke network and exclusively recharge

their vehicles overnight at their home base.

• The most used public chargers are those where

vehicles are typically parked for long periods

(e.g., airport parking lots, grocery store, etc.)

(2012-2014).

• Most customers drive within their battery range

only, using a public charger when making trips

longer than their range would permit.

• Drivers of ICE vehicles fill up based on the cost,

necessity, and time of the day; 32% only fill

up when they see the fuel warning light in the

dashboard (2019).

• Nonavailability of chargers at home and making

trips longer than the battery range are two of

the various reasons why drivers use public

charging stations.

• EV charging stations spaced 70 miles from each

other on average could provide convenient access

to battery electric vehicle (BEV) drivers across the

interstate system (2017).

3

FUELS INSTITUTE | EVC | EV CONSUMER BEHAVIOR

Why does the customer choose a particular public

recharging facility?

• EV drivers tend to base their choice of public

chargers on various factors, including: speed of

charging, need for charging, brand of the charger,

compatibility with the electric vehicle supply

equipment (EVSE), dependability, availability,

identity of charging host/facilities available

(e.g., grocery store, gym, etc.), payment options

available, and app/in-car interface suggestions.

• Dependability, convenience, cost of use, and

the need to travel beyond the EV’s battery range

appear to have the greatest influence in the

choice of charging location (2011-2019).

• Approximately 75% of today’s non-Tesla drivers

feel the current charging network is “somewhat”

or “very adequate” (2017).

• Approximately 46% of BEV drivers (2016) feel

availability of direct current fast charging (DCFC)

as a feature is not a very big influencer in their EV

buying decision.

• More than 80% of EV drivers use three charging

locations or fewer away from their home, where

they do most of their charging (2011-2014).

• The drivers’ decision in picking a brand of charger is

influenced by factors such as favoring the provider

of the default EV charge card (e.g., Hyundai Ioniq

has a ChargePoint card in the glovebox). Other

factors include being of the same brand as their

home charger, dependability of the network, avail-

ability in their primary area of operation of the

vehicle, and availability at the places they visit oen.

• Fewer than 5% of EV owners rely on smartphone

applications (“apps”) to find charging stations for

daily use, although many EV owners likely have a

charging app on their smartphone. Tesla models

have point-to-point trip planning with charging

integrated in the vehicle, and it is likely other

original equipment manufacturers (OEM) will

follow (2020).

• Today’s EV owners are not deterred by the

deficits of the current EV infrastructure and have

found ways around the limitations, but for mass

adoption, it is critical to understand views of

buyers who are not considering buying an EV

today (2020).

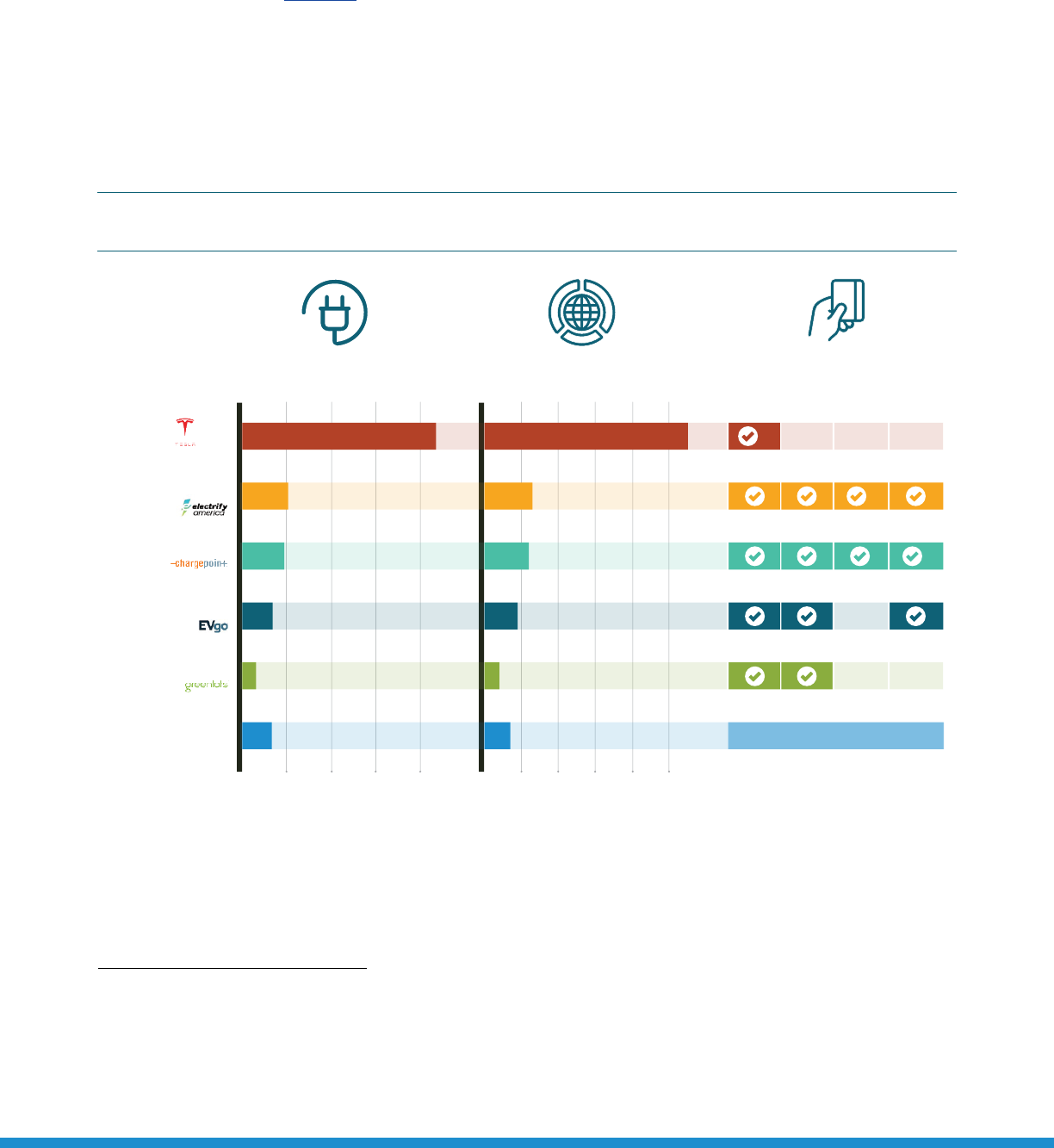

• How do customers interact with charging

equipment?

• Approximately 57% of surveyed EV drivers are

willing to pay a premium over at-home charging

rates to use a public Level 2 charger, and more

than half of EV drivers are willing to pay more

for DCFC compared to Level 2 charging when

convenient (2020).

• EV drivers preferred optimized charging and to be

billed by the kilowatt-hour (kWh) to attain a good

balance of cost and time (2016).

• Approximately 77% of people used mobile

payments last year, including 80% of 35- to

50-year-old U.S. residents; all top charging

network appear to support mobile

payments (2019).

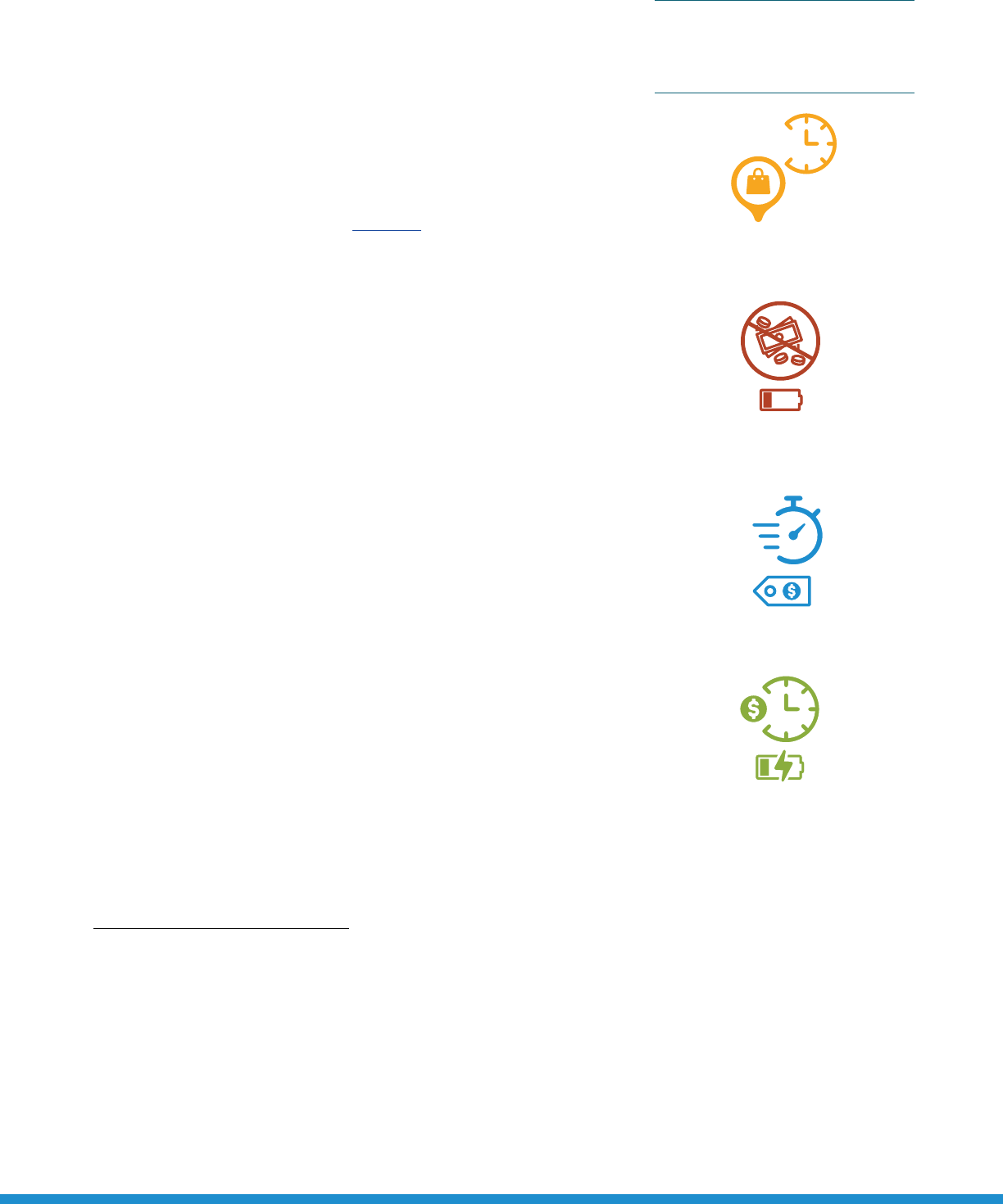

What do customers do at facilities while charging?

• Plug-in electric vehicle (PEV) consumers expect

to spend 30 minutes to one hour at the charger

(2019-2020). Some other studies/surveys suggest

that this consumer would prefer an event (15

minutes or less) to minimize downtime in their

daily routine. Grocery store visits, dining, and

shopping are the most preferred activities while

waiting for their EVs to be charged.

• Broadly, free charging while shopping tends

to increase dwell time. Kohls found that when

provided with free charging, EV owners spend

about $1 per minute within an hour window (2015).

• PEV drivers appear to prefer to run errands or to

be entertained while charging their vehicle at a

public charger (2019).

4

FUELS INSTITUTE | EVC | EV CONSUMER BEHAVIOR

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................................................01

INTRODUCTION

....................................................................................................................................................................... 06

Literature Study Context

...............................................................................................................................................................................06

Objective of the Study

................................................................................................................................................................................... 07

Personas

...................................................................................................................................................................................................................08

METHODOLOGY

......................................................................................................................................................................09

PROJECT REPORT

..................................................................................................................................................................10

Who Is the Customer?

...................................................................................................................................................................................10

Demographics

........................................................................................................................................................................................10

Evolution of EV Buyer Demographics and Behavior Over the Past 10 Years

.........................................16

Anticipated Evolution of EV Buyer Demographics and Behavior Over the Next 10 Years

..........18

Demographic Characteristics and Their Relationship With EV Ownership and Behavior

............20

Difference in Trips Taken in EVs Versus Liquid-fuel Vehicles

.................................................................................21

When and Where Does the Customer Recharge?

...................................................................................................................22

EV Drivers’ Charging Frequency

.............................................................................................................................................. 22

EV Drivers’ Preferred Recharge Location

...........................................................................................................................24

Factors That Influence a Recharge Occasion

.................................................................................................................. 26

Charging Infrastructure Requirement

.....................................................................................................................................27

Why Does the Customer Choose a Particular Public Recharging Facility?

............................................................28

Level 2 Charging Availability’s Influence on Consumer Perception of Availability,

Capacity, and Convenience Compared to DCFC Equipment

............................................................................. 28

Influence of Charging Equipment Brand

............................................................................................................................30

How Do Customers Interact With Charging Equipment?

....................................................................................................32

EV Consumers’ Willingness to Pay for Charging Services and the Influence of Price

in This Perception

................................................................................................................................................................................32

EV Consumers’ Perception of Various Billing Methods

............................................................................................34

EV Consumers’ Comfort With the Various Payment Options

..............................................................................36

What Do Customers Do at Facilities While Charging?

........................................................................................................38

Dwell Time at Public Chargers and the Features That Could Influence That Dwell Time

................38

Features and Amenities That Are Most Desired by EV Drivers, Used During a Charging

Session, and That Could Influence Drivers to Use Charging Stations Frequently

................................41

Features and Amenities That Yield the Greatest Influence Over an EV Driver’s

Decision Regarding Where to Charge

................................................................................................................................42

Contents

FUELS INSTITUTE | EVC | EV CONSUMER BEHAVIOR

5

PERSONA FINDINGS ......................................................................................................................................................... 45

Michael: Affluent Middle-aged White Male With BEV As Secondary Vehicle Living in the

California Bay Area With Access to At-home Charging

.....................................................................................................44

Shou: Affluent, Middle-aged Asian American Male With BEV As Secondary Vehicle Living

With At-home Charger Who Frequents a Metropolitan City

............................................................................................ 46

Raj: Middle-class Young Male of Indian Heritage With BEV As Primary Vehicle for a 20-mile

Commute Who Lives in an Apartment Building With Shared Chargers

..................................................................48

Millicent: Elderly Environmentally Conscious Female on a Fixed Income With a BEV As a

Primary Vehicle With an At-home Charger

...................................................................................................................................50

Amy: Businesswoman Who Drives a Work Truck and Could Potentially Buy an Electric Truck

........... 52

CONCLUSIONS

.........................................................................................................................................................................54

APPENDIX

......................................................................................................................................................................................55

Acronyms and Abbreviations

................................................................................................................................................................... 56

Bibliography

.........................................................................................................................................................................................................57

FUELS INSTITUTE | EVC | EV CONSUMER BEHAVIOR

6

INTRODUCTION

The Fuels Institute commissioned Ricardo Strategic

Consulting (“Ricardo”) to review existing literature

to better understand how consumers drive, where

they recharge their EVs, and what they would like

to experience during a recharging occasion in terms

of site design, amenities, capabilities, and services.

In addition to this, the study seeks to understand

consumer behavior today and anticipate how

it might evolve over the next 10 years as more

consumers purchase EVs.

Fuels Institute is a not-for-profit organization

led by a collaborative group of fuel retailers, fuel

producers and refiners, alternative and renewable

fuels producers, automobile manufacturers, and

others with expertise in the fuels and automotive

industries. The Institute delivers comprehensive

and balanced research and analysis concerning

fuels, vehicles, and related policy issues. The Electric

Vehicle Council is a project of the Fuels Institute

comprised of organizations seeking to eliminate

confusion and provide guidance for success

relative to the installation and operation of retail EV

charging stations through stakeholder collaboration,

objective research, and market education. Ricardo

has aligned its research and opinions in this report

to a similar unbiased philosophy.

LITERATURE STUDY CONTEXT

The market for EVs is expanding, and there is

significant need for charging infrastructure. To

ensure that the infrastructure satisfies the needs

and interests of EV drivers and site hosts alike, it is

important to understand what those drivers want

and how they would use the infrastructure. This

information would be particularly useful to charger

operators to help design appropriate facilities.

Furthermore, as the EV market grows, the

demographic profile of the EV driver is likely to

change and become more diverse. The diversity

of future EV drivers could require dierent designs

and amenities to support the various demands of

the consumers. Given that charging systems will

be long-lived assets that could be in use 10 years or

longer following installation, it is essential to better

anticipate how drivers will use these systems to

ensure the designs remain relevant to driver needs

throughout their expected useful life. This literature

review is intended to identify trends in EV consumer

behavior today, how it has evolved over the past 10

years, and how it could evolve in the next few years

to align with the goal of anticipating how drivers will

use these systems over the life of the systems.

Ricardo has found that most of the existing research

on EV charging preferences is conducted with

current EV owners and potential buyers. These

owners are likely to use, or work around, the existing

infrastructure even with sub-optimal charging

speed, density, or site design. Identifying charging

preferences of the buyer who is not yet considering

EV purchase will be equally important to future

infrastructure. This report cites existing literature.

FUELS INSTITUTE | EVC | EV CONSUMER BEHAVIOR

7

OBJECTIVE OF THE STUDY

In order to understand consumer behavior today, in

the past 10 years, and expected trends over the

next

10 years, this report has been structured to answer

the

following broad questions and their sub-questions:

Who is the customer?

• What is the demographic profile of today’s EV

drivers? How does this compare to the population

at large, how has it evolved over the past 10 years,

and how might it evolve over the next 10 years?

• Which demographic characteristics most

influence EV ownership and behavior?

• How do trips taken in an EV dier, if at all, from

those taken in a liquid-fueled vehicle?

When and where does the customer recharge?

• With what frequency do EV drivers recharge their

vehicles? Where do consumers recharge their

vehicles? What are the factors that influence

drivers to initiate a recharging occasion? How

does this behavior compare with drivers of

liquid-fueled vehicles?

• How oen do EV drivers charge at public stations?

Why do they choose to charge at a public station

versus at home, work, or other locations? What

would encourage them to use public charging

stations more frequently?

• How much charging infrastructure will be

required to service demand compared to the

amount of charging infrastructure required

to provide consumers with suicient comfort

regarding convenient accessibility of chargers?

Why does the customer choose a particular public

recharging facility?

• To what extent does the availability of Level 2

charging influence consumer perception about

charging availability, capacity, and convenience

compared with DCFC equipment? How would the

price of the service influence this perception?

• Is there a dierence in consumer perception

relative to the identity type of the charging

station host, e.g., a restaurant, convenience store,

shopping center, grocery store, parking garage,

public verses private entity?

• To what extent does the brand of the charger

equipment influence selection?

• How oen do consumers use apps to find

appropriate public charging, and will the use of

these apps grow or diminish as EVSE becomes

more available?

How do customers interact with charging

equipment?

• How willing are consumers to pay for

charging services?

• How do they perceive various billing methods?

• How comfortable are they with various

payment options?

• Do their perceptions change depending on

the identity of the company initiating the

transaction?

What do customers do at facilities while charging?

• How much time do drivers expect to spend at a

charging station, and what facility features would

influence that expected dwell time?

• Which facility features and amenities are most

desired by EV drivers and used during a charging

occasion? How does this change with variations

in dwell time? Which features or amenities yield

the greatest influence over an EV driver’s decision

regarding where to charge?

• Do EV drivers use facility amenities more or less

frequently than other customers at the facility?

• How much money do EV drivers spend at these

facilities compared with other drivers?

FUELS INSTITUTE | EVC | EV CONSUMER BEHAVIOR

8

PERSONAS

Personas are created to exemplify predicted individual preferences by conducting internal interviews.

Five personas and their daily habits are outlined below. These have been picked to represent various

demographics, their use cases, and perceptions of EV ownership and charging. Ricardo formed teams of

4-5 individuals to discuss each persona. This structure helps describe individual character choices with

regards to their daily habits and preferences. A short outline of these personas is mentioned below.

Details will be found towards the end of the report.

Michael represents the top demographic of today’s EV buyer: an

aluent, white, 37-year-old man living in the California Bay Area

with the EV as a second vehicle. Michael’s character is chosen to

demonstrate the behavior of a large section of today’s EV owners.

Shou is a 49-year-old Asian American man who also owns an

EV as a secondary vehicle. His travel needs are limited, and he

prefers public transport to driving. Shou’s character serves to help

understand the benefit of owning an EV when car travel is limited.

Raj is a 28-year-old electrical engineer of Indian origin who lives

in an apartment with a common, shared EV charging station. Raj

is much younger than the average age of EV owners, and the EV is

his only car.

Millicent is a 68-year-old African American woman who lives on

a fixed income and owns an EV as her primary vehicle. Millicent’s

character brings to light the reasoning to own an EV as a means to

show her devotion to the eco-conscious ideology. She is one of the

rare examples who does not use fast chargers and charges at home

on a Level 1 charger.

Amy is a 43-year-old white woman who owns her

electrician business and is a prospective buyer of an electric

pickup truck. The total cost of operation of an electric truck

is attractive given her high daily mileage. Her character helps

understand the requirements that need to be met in order to

cater to the prospective buyer that finds the current EV

infrastructure unsatisfactory.

FUELS INSTITUTE | EVC | EV CONSUMER BEHAVIOR

9

METHODOLOGY

In compiling this report, Ricardo has researched

the following:

1. Public domain resources, including

published surveys; federal, state, and local

government publications; cross-functional

organization publication; scholarly articles;

university/institute publications; national lab

publications; public policies; and

press reports

2. Existing Ricardo studies on user preferences

for future mobility (e.g., Ricardo’s ongoing

engagement with the California Air

Resources Board)

1

3. Supplemental persona creation to exemplify

individual preferences

Throughout the report, the terms PEV, BEV, and EV

are used frequently. A PEV within this report refers

to a combination of both plug-in hybrid electric

vehicles (PHEVs) and BEVs. The term PEV is primarily

used when the study particularly involves both

PHEVs and BEVs. The terms BEV and EV are used

interchangeably when referring to BEVs.

The term PHEV, in this report, refers to vehicles that

use batteries to power an electric motor and use

another fuel, such as gasoline, to power an ICE. BEVs

or EVs are defined, within this report, as vehicles that

have an electric motor instead of an ICE.

1 Ricardo, “Ricardo awarded key heavy-duty zero-emissions vehicle project by CARB,” news release, October 24, 2021, https://ricardo.com/news-and-media/news-and-

press/ricardo-awarded-key-heavy-duty-zero-emissions-vehi.

2 “AVTA: The EV Project,” Oice of Energy Eiciency and Renewable Energy, U.S. Department of Energy, https://www.energy.gov/eere/vehicles/avta-ev-project.

The EV Project mentioned in this report refers to the

study conducted by the Idaho National Laboratory

(INL) in partnership with Electric Transportation

Engineering Corporation, Nissan, General Motors,

and more than 10,000 other city, regional, and state

governments, electric utilities, other organizations,

and members of the public.

2

They deployed over

12,000 AC Level 2 (208-240V) charging units and

over 100 dual-port DCFC in 20 metropolitan areas.

Approximately 8,300 Nissan Leafs, Chevrolet Volts,

and smart EQ fortwo vehicles were driven over 125

million miles, and charging-related data for over

4 million charging events was captured between

January 1, 2011, and December 31, 2013. This was

the largest deployment and evaluation project of EVs

and charging infrastructure.

FUELS INSTITUTE | EVC | EV CONSUMER BEHAVIOR

10

PROJECT REPORT

WHO IS THE CUSTOMER?

DEMOGRAPHICS

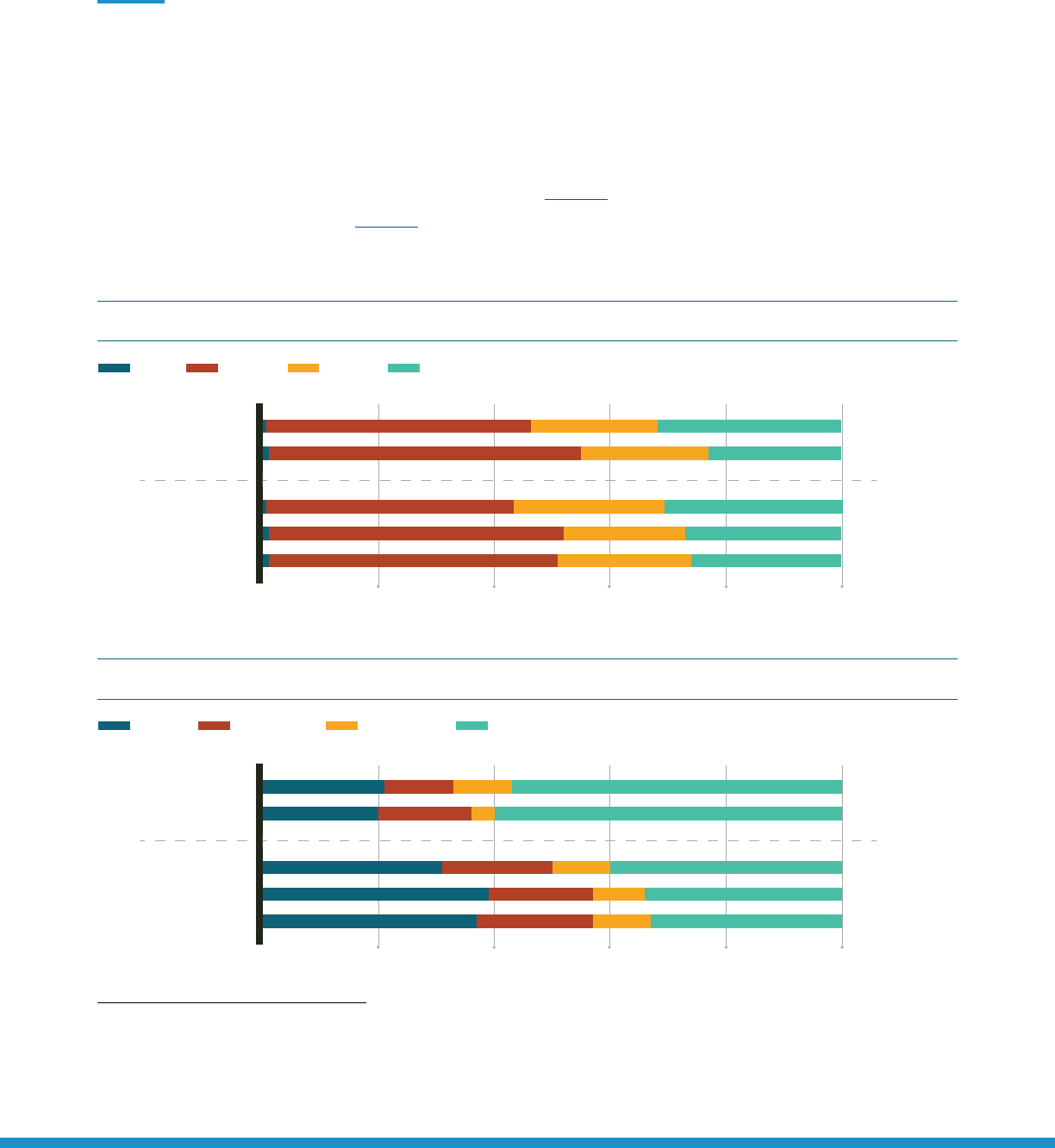

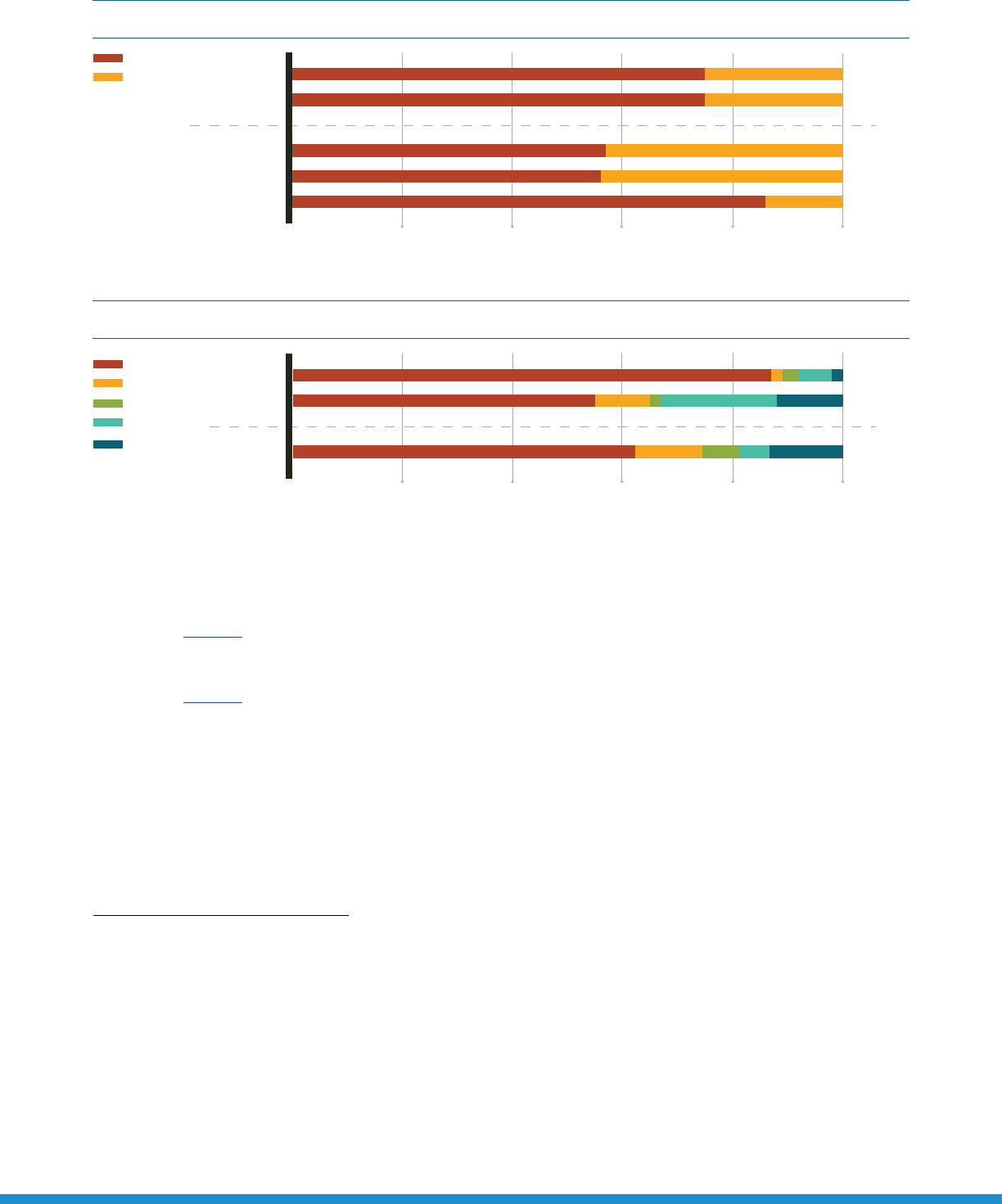

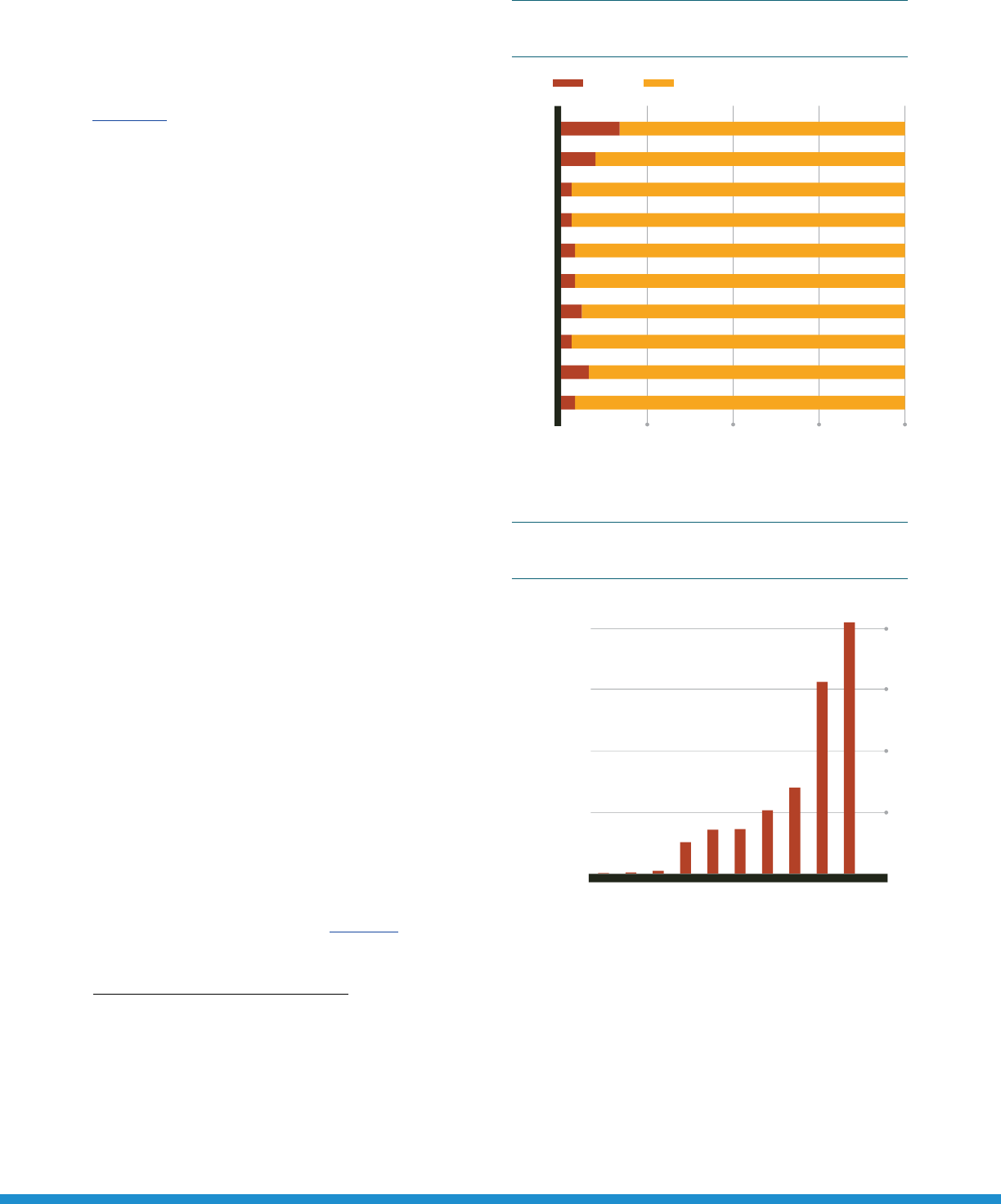

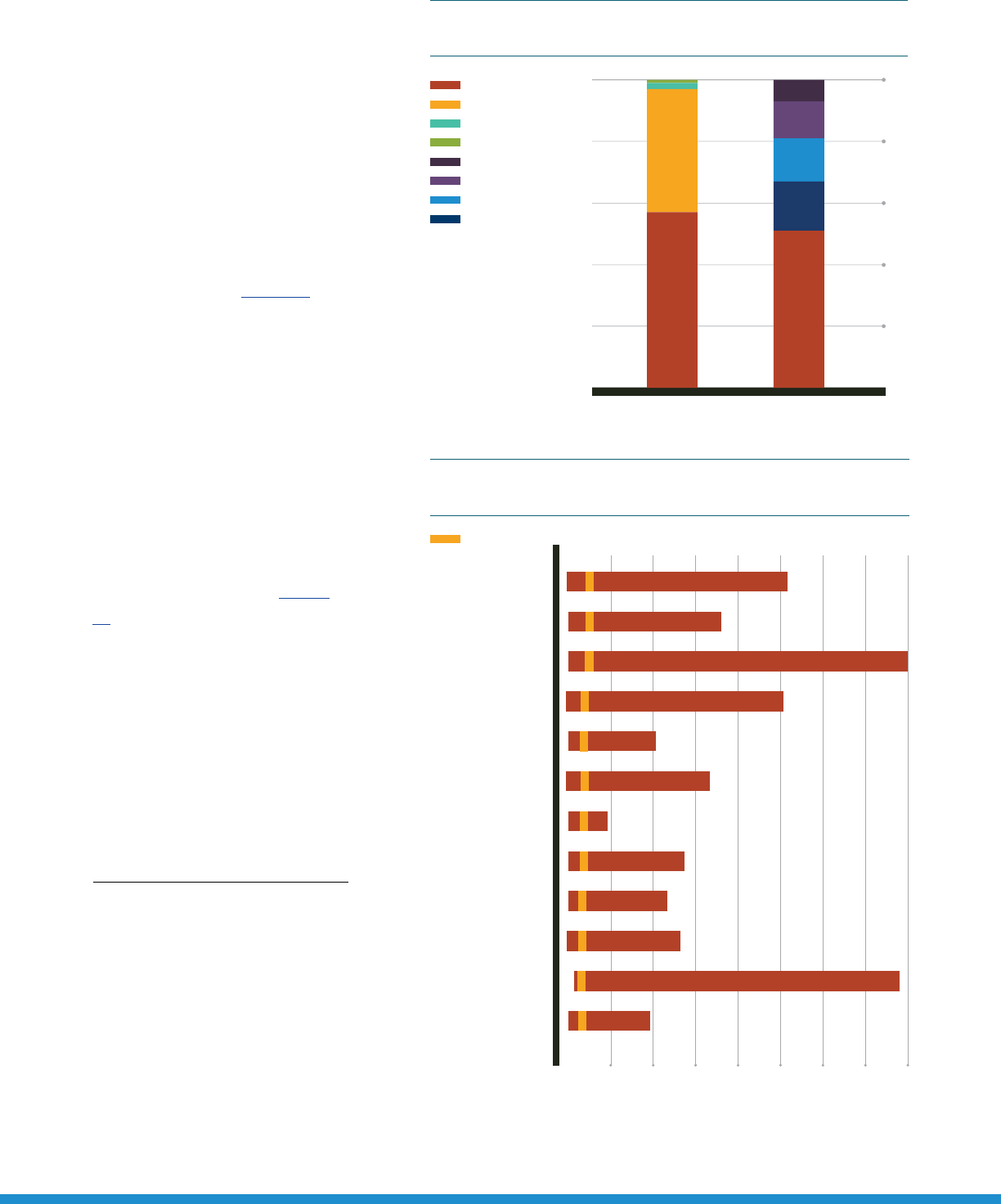

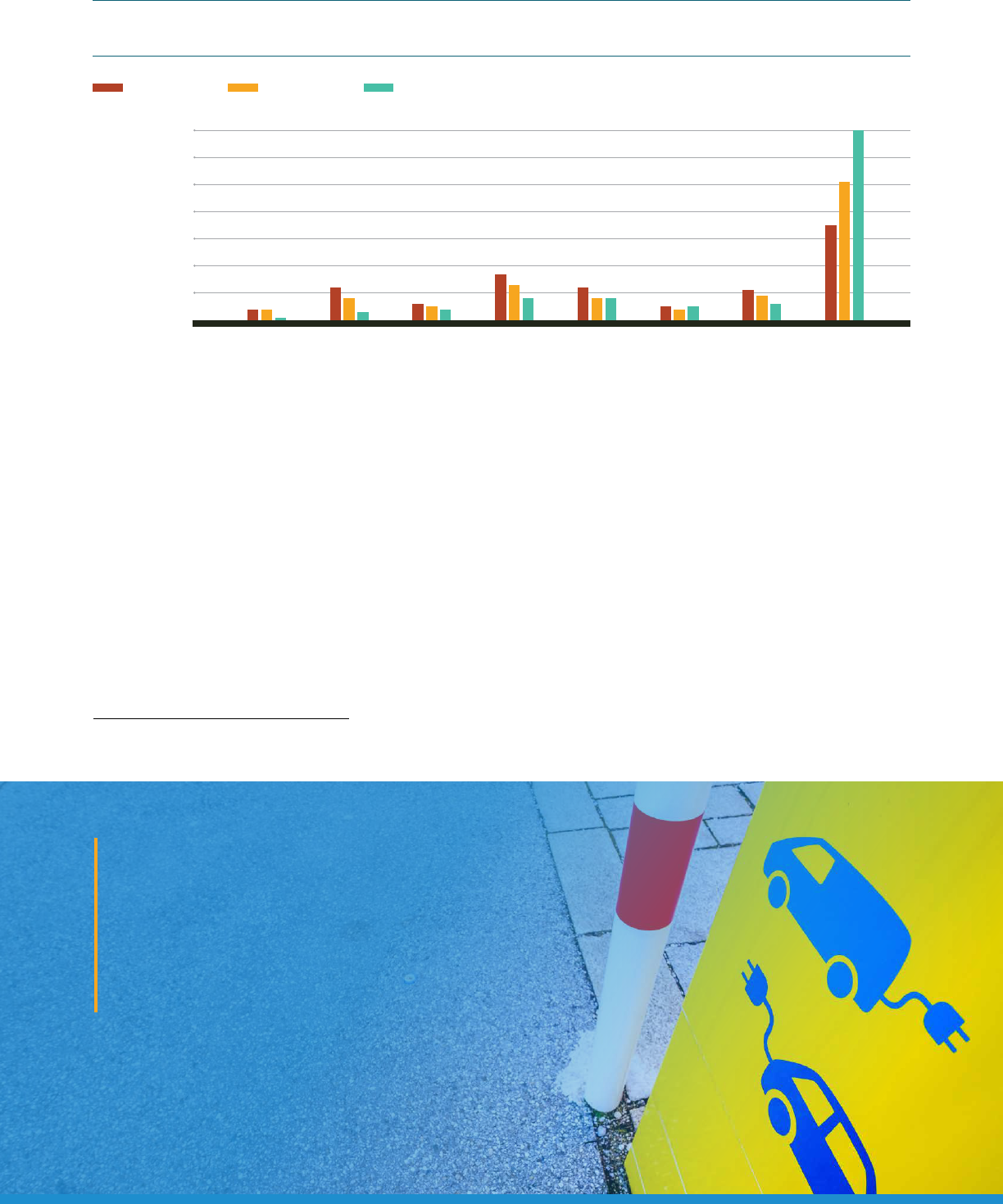

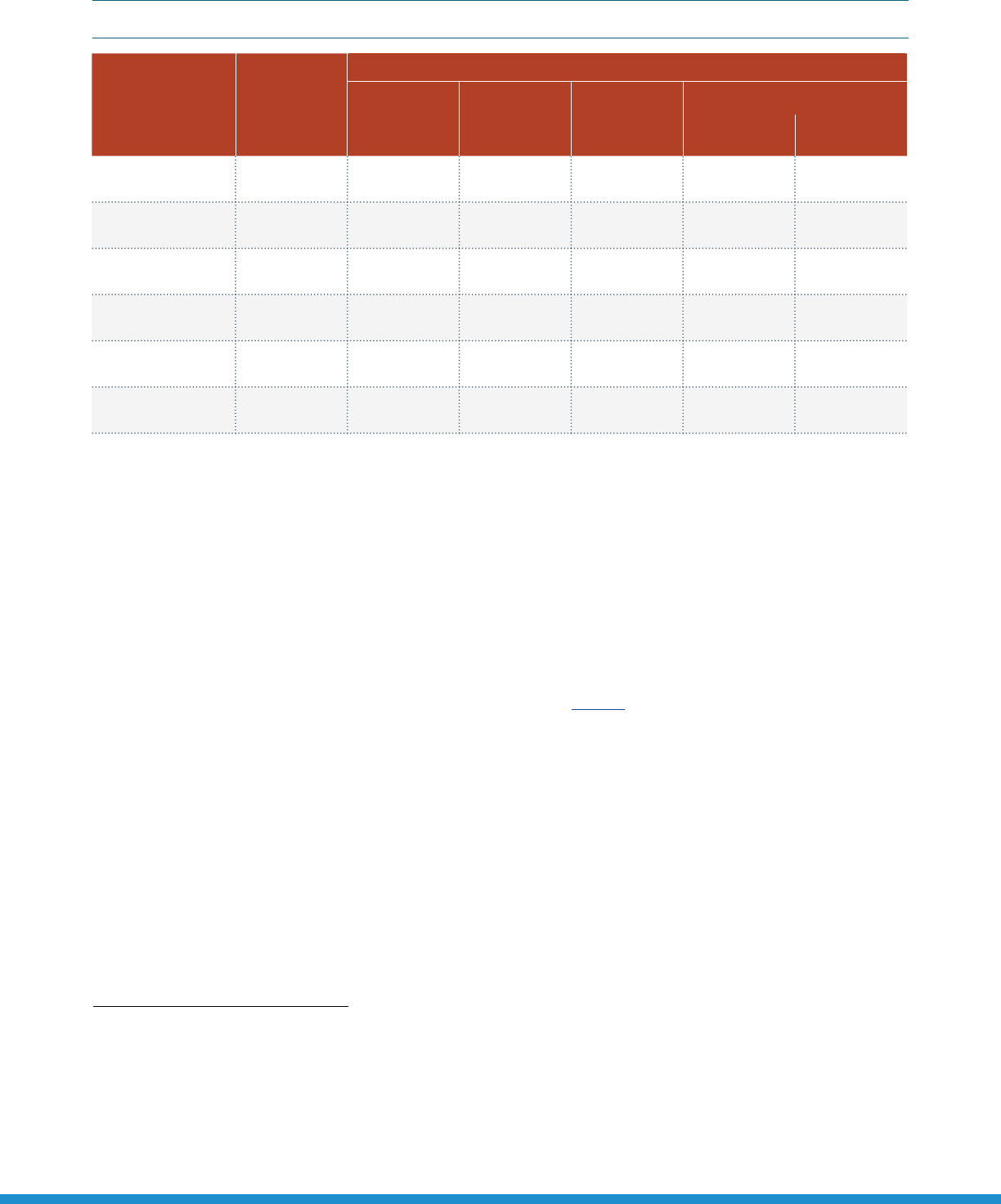

PEV buyers tend to follow the general trend of new

car buyers. The dominant age group for PEV buyers

across the board is 25-54 years old, according to

Hedges Company’s 2019 survey (Figure 1).

3

3 “New Car Buyer Demographics 2020 (Updated),” Hedges & Company, accessed October 5, 2020, https://hedgescompany.com/blog/2019/01/new-car-buyer-

demographics-2019/.

4 “New Car Buyer Demographics 2020 (Updated)”

5 Christopher Butler, “Electric Vehicle Prices Finally in Reach of Millennial, Gen Z Car Buyers,” CNBC, October 20, 2019, updated: October 21,2019, https://www.cnbc.

com/2019/10/20/electric-car-prices-finally-in-reach-of-millennial-gen-z-buyers.html.

The most dominant annual household income

bracket amongst PEV buyers is “greater than

$100,000.” For conventional vehicles, buyers are

almost evenly split between “less than $50,000” and

“greater than $100,000” annual household income

(Figure 2).

4

The average household annual income

of most EV owners is found to be between $125,000

and $150,000, according to the same survey.

5

<24 25-54 55-64 >65

<$50k $50k-$75k $75k-$99k >$100k

United Sates

of America

SUV

PHEV

BEV

Sedan

Trucks

Conventional

Conventional

Electric

New Car Buyers

Country Population

United Sates of America 2,677

Brazil 5,461

Mexico 10,560

Argentina 11,242

4000

6000

1% 54% 22% 23%

1% 51% 21% 27%

1% 50% 23% 26%

0.60% 42.80% 25.80% 30.80%

0.60% 45.80% 21.80% 31.80%

0.6% 44.8% 21.8% 31.8%

0.6% 42.8% 25.8% 30.8%

2,677

5,461

10,560

11,242

7,731,952

29.2 32.8 35.8 39.4 41.4 39.9 41.2 41.3

2,677

United Sates

of America

SUV

PHEV

BEV

Sedan

Trucks

Conventional

Conventional

Electric

New Car Buyers

Country Population

United Sates of America 2,677

Brazil 5,461

Mexico 10,560

Argentina 11,242

4000

6000

21% 12% 10% 57%

20% 16% 4% 60%

31% 19% 10% 40%

39% 18% 9% 34%

37% 20% 10% 33%

2,677

5,461

10,560

11,242

7,731,952

29.2 32.8 35.8 39.4 41.4 39.9 41.2 41.3

2,677

FIGURE 1: SPLIT OF NEW CAR BUYERS BASED ON AGE GROUP (2019)

FIGURE 2: SPLIT OF NEW CAR BUYERS BASED ON ANNUAL HOUSEHOLD INCOME BRACKET (2019)

Source: “New Car Buyer Demographics 2020 (Updated),” Hedges & Company (rounded numbers used in some cases)

Source: “New Car Buyer Demographics 2020 (Updated),” Hedges & Company

FUELS INSTITUTE | EVC | EV CONSUMER BEHAVIOR

11

United Sates

of America

Overall

CA

USA

Conventional

New Car Buyers

Country Population

United Sates of America 2,677

Brazil 5,461

Mexico 10,560

Argentina 11,242

4000

6000

87% 6%

2% 3%

2%

2%

21%10%55% 12%

62% 12% 7% 6% 13%

56% 44%

86% 14%

On-Road

Residential

O-Road

Commercial

Industrial

Farming

Petroleum

Elictric Utility

Railroad

Shipping

2,677

5,461

10,560

11,242

7,731,952

29.2 32.8 35.8 39.4 41.4 39.9 41.2 41.3

2,677

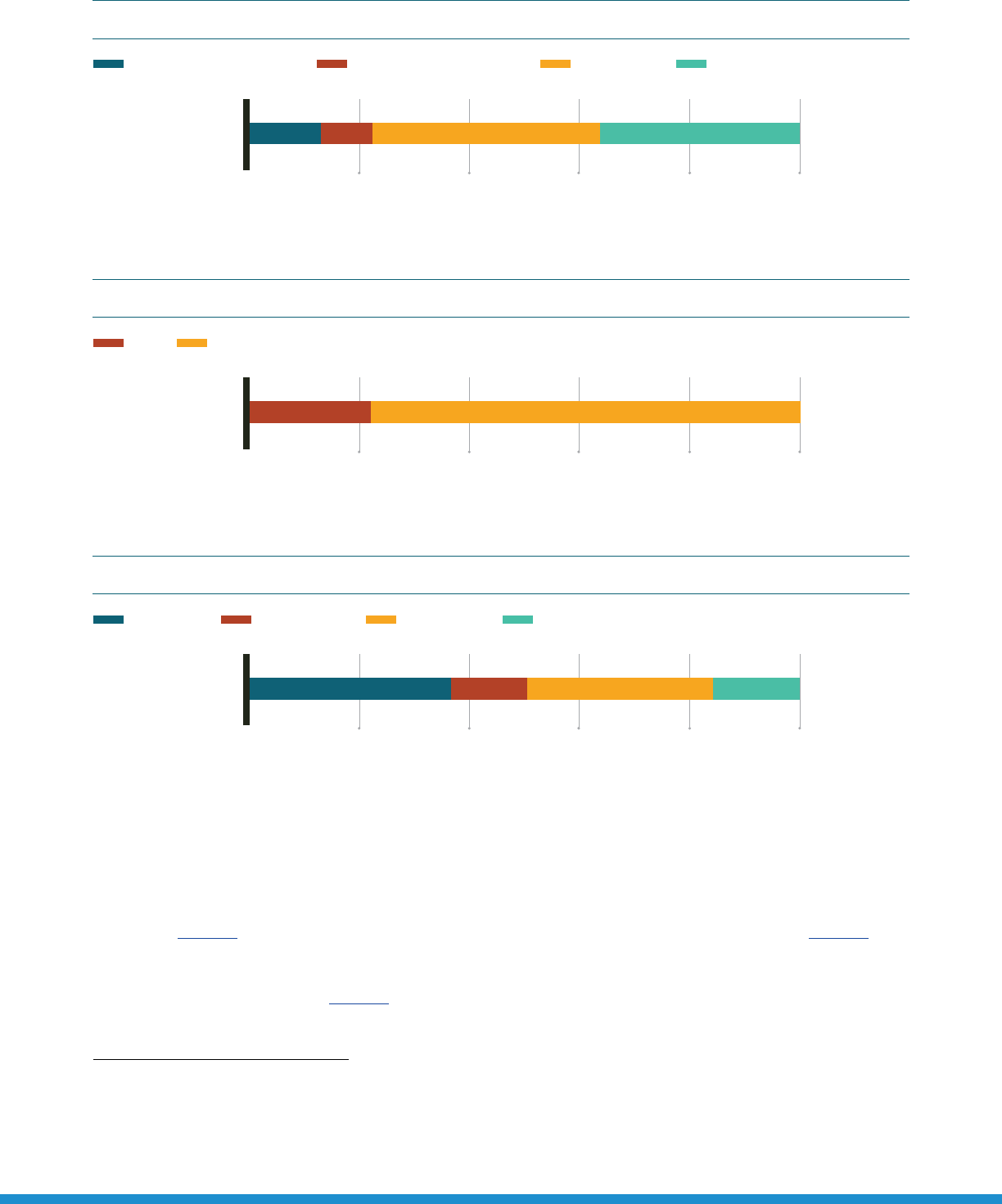

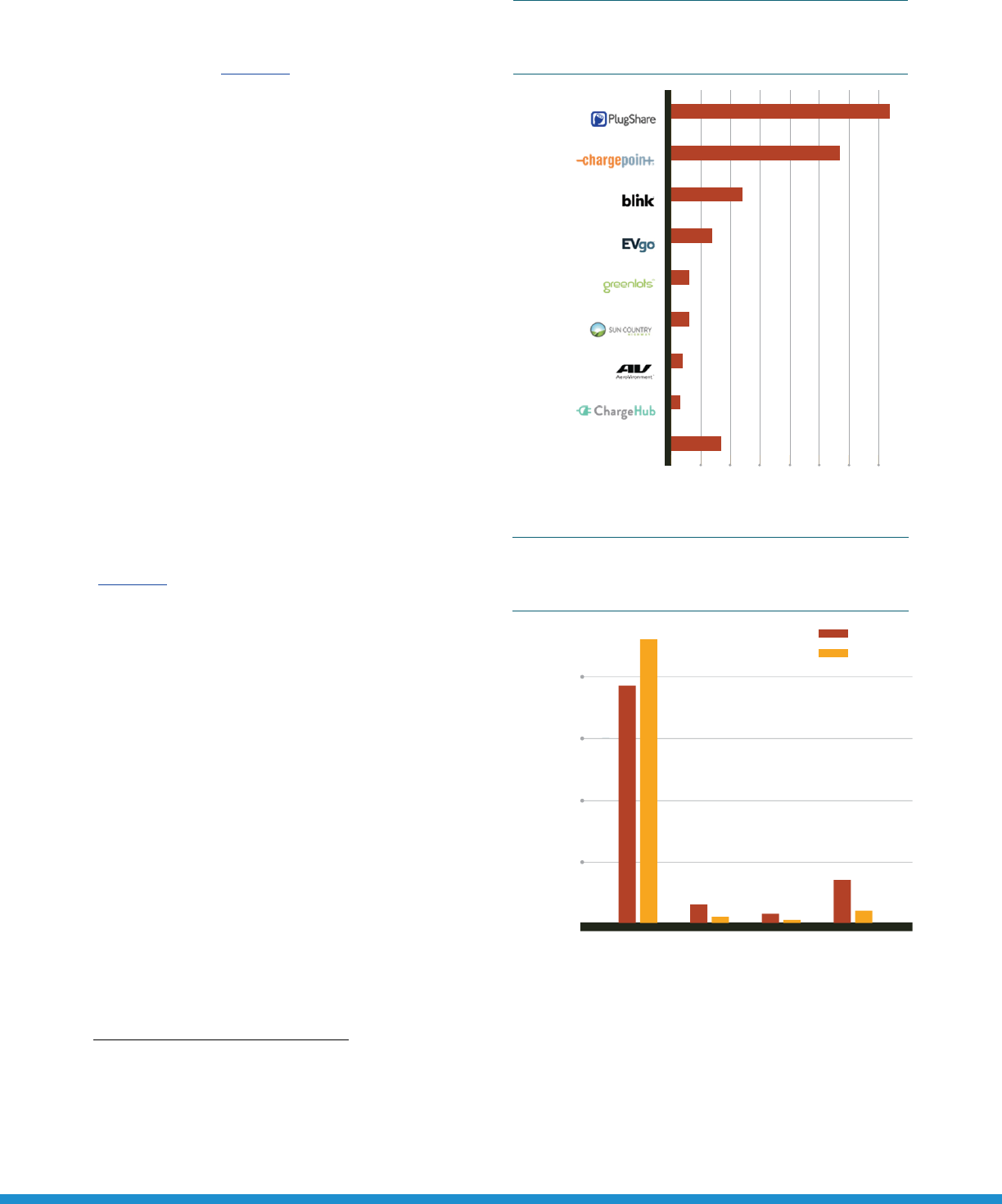

As shown in Figure 3,

6

PEV buyers, similar to conventional-fuel truck buyers, are mostly male.

7

Sport utility

vehicles (SUV) and sedans have a more balanced distribution amongst male and female buyers.

8

As shown in Figure 4,

9

PEV buyers nationally in the U.S. are mostly white (87%) according to a study conducted

by Morgan State University.

10

The distribution of the white population is slightly elevated in comparison to the

distribution of the U.S. population, with 75% white, 13% Black or African American, 6% Asian, and 6% others.

11

Black or African American ethnicity, however, appears to be underrepresented amongst EV buyers. However, in

California, according to a survey conducted by the University of California, Davis, and the National Center for

Sustainable Transportation, while the distribution of buyers also is mostly white, Asian American PEV buyers

appear to closely follow at 21%. This can also be attributed to the fact that California is one of the states with a

higher population density of Asian Americans.

12

6 “New Car Buyer Demographics 2020 (Updated)”; Z. Andrew Farkas, Hyeon-Shic Shin, Seyedehsan Dadvar, and Jessica Molina, Electric Vehicle Ownership Factors,

Preferred Safety Technologies, and Commuting Behavior in the United States (Charlottesville, VA: Mid-Atlantic Transportation Sustainability University Transportation

Center, University of Virginia, February 2017), available at http://www.matsutc.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Environmental-and-Safety-Attributes-of-Electric-Vehicle-

Ownership-and-Commuting-Behavior-Public-Policy-and-Equity-Consideration.pdf.

7 “New Car Buyer Demographics 2020 (Updated)”

8

“New Car Buyer Demographics 2020 (Updated)”; Farkas et al., Electric Vehicle Ownership Factors, Preferred Safety Technologies, and Commuting Behavior in the United States

9 Farkas et al., Electric Vehicle Ownership Factors, Preferred Safety Technologies, and Commuting Behavior in the United States; Erich Muehlegger and David Rapson,

Impacts of Vehicle Policy: Who Buys New and Used Alternative Vehicles?, prepared by Morgan State University (National Center for Sustainable Transportation, University of

California Davis, February 2018), available at https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0tn4m2tx; Statista Research Department, Structure of New Vehicle Buyers in the United States,

Distributed by Ethnicity Between January and May of 2014 and 2015, May 2016, accessed October 20, 2020, https://www.statista.com/statistics/549852/structure-of-new-

vehicle-buyers-united-states-by-ethnicity/.

10 Farkas et al., Electric Vehicle Ownership Factors, Preferred Safety Technologies, and Commuting Behavior in the United States

11 “2019: ACS 1-Year Estimates Detailed Tables” (Table ID C02003, Universe: Total Population, Survey/Program: American Community Survey), United States Census Bureau,

accessed October 29, 2020, available at https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=race&g=0100000US.04000.001&tid=ACSDT1Y2019.C02003&moe=false&tp=true&hidePreview=true.

12 “2019: ACS 1-Year Estimates Detailed Tables”

Male

Female

United Sates

of America

SUV

PHEV

BEV

Sedan

Trucks

Conventional

Conventional

Electric

New Car Buyers

Country Population

United Sates of America 2,677

Brazil 5,461

Mexico 10,560

Argentina 11,242

4000

6000

75% 25%

75% 25%

57% 43%

56% 44%

86% 14%

On-Road

Residential

O-Road

Commercial

Industrial

Farming

Petroleum

Elictric Utility

Railroad

Shipping

2,677

5,461

10,560

11,242

7,731,952

29.2 32.8 35.8 39.4 41.4 39.9 41.2 41.3

2,677

FIGURE 3: SPLIT OF NEW CAR BUYERS BASED ON GENDER (2019)

Sources: “New Car Buyer Demographics 2020 (Updated),” Hedges & Company; Farkas et al., Electric Vehicle Ownership Factors, Preferred Safety

Technologies, and Commuting Behavior in the United States

White

Hispanic

Black

Asian

FIGURE 4: SPLIT OF PEV BUYERS BASED ON ETHNICITY (USA 2014, CA 2018, OVERALL 2015)

Note: U.S. sample population is 379 EV owners

Sources: Farkas et al., Electric Vehicle Ownership Factors, Preferred Safety Technologies, and Commuting Behavior in the United States;

Erich Muehlegger and David Rapson, Impacts of Vehicle Policy: Who Buys New and Used Alternative Vehicles?; Statista Research Department,

Structure of New Vehicle Buyers in the United States, Distributed by Ethnicity Between January and May of 2014 and 2015

Other

FUELS INSTITUTE | EVC | EV CONSUMER BEHAVIOR

12

Democrat

1

Most PEV owners have at least a four-year degree

according to the survey conducted by Morgan State

University (Figure 5).

13

AAA’s survey of EV owners revealed that 78% of them

also owned a gas-powered car (Figure 6).

14

13 Farkas et al., Electric Vehicle Ownership Factors, Preferred Safety Technologies, and Commuting Behavior in the United States

14 Ellen Edmonds, “AAA: Owning an Electric Vehicle is the Cure for Most Consumer Concerns,” AAA, January 22, 2020, https://newsroom.aaa.com/2020/01/aaa-owning-

anelectric-vehicle-is-the-cure-for-most-consumer-concerns/.

15 Farkas et al., Electric Vehicle Ownership Factors, Preferred Safety Technologies, and Commuting Behavior in the United States

In a survey conducted by Morgan State University in

2017, it was observed that slightly more Democrats

owned PEVs compared to Republicans (Figure 7).

15

Some college/2-year degree

Independent

More than or equal to 2

4-year degree

Republican

Graduate degree

Unailiated

United Sates

of America

PEV owners

SUV

PHEV

BEV

Sedan

Trucks

Conventional Electric

New Car Buyers

New Car Buyers

Country Population

United Sates of America 2,677

Brazil 5,461

Mexico 10,560

Argentina 11,242

4000

6000

21% 12% 10% 57%

20% 16% 4% 60%

31% 19% 10% 40%

39% 18% 9% 34%

37%

13% 10% 41% 36%

20% 10% 33%

2,677

5,461

10,560

11,242

2,677

5,461

10,560

11,242

7,731,952

29.2 32.8 35.8 39.4 41.4 39.9 41.2 41.3

2,677

United Sates

of America

PEV owners

SUV

PHEV

BEV

Sedan

Trucks

Conventional Electric

New Car Buyers

Country Population

United Sates of America 2,677

Brazil 5,461

Mexico 10,560

Argentina 11,242

4000

6000

21% 12% 10% 57%

20% 16% 4% 60%

31% 19% 10% 40%

39% 18% 9% 34%

37%

37% 14% 34% 16%

20% 10% 33%

2,677

5,461

10,560

11,242

2,677

5,461

10,560

11,242

7,731,952

29.2 32.8 35.8 39.4 41.4 39.9 41.2 41.3

2,677

United Sates

of America

PEV owners

SUV

PHEV

BEV

Sedan

Trucks

Conventional Electric

New Car Buyers

New Car Buyers

Country Population

United Sates of America 2,677

Brazil 5,461

Mexico 10,560

Argentina 11,242

4000

6000

21% 12% 10% 57%

20% 16% 4% 60%

31% 19% 10% 40%

39% 18% 9% 34%

37%

22% 78%

20% 10% 33%

2,677

5,461

10,560

11,242

2,677

5,461

10,560

11,242

7,731,952

29.2 32.8 35.8 39.4 41.4 39.9 41.2 41.3

2,677

FIGURE 5: SPLIT OF PEV OWNERS BASED ON EDUCATION LEVEL (2017)

FIGURE 7: POLITICAL AFFILIATION OF PEV OWNERS (2017)

FIGURE 6: SPLIT OF PEV OWNERS BASED ON NUMBER OF VEHICLES IN HOUSEHOLD (2020)

Some high school/diploma

Source: Farkas et al., Electric Vehicle Ownership Factors, Preferred Safety Technologies, and Commuting Behavior in the United States

Source: Ellen Edmonds, “AAA: Owning an Electric Vehicle is the Cure for Most Consumer Concerns”

Source: Farkas et al., Electric Vehicle Ownership Factors, Preferred Safety Technologies, and Commuting Behavior in the United States

FUELS INSTITUTE | EVC | EV CONSUMER BEHAVIOR

13

In a study conducted by Climate Nexus, Democrats viewed EVs slightly more favorably than Republicans

(Figure 8).

16

When asked about the likeliness to consider purchasing or leasing an EV next time, approximately

53% Democrats and approximately 35% Republicans responded airmatively. When asked if they would

consider buying or leasing an EV if they were oered a guaranteed $7,500 tax rebate, their responses changed

dramatically: 78% Democrats and 71% Republicans said they are likely to consider one.

16 “National Poll Results,” Climate Nexus, 2015, https://climatenexus.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/EV-Poll-Results.pdf.

United Sates

of America

Conventional

SUV

PHEV

BEV

Sedan

Trucks

Conventional Electric

New Car Buyers

Positive/negative

opinion about EVs

Likeliness to consider an

EV next time they buy/lease

Likeliness to consider an

EV if given a guaranteed

$7,500 tax rebate

Democrats 26.75% 56.75% 13.75% 2.75%

Independent 18.00% 57.00% 20.00% 5.00%

Republican 16.00% 54.00% 24.00% 6.00%

Others 17.75% 54.75% 21.75% 5.75%

Democrats 16.25% 37.25% 26.25% 20.25%

Independent 9.75% 32.75% 33.75% 23.75%

Republican 8.00% 27.00% 33.00% 32.00%

Others 17.00% 38.00% 28.00% 17.00%

48.20% 30.20% 4.20% 1.20% 16.20%

35.00% 36.00% 4.00% 2.00% 23.00%

37.00% 34.00% 4.00% 3.00% 22.00%

37.00% 31.00% 8.00% 2.00% 22.00%

4000

26.75% 56.75% 13.75%

20%

21% 12% 10% 57%

20% 16% 4% 60%

31% 19% 10% 40%

39% 18% 9% 34%

37% 20% 10% 33%

Democrats

Independent

Republican

Others

2.75%

18% 57% 20%

5%

16% 54% 24%

6%

17.75% 54.75% 21.75%

5.75%

16.25%

26.25%

37.25%

20.25%

20%

10% 34% 24%

8% 33% 32%

17% 28%

33%

27%

38% 17%

48.2% 30.2% 16.2%

20%

1.2%

35% 36% 23%

2%

37% 34% 22%

3%

37% 37% 22%

2%

4.2%

4%

4%

8%

2,677

5,461

10,560

11,242

29.2 32.8 35.8 39.4 41.4 39.9 41.2 41.3

2,677

FIGURE 8: VIEWS ON EVS GROUPED BY POLITICAL AFFILIATION (2019)

Very positive

Somewhat negative

Somewhat positive

Very negative

Verylikely

Somewhat unlikely

Somewhat likely

Very unlikely

Much more likely

No dierence

Somewhat less likely

Somewhat more likely

Much less likely

FUELS INSTITUTE | EVC | EV CONSUMER BEHAVIOR

Source: “National Poll Results,” Climate Nexus (rounded numbers used in some cases)

FUELS INSTITUTE | EVC | EV CONSUMER BEHAVIOR

14

DRAFT

20

Note: Total registrations in California is 256,000 but the legend ends at 30,000 to highlight the variation in other states.

Distribution of BEVs is concentrated along the ZEV (zero-emission vehicle) belt.

18

BEV

registrations in California in 2018 were approximately 256,000, which was roughly equal to the

BEV registrations in all other states combined (approximately 286,000).

19

This distribution appears

to correspond with individual income in each state (Figure 10) and the EV policies and incentives

in each state (Figure 11). When compared to the overall number of vehicles registered by state,

EVs constitute a very small percentage (Figure 12).

20

FIGURE 10: INDIVIDUAL INCOME BY STATE (2018)

21

18

“Electric Vehicle Registrations by State”

19

“Electric Vehicle Registrations by State”

20

“Electric Vehicle Registrations by State”; U.S. Automobile Registrations in 2018, by State”

21

“SOI Tax Stats — Individual Income Tax Statistics — 2018 ZIP Code Data (SOI),” Internal Revenue Service,

2018, accessed October 20, 2020, available at https://www.irs.gov/statistics/soi-tax-stats-individual-income-tax-

statistics-2018-zip-code-data-soi.

FIGURE 10: INDIVIDUAL INCOME BY STATE (2018)

DRAFT

21

Note: Darker color indicates a larger sum of individual income.

FIGURE 11: EV LAWS AND INCENTIVES (2020)

22

Note: Darker color indicates a greater number of laws and incentives; California leads at 104.

FIGURE 12: SPLIT OF VEHICLE REGISTRATIONS BY STATE (TOP 10) (2018)

23

22

“Electric Vehicle Laws and Incentives by State” (chart), “Maps and Data — Electric Vehicle Laws and Incentives

by State” (webpage), Alternative Fuels Data Center, Alternate Fuels Data Center, Office of Energy Efficiency &

Renewable Energy, U.S. Department of Energy, accessed October 22, 2020, available at

https://afdc.energy.gov/data/10373.

23

“U.S. Automobile Registrations in 2018, by State,” Statista, March 2021,

https://www.statista.com/statistics/196010/total-number-of-registered-automobiles-in-the-us-by-state/; “Electric

Vehicle Registrations by State”

FIGURE 11: EV LAWS AND INCENTIVES (2020)

DRAFT

21

Note: Darker color indicates a larger sum of individual income.

FIGURE 11: EV LAWS AND INCENTIVES (2020)

22

Note: Darker color indicates a greater number of laws and incentives; California leads at 104.

FIGURE 12: SPLIT OF VEHICLE REGISTRATIONS BY STATE (TOP 10) (2018)

23

22

“Electric Vehicle Laws and Incentives by State” (chart), “Maps and Data — Electric Vehicle Laws and Incentives

by State” (webpage), Alternative Fuels Data Center, Alternate Fuels Data Center, Office of Energy Efficiency &

Renewable Energy, U.S. Department of Energy, accessed October 22, 2020, available at

https://afdc.energy.gov/data/10373.

23

“U.S. Automobile Registrations in 2018, by State,” Statista, March 2021,

https://www.statista.com/statistics/196010/total-number-of-registered-automobiles-in-the-us-by-state/; “Electric

Vehicle Registrations by State”

DRAFT

21

Note: Darker color indicates a larger sum of individual income.

FIGURE 11: EV LAWS AND INCENTIVES (2020)

22

Note: Darker color indicates a greater number of laws and incentives; California leads at 104.

FIGURE 12: SPLIT OF VEHICLE REGISTRATIONS BY STATE (TOP 10) (2018)

23

22

“Electric Vehicle Laws and Incentives by State” (chart), “Maps and Data — Electric Vehicle Laws and Incentives

by State” (webpage), Alternative Fuels Data Center, Alternate Fuels Data Center, Office of Energy Efficiency &

Renewable Energy, U.S. Department of Energy, accessed October 22, 2020, available at

https://afdc.energy.gov/data/10373.

23

“U.S. Automobile Registrations in 2018, by State,” Statista, March 2021,

https://www.statista.com/statistics/196010/total-number-of-registered-automobiles-in-the-us-by-state/; “Electric

Vehicle Registrations by State”

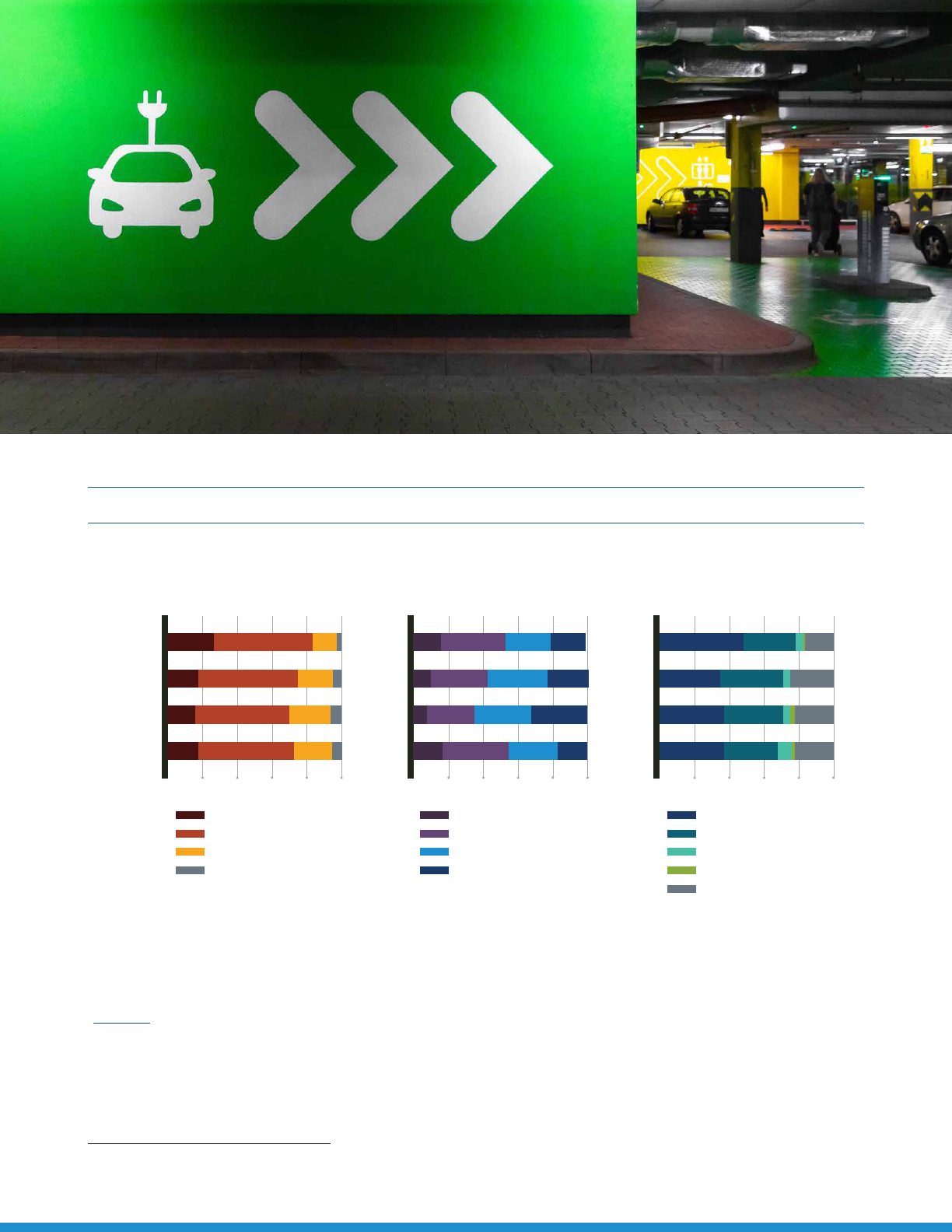

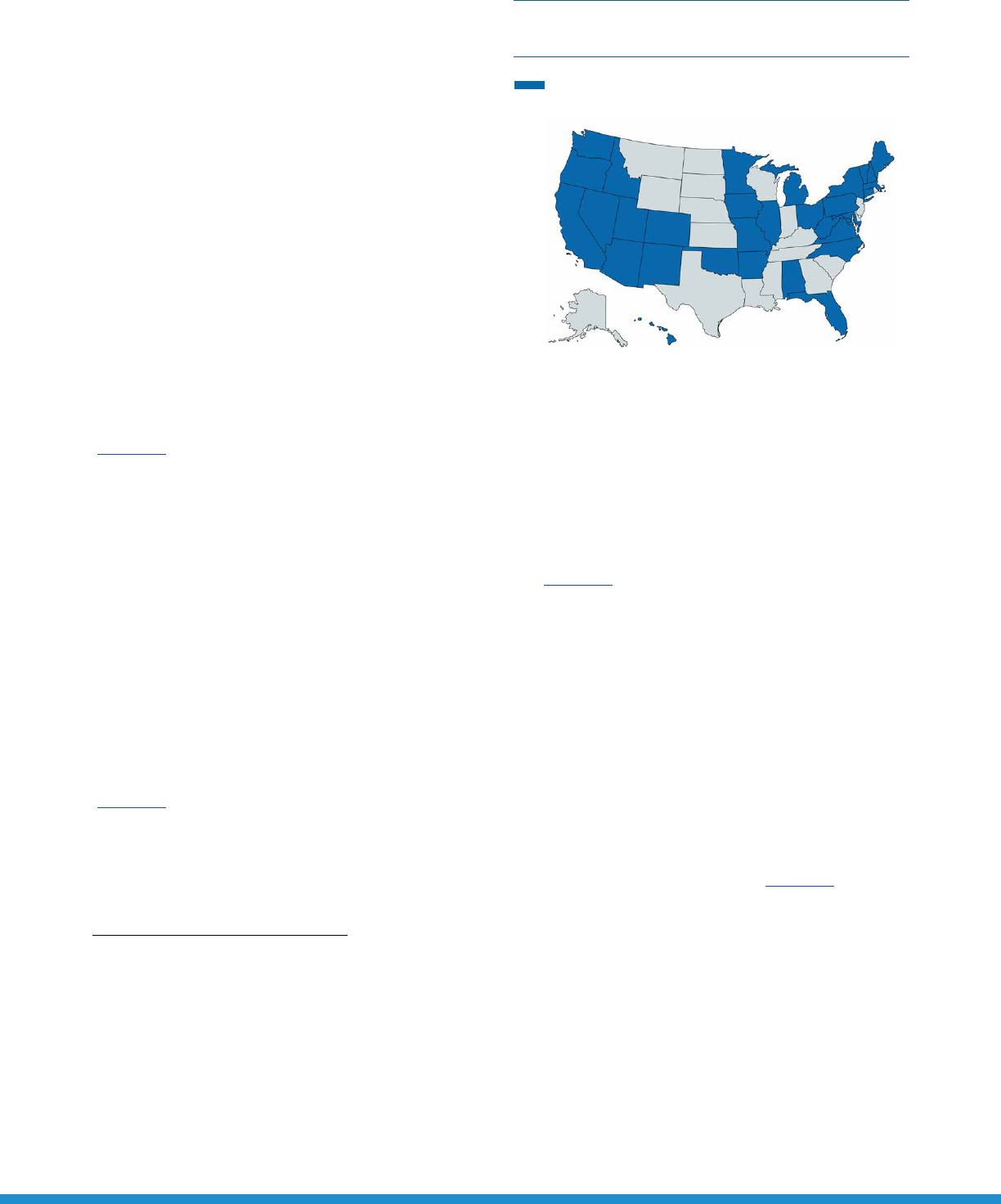

Distribution of BEVs is concentrated along the

ZEV (zero-emission vehicle) belt (Figure 9).

17

BEV registrations in California in 2018 were

approximately 256,000, which was roughly equal to

the BEV registrations in all other states combined

(approximately 286,000).

18

17 “Electric Vehicle Registrations by State,” National Renewable Energy Laboratory, printed March 7, 2020, updated August 2020, accessed October 20, 2020, available at

https://afdc.energy.gov/data/10962.

18 “Electric Vehicle Registrations by State;” “U.S. Automobile Registrations in 2018, by State,” Statista, March 2021, https://www.statista.com/statistics/196010/total-

number-ofregistered-automobiles-in-the-us-by-state/.

19 “SOI Tax Stats — Individual Income Tax Statistics — 2018 ZIP Code Data (SOI),” Internal Revenue Service, 2018, accessed October 20, 2020, available at https://www.irs.

gov/statistics/soi-tax-stats-individual-income-tax-statistics-2018-zip-code-data-soi.

20 “Electric Vehicle Laws and Incentives by State” (chart), “Maps and Data — Electric Vehicle Laws and Incentives by State” (webpage), Alternative Fuels Data Center, Oice

of Energy Eiciency and Renewable Energy, U.S. Department of Energy, accessed October 22, 2020, available at https://afdc.energy.gov/data/10373.“““

21 “Electric Vehicle Registrations by State;” “U.S. Automobile Registrations in 2018, by State”

This distribution appears to correspond with

individual income in each state (Figure 10)

19

and the

EV policies and incentives in each state (Figure 11).

20

When compared to the overall number of vehicles

registered by state, EVs constitute a very small

percentage (Figure 12).

21

High Income

104

Low Income

0

DRAFT

20

Note: Total registrations in California is 256,000 but the legend ends at 30,000 to highlight the variation in other states.

Distribution of BEVs is concentrated along the ZEV (zero-emission vehicle) belt.

18

BEV

registrations in California in 2018 were approximately 256,000, which was roughly equal to the

BEV registrations in all other states combined (approximately 286,000).

19

This distribution appears

to correspond with individual income in each state (Figure 10) and the EV policies and incentives

in each state (Figure 11). When compared to the overall number of vehicles registered by state,

EVs constitute a very small percentage (Figure 12).

20

FIGURE 10: INDIVIDUAL INCOME BY STATE (2018)

21

18

“Electric Vehicle Registrations by State”

19

“Electric Vehicle Registrations by State”

20

“Electric Vehicle Registrations by State”; U.S. Automobile Registrations in 2018, by State”

21

“SOI Tax Stats — Individual Income Tax Statistics — 2018 ZIP Code Data (SOI),” Internal Revenue Service,

2018, accessed October 20, 2020, available at https://www.irs.gov/statistics/soi-tax-stats-individual-income-tax-

statistics-2018-zip-code-data-soi.

FIGURE 9: HEATMAP OF BEV POPULATION BASED

ON NUMBER OF REGISTRATIONS BY STATE (2018)

DRAFT

20

Note: Total registrations in California is 256,000 but the legend ends at 30,000 to highlight the variation in other states.

Distribution of BEVs is concentrated along the ZEV (zero-emission vehicle) belt.

18

BEV

registrations in California in 2018 were approximately 256,000, which was roughly equal to the

BEV registrations in all other states combined (approximately 286,000).

19

This distribution appears

to correspond with individual income in each state (Figure 10) and the EV policies and incentives

in each state (Figure 11). When compared to the overall number of vehicles registered by state,

EVs constitute a very small percentage (Figure 12).

20

FIGURE 10: INDIVIDUAL INCOME BY STATE (2018)

21

18

“Electric Vehicle Registrations by State”

19

“Electric Vehicle Registrations by State”

20

“Electric Vehicle Registrations by State”; U.S. Automobile Registrations in 2018, by State”

21

“SOI Tax Stats — Individual Income Tax Statistics — 2018 ZIP Code Data (SOI),” Internal Revenue Service,

2018, accessed October 20, 2020, available at https://www.irs.gov/statistics/soi-tax-stats-individual-income-tax-

statistics-2018-zip-code-data-soi.

30,000100

Note: Total registrations in California is 256,000 but the legend ends at

30,000 to highlight the variation in other states.

Source: “Electric Vehicle Registrations by State,” National Renewable

Energy Laboratory

Note: Darker color indicates a larger sum of individual income.

Source: “SOI Tax Stats — Individual Income Tax Statistics — 2018 ZIP Code

Data (SOI),” Internal Revenue Service

Note: Darker color indicates a greater number of laws and incentives;

California leads at 104.

Source: “Electric Vehicle Laws and Incentives by State” (chart), “Maps

and Data — Electric Vehicle Laws and Incentives by State” (webpage),

Alternative Fuels Data Center

FUELS INSTITUTE | EVC | EV CONSUMER BEHAVIOR

15

FUELS INSTITUTE | EVC | EV CONSUMER BEHAVIOR

15

Distribution of BEVs is

concentrated along the ZEV

(zero-emission vehicle) belt.

BEV registrations in California

in 2018 were approximately

256,000, which was roughly

equal to the BEV registrations

in all other states combined

(approximately 286,000).

FUELS INSTITUTE | EVC | EV CONSUMER BEHAVIOR

16

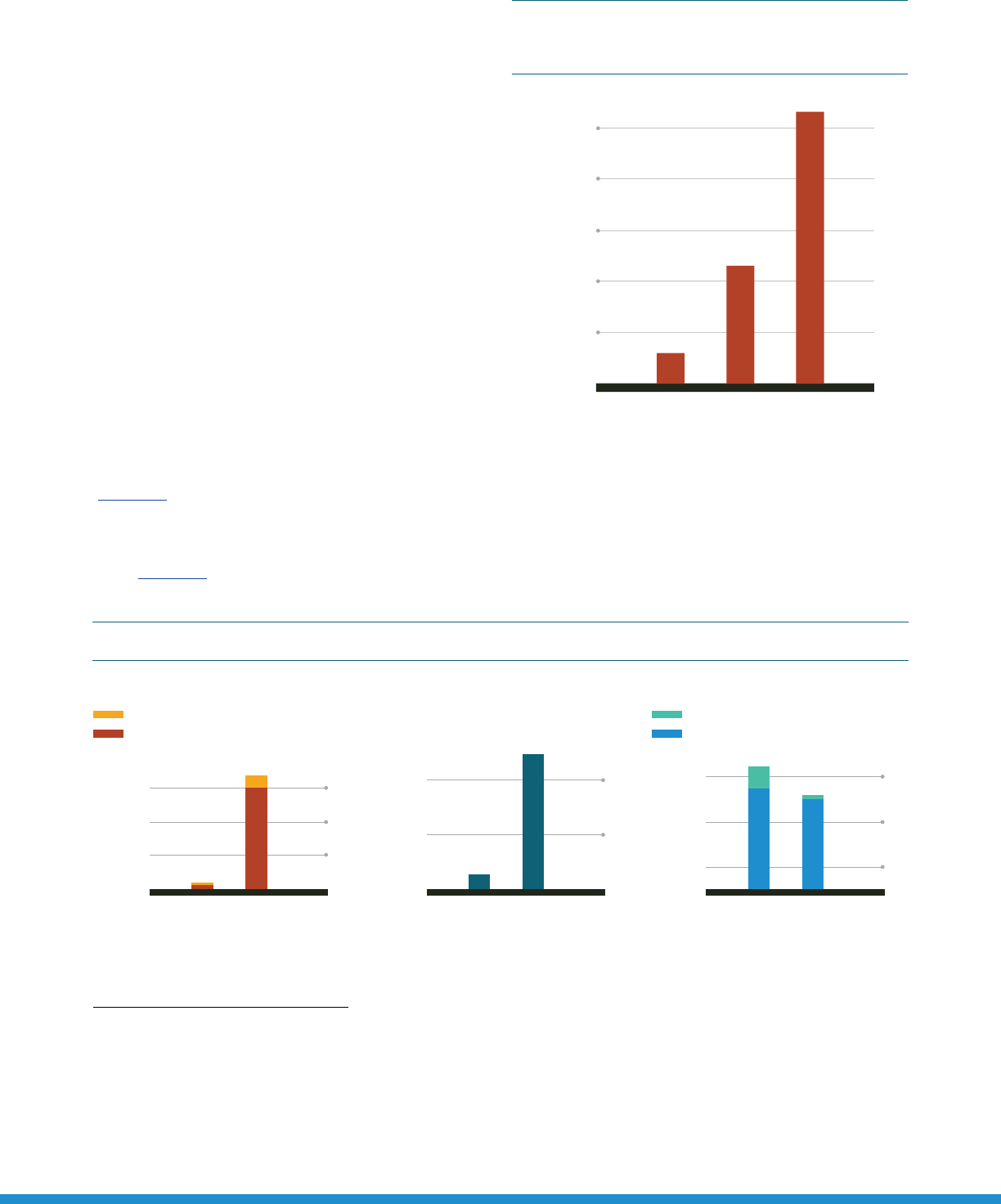

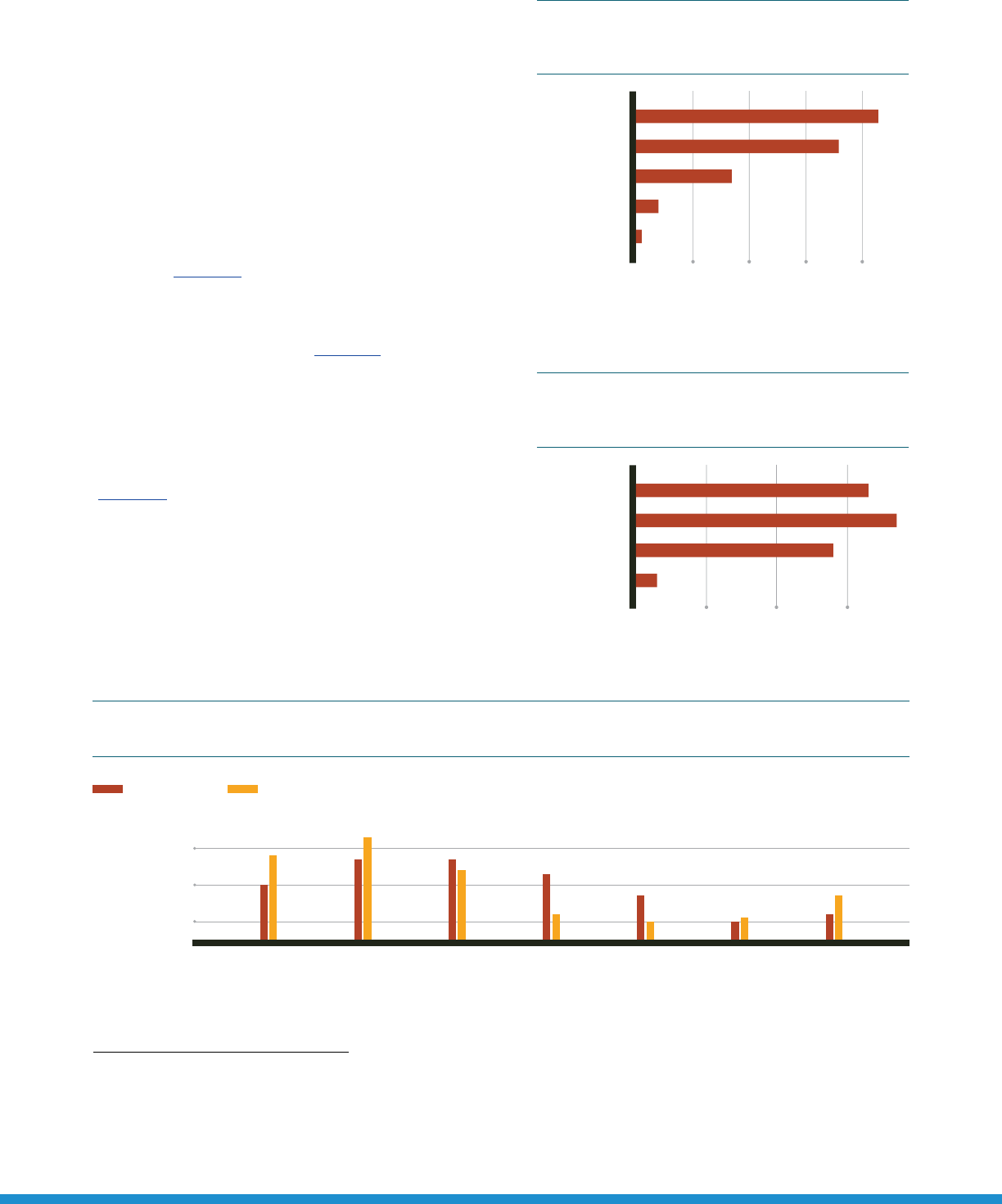

Despite having the highest number of EV

registrations in the U.S., California’s BEV

population still comprises only approximately

1.7% of the state’s overall vehicle registrations

(Figure 12). In each of the 10 states with the most

EV registrations, those registrations constituted

less than 1% of all state vehicle registrations

in 2018.

Daily commute lengths of PEV drivers

According to the Federal Highway Administration,

in 2017, self-estimated annual mileage indicates

an average daily commute between 20 and 35

miles.

22

For EV drivers, however, the average

daily commute length is estimated to be

between 31 and 39 miles.

23

One reason for this

observed trend could be BEVs have a lower

cost of fuel and maintenance compared to an

ICE-powered vehicle — estimated by AAA as

57% lesser and 65% lesser, respectively. Most

EV owners also own a second vehicle in the

household, which could be a conventional

vehicle. Given the cheaper operating cost of a

BEV compared to a conventional vehicle, owners

might prefer to use the BEV for a higher number

of trips.

24

Another reason could be that the

constant increase of both average EV battery

range and charging infrastructure has reduced

range anxiety for drivers.

EVOLUTION OF EV BUYER DEMOGRAPHICS

AND BEHAVIOR OVER THE PAST 10 YEARS

BEV production in the U.S. has been

experiencing exponential growth aided by falling

battery prices.

25

The spike in 2018 coincides with

the Tesla Model 3 introduction (Figure 13).

26

22 N. McGuckin and A. Fucci, Summary of Travel Trends: 2017 National Household Travel Survey (Washington, DC: Federal Highway Administration, July 2018), available at

https://nhts.ornl.gov/assets/2017_nhts_summary_travel_trends.pdf.

23 Ellen Edmonds, “AAA: Owning an Electric Vehicle is the Cure for Most Consumer Concerns”; Daniel Boston and Alyssa Werthman, “Plug-in Vehicle Behaviors: An Analysis

of Charging and Driving Behavior of Ford Plug-In Electric Vehicles in the Real World,” World Electric Vehicle Journal 8 (2016): 926-935, https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj8040926.

24 Ellen Edmonds, “AAA: Owning an Electric Vehicle is the Cure for Most Consumer Concerns”

25 Colin McKerracher, Ali Izadi-Najafabadi, Aleksandra O’Donovan, Nick Albanese, Nikolas Soulopolous, David Doherty, Milo Boers, et al, Electric Vehicle Outlook 2020

(Bloomberg New Energy Finance, 2020), https://about.bnef.com/electric-vehicle-outlook/.

26 IHS Markit, subscription-only database and forecast utility, accessed October 1, 2020, https://ihsmarkit.com/

United Sates

of America

Conventional

SUV

PHEV

BEV

Sedan

Trucks

Conventional Electric

New Car Buyers

Positive/negative

opinion about

electric vehicles

100,000

200,000

300,000

400,000

500,000

4000

0.00M

0.00M

0.00M

21% 12% 10% 57%

20% 16% 4% 60%

31% 19% 10% 40%

39% 18% 9% 34%

37% 20% 10% 33%

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

0.05M

0.07M

0.07M

0.10M

0.14M

0.31M

0.41M

100,000

200,000

300,000

400,000

500,000

0.00M

0.00M

0.00M

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

0.05M

0.07M

0.07M

0.10M

0.14M

0.31M

0.41M

2,677

5,461

10,560

11,242

29.2 32.8 35.8 39.4 41.4 39.9 41.2 41.3

2,677

FIGURE 13: BEV PRODUCTION IN THE U.S.

(2010-2019)

United Sates

of America

Conventional

SUV

PHEV

BEV

Sedan

Trucks

Conventional Electric

New Car Buyers

Positive/negative

opinion about

electric vehicles

4000

98.3%

1.7%

99.0%

1.0%

99.7%

0.3%

99.7%

0.3%

99.6%

0.4%

99.6%

0.4%

99.4%

0.6%

99.7%

0.3%

99.2%

0.8%

99.6%

0.4%

21% 12% 10% 57%

20% 16% 4% 60%

31% 19% 10% 40%

39% 18% 9% 34%

37% 20% 10% 33%

CA

WA

FL

TX

NY

GA

AZ

IL

OR

NJ

2,677

5,461

10,560

11,242

29.2 32.8 35.8 39.4 41.4 39.9 41.2 41.3

2,677

FIGURE 12: SPLIT OF VEHICLE REGISTRATIONS

BY STATE (TOP 10) (2018)

BEV

Others

Source: “Electric Vehicle Registrations by State;” “U.S. Automobile

Registrations in 2018, by State”

Source: IHS Markit

FUELS INSTITUTE | EVC | EV CONSUMER BEHAVIOR

17

BUSINESS AS USUAL

Utility/Contribution in Aid of Construction Host Site Investment

AGE 40–44

UTILITY INCENTIVE

2012

45–54

2015

40–55

AVERAGE INCOME $114k $114–150k $125–150k

RESIDENCE 90% vehicle garage 90% vehicle garage no public data

MILEAGE ~100 per week ~180 per week ~250 per week

GENDER 67% male 74% male 75% male

2019

Utility/Contribution in Aid of Construction Host Site Investment

MAKE-READY

Utility Investment Host Site Investment

OWNER-OPERATOR

Utility Investment

Utility Incentive Payments

Positive/negative

opinion about

electric vehicles

UTILITY

DISTRIBUTION

NETWORK

Service Connection Supply Infrastructure Charger Equipment

METER CONDUCTOR

(BORING/

TRENCHING)

EV CHARGER ELECTRIC

VEHICLE

PANELUTILITY

PAD-MOUNTED

TRANSFORMER

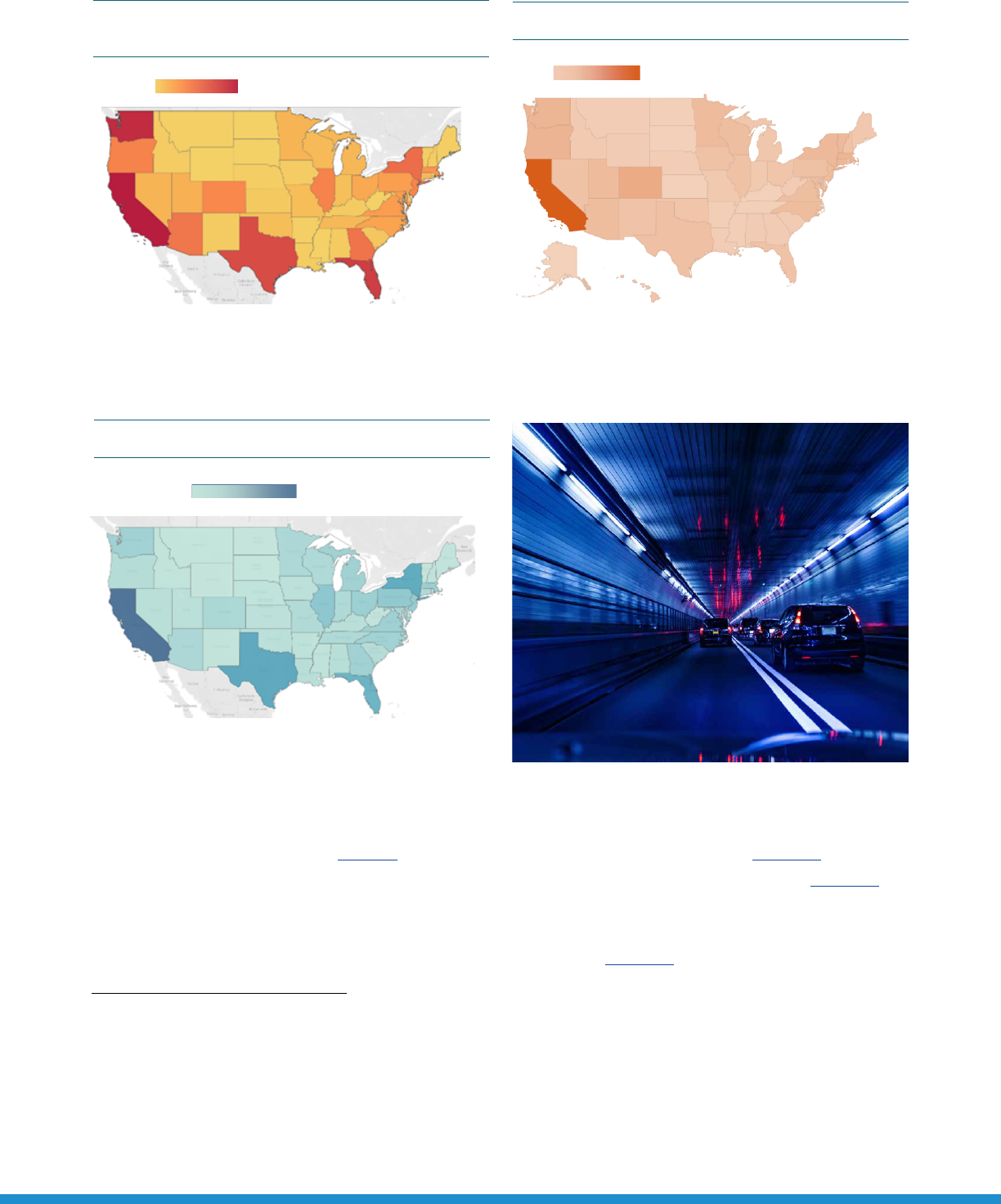

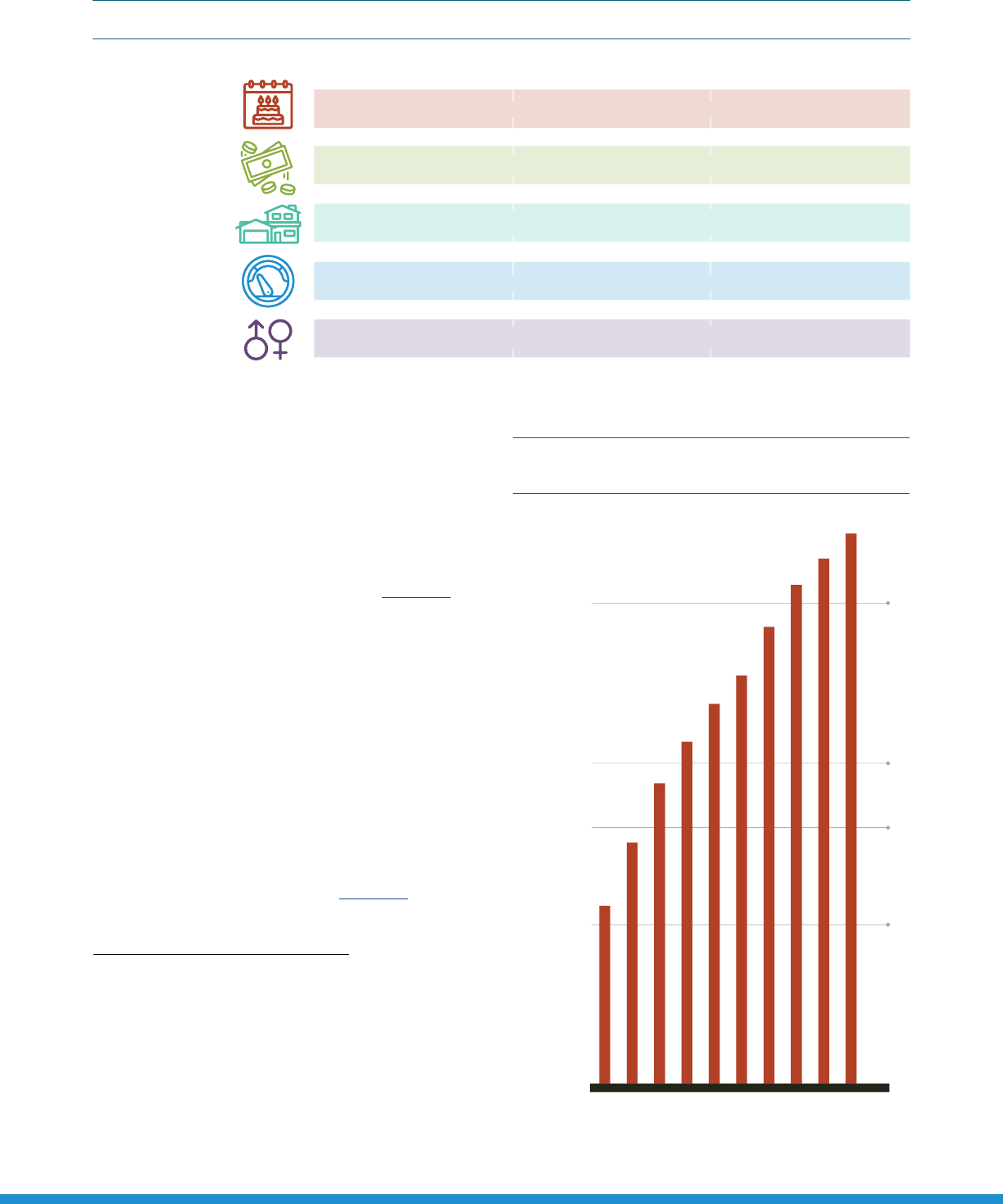

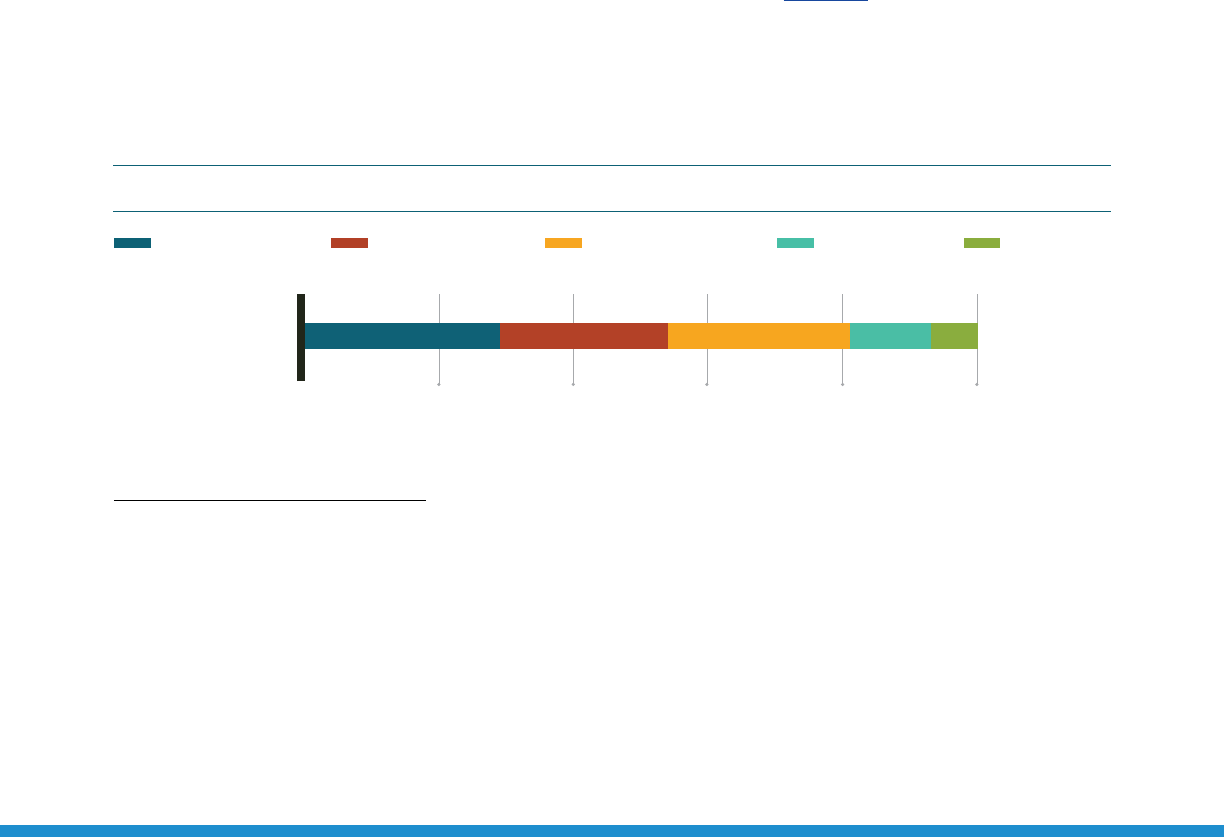

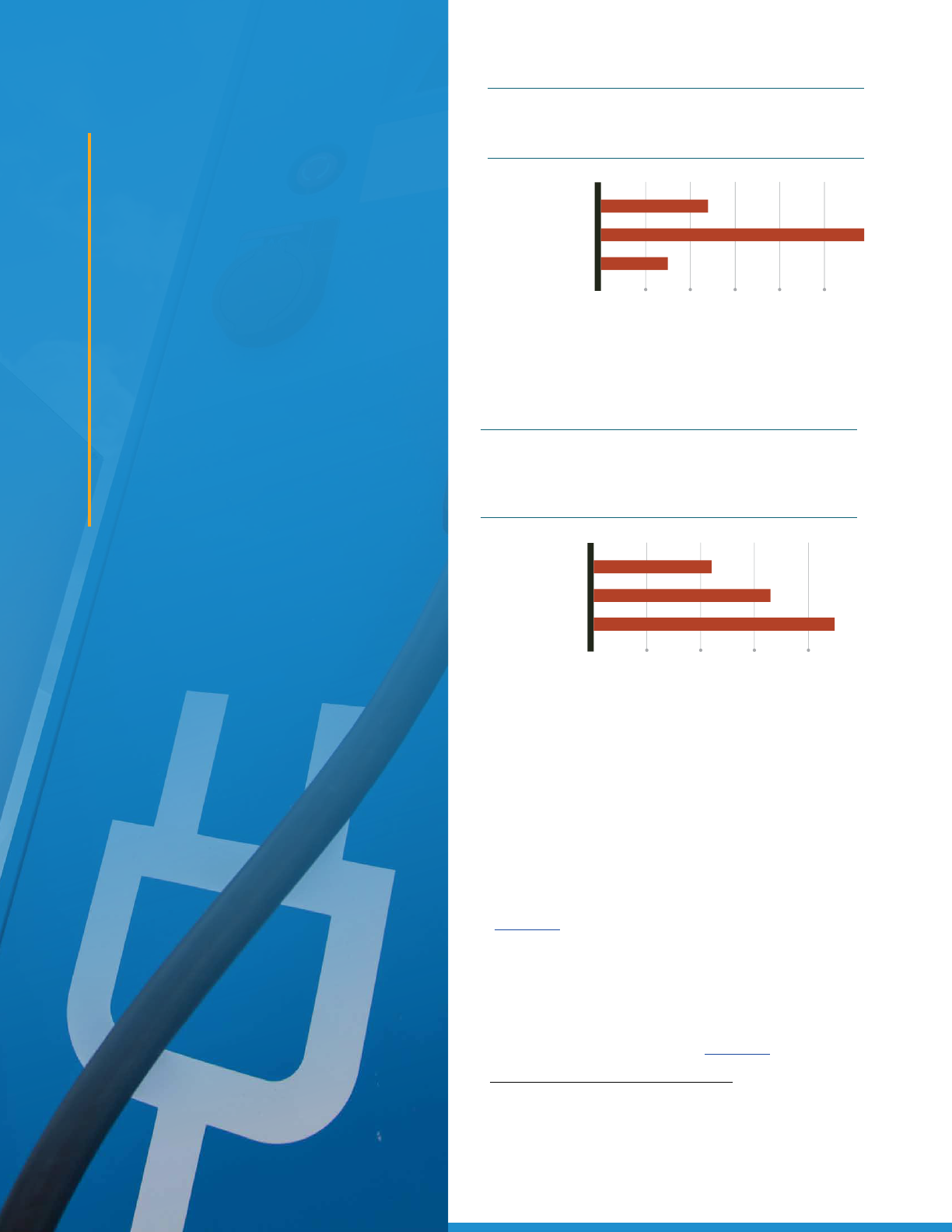

The PEV buyer’s age group has stayed the same

over the years (Figure 14).

27

The average household

annual income has been consistently over $100,000.

28

Most PEV owners have had a garage with an outlet to

charge their vehicle.

29

PEV buyers have mostly been

male.

30

Mileage traveled, however, has increased

from 100 miles a week to 250 miles a week over the

past 10 years.

31

This could be attributed to the fact

that both the average battery range on a typical EV

and the charging infrastructure have been growing

constantly, which helps ease range anxiety for

buyers. In addition to this, the cost of operating

an EV is less than that of a conventional vehicle,

27 Deloitte Consulting LLP, Gaining Traction: A Customer View of Electric Vehicle Mass Adoption in the U.S. Automotive Market, 2010, https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/

read/4198231/gaining-traction-a-customer-view-of-electric-vehicle-mass-adoption-in; Chris Woodyard, “Study: Electric Car Buyers Are Younger but Richer,” USA Today, May

4, 2015, updated May 7, 2015, https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/cars/2015/05/04/truecar-study-electric-cars-richer/26884511/; “EV Consumer Survey Dashboard,”

California Clean Vehicle Rebate Project, accessed October 5, 2020, available at https://cleanvehiclerebate.org/eng/survey-dashboard/ev; Daniel Boston and Alyssa

Werthman, “Plug-in Vehicle Behaviors”; “New Car Buyer Demographics 2020 (Updated)”

28 Electric Power Research Institute, Inc., Plug-In Electric Vehicle Multi-State Market and Charging Survey, February 26, 2016, available at https://www.epri.com/research/

products/000000003002007495; Deloitte Consulting LLP, Gaining Traction; Christopher Butler, “Electric Vehicle Prices Finally in Reach of Millennial, Gen Z Car Buyers”

29 Electric Power Research Institute, Inc., Plug-In Electric Vehicle Multi-State Market and Charging Survey, February 26, 2016, available at https://www.epri.com/research/

products/000000003002007495. Deloitte Consulting LLP, Gaining Traction

30 Deloitte Consulting LLP, Gaining Traction; Mark Kane, “Annual Electric Miles Traveled Varies Widely For 8 Plug-In Electric Cars,” InsideEVs, May 16, 2015, https://insideevs.

com/news/325893/annual-electric-miles-traveled-varies-widely-for-8-plug-in-electric-cars/.

31 Deloitte Consulting LLP, Gaining Traction; Mark Kane, “Annual Electric Miles Traveled Varies Widely For 8 Plug-In Electric Cars”; Ellen Edmonds, “AAA: Owning an Electric

Vehicle is the Cure for Most Consumer Concerns”

32 Ellen Edmonds, “AAA: Owning an Electric Vehicle is the Cure for Most Consumer Concerns”

33 Ricardo research

34 Annie Palmer, “Amazon Debuts Electric Delivery Vans Created with Rivian,” CNBC, October 8, 2020, updated October 8, 2020, https://www.cnbc.com/2020/10/08/

amazon-new-electric-delivery-vans-created-with-rivian-unveiled.html.

encouraging drivers to drive their EVs more than

their other conventional vehicle(s).

32

The EV fleet has grown over the past 10 years where

commercial fleet operators have gained more

experience in deploying EVs in the field. EV usage in

the commercial sector has evolved from limited-use

transit bus applications to medium- and heavy-duty

vehicles, delivery vans, and light-duty trucks.

33

A very

recent example to this is Amazon’s 2020 investment

in Rivian to provide vans for its fleet.

34

FIGURE 14: EVOLUTION OF KEY EV BUYER DEMOGRAPHICS (2012-2021)

FUELS INSTITUTE | EVC | EV CONSUMER BEHAVIOR

18

United Sates

of America

Conventional

SUV

PHEV

BEV

Sedan

Trucks

Conventional Electric

New Car Buyers

Positive/negative

opinion about

electric vehicles

500,000

1,000,000

1,500,000

2,000,000

4000

0.55M

0.75M

0.94M

21% 12% 10% 57%

20% 16% 4% 60%

31% 19% 10% 40%

39% 18% 9% 34%

37% 20% 10% 33%

2021

2022

2023

2024

2025

2026

2027

2028

2029

2030

1.075M

1.18M

1.27M

1.42M

1.56M

1.64M

1.72M

2,677

5,461

10,560

11,242

29.2 32.8 35.8 39.4 41.4 39.9 41.2 41.3

2,677

ANTICIPATED EVOLUTION OF EV BUYER

DEMOGRAPHICS AND BEHAVIOR OVER

THE NEXT 10 YEARS

BEV production is expected to steadily grow within

the next decade. At some point, BEVs are expected

to reach price parity with ICE vehicles (Figure 15).

Companies such as Volkswagen and Volvo expect to

generate at least 40% of their sales from EVs by 2025;

most other auto OEMs are expected to follow this

trend.

35

By 2030, up to 40% of all new car sales

could be EVs.

36

Given that the number of available

EV segments is expected to broaden, the cost

of owning an EV is forecast to be on par with a

conventional vehicle, and charging infrastructure

is estimated to grow to meet the demand,

37

the EV

buyer demographic could normalize with the new

car buyer over the next 10 years (Figure 16).

35 Tim Levin, “All the Things Carmakers Say They’ll Accomplish with Their Future

Electric Vehicles Between Now and 2030,” Business Insider, January 28, 2020,

https://www.businessinsider.com/promises-carmakers-have-made-about-their-

future-electric-vehicles-2020-1.

36 McKerracher et al, Electric Vehicle Outlook 2020; U.S. Drive, Summary Report

on EVs at Scale and the U.S. Electric Power System, November 2019, https://www.

energy.gov/sites/prod/files/2019/12/f69/GITT%20ISATT%20EVs%20at%20Scale%20

Grid%20Summary%20Report%20FINAL%20Nov2019.pdf.

37 Hao Wu, Genevieve Alberts, James Hooper, and Bryn Walton, New Market. New

Entrants. New Challenges. Battery Electric Vehicles (London, UK: Deloitte LLP, 2019),

https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/uk/Documents/manufacturing/

deloitte-uk-battery-electric-vehicles.pdf.

BUSINESS AS USUAL

Utility/Contribution in Aid of Construction Host Site Investment

AGE

UTILITY INCENTIVE

2021 2025

AVERAGE INCOME

RESIDENCE

MILEAGE

GENDER

2030

Utility/Contribution in Aid of Construction Host Site Investment

MAKE-READY

Utility Investment Host Site Investment

OWNER-OPERATOR

Utility Investment

Utility Incentive Payments

Positive/negative

opinion about

electric vehicles

Average income bracket is expected to drop down from the current bracket

as EVs become more affordable.

Number of EV drivers with no provision to charge at home is expected to increase as

availability of public charging points increases along with the range of vehicles.

Driving pattern is expected to be similar to the way ICE vehicles are driven.

Gender distribution is expected to be more balanced with the launch of new vehicles

in various segments with better range estimators.

The average age is expected to normalize with the broader new-vehicle buyer trend.

UTILITY

DISTRIBUTION

NETWORK

Service Connection Supply Infrastructure Charger Equipment

METER CONDUCTOR

(BORING/

TRENCHING)

EV CHARGER ELECTRIC

VEHICLE

PANELUTILITY

PAD-MOUNTED

TRANSFORMER

FIGURE 16: EXPECTED EVOLUTION OF KEY EV BUYER DEMOGRAPHICS (2021-2030)

FIGURE 15: EXPECTED BEV PRODUCTION IN THE

U.S. (2021-2030)

FUELS INSTITUTE | EVC | EV CONSUMER BEHAVIOR

19

According to a survey conducted by Volvo, more than

half of respondents said they are likely to purchase

an EV if the price is the same as an ICE vehicle.

38

The

industry expectation that EV to ICE price parity may

be realized in the coming decade would mean that

EVs could be aordable to a broader consumer base.

This will increase the probability of buyers with an

annual household income of less than $100,000 to

consider an EV for their next vehicle, thus pushing

the average EV owner income bracket down from

where it currently sits.

Bloomberg New Energy Finance predicts the ratio

of EVs to public charging points is expected to reach

40-50 EVs per public charging point by 2040,

39

and as

hardware costs fall and technology is commoditized,

Wood Mackenzie predicts that there could be as many

as 1.2 million public charging points in North America

by 2030.

40

This increase in availability of public

chargers could help potential consumers without

access to a charger at home consider buying an EV.

38 Volvo Car USA, The State of Electric Vehicles in America, February 26, 2019, https://www.media.volvocars.com/us/en-us/media/documentfile/249123/volvo-reports-the-

state-of-electric-vehicles-in-america.

39 McKerracher et al., Electric Vehicle Outlook 2020

40 Jason Deign, “Up to 40 Million EV Charging Points Forecast Worldwide by 2030,” Green Tech Media, August 9, 2018, https://www.greentechmedia.com/articles/read/

electric-vehicle-charging-points-40-million-gtm.

41 Castrol, Accelerating the EVolution: The Tipping Points to Mainstream Electric Vehicle Adoption, 2020, https://www.castrol.com/content/dam/castrol/master-site/en/

global/home/technology-and-innovation/electric-vehicle-adoption/accelerating_the_evolution_study.pdf.

42 “Average Annual Miles per Driver by Age Group,” Federal Highway Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation, March 29, 2018, accessed October 15, 2020,

available at https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ohim/onh00/bar8.htm.

43 Dave Vanderwerp, “EV Range: Everything You Need to Know,” Car and Driver, May 22, 2020, https://www.caranddriver.com/shopping-advice/a32603216/ev-range-

explained/.

44 “New Car Buyer Demographics 2020 (Updated)”

45 Nicolette Caperello, Jennifer TyreeHageman, and Ken Kurani, “Engendering the Future of Electric Vehicles: Conversations with Men and Women” (presentation,

Women’s Issues in Transportation 5th International Conference, Paris, France, April 14-16, 2014) available at https://phev.ucdavis.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/2014-

UCD-ITS-RP-14-101.pdf.

46 Kristy Hartman and Emily Dowd, “State Eorts to Promote Hybrid and Electric Vehicles,” National Conference of State Legislatures, September 26, 2017, https://www.

ncsl.org/research/energy/state-electric-vehicle-incentives-state-chart.aspx.

47

David Shepardson and Nichola Groom, “California Passes Landmark Mandate for Zero Emission Trucks,” Reuters, June 25, 2020, https://ca.reuters.com/article/idUSKBN23W31N.

Potential owners are inclined to purchase a BEV

if it delivers a range of approximately 320 miles.

41

Given that Americans drive an average of 260 miles

a week,

42

potential BEV buyers expect to get at least

a week of driving range on a single charge. Many

vehicles today oer more than 200 miles of range,

43

and the trend has been constant growth in

BEV range. BEVs are expected to be driven

like liquid-fuel-powered vehicles today, so

the driving distance on a BEV is expected to

be on par with the overall trend.

There appears to be a balanced distribution

between the two genders in purchases of

SUVs and sedans, however, the average

EV customer is predominantly male.

44

According to a study by the University of

California, Davis, amongst other reasons,

female EV early adopters largely distrusted the range

estimator.

45

There could be more female EV drivers

when newer technology enables more accurate

range predictors and perhaps better range as well.

The EV fleet is expected to grow in the upcoming

years, primarily driven by state mandates.

California and 27 other states have hybrid or EV

fleet requirements, acquisition goals, or a stated

preference for purchasing hybrid or EVs to be used

in the state’s fleet.

46

For example, California’s 2020

mandate requiring 5-9% of 2024 model year trucks,

based on class, to be ZEVs is expected to expand to

have 30-50% of trucks to be ZEVs by 2030 and 100%

where feasible by 2045.

47

The EV fleet is expected to grow in the

upcoming years, primarily driven by state

mandates. California and 27 other states have

hybrid or EV fleet requirements, acquisition

goals, or a stated preference for purchasing

hybrid or EVs to be used in the state’s fleet.

FUELS INSTITUTE | EVC | EV CONSUMER BEHAVIOR

20

DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS AND

THEIR RELATIONSHIP WITH EV OWNERSHIP

AND BEHAVIOR

Currently, EVs are predominantly sedans or

hatchbacks, which may not cater to the requirement

of SUV, truck, and minivan drivers. In a 2019 study,

the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) and

Consumer Reports reported a strong consensus

(72%) that PEVs should be produced in other forms,

48

so they may address the requirements of drivers of

these vehicles.

In the same study, approximately half of all

prospective EV buyers reported a belief that the

federal government should invest money to help

consumers buy PEVs. In addition, this belief is more

prevalent in people of color (62% people of color

versus 53% of all new car buyers).

49

48 Union of Concerned Scientists and Consumer Reports, Electric Vehicle Survey Findings and Methodology, July 2019, https://advocacy.consumerreports.org/wp-content/

uploads/2019/07/ConsumerReports-UnionofConcernedScientists-2019-EV_Survey-7.17.19.pdf.

49 Union of Concerned Scientists and Consumer Reports, Electric Vehicle Survey Findings and Methodology

50 Christopher Butler, “Electric Vehicle Prices Finally in Reach of Millennial, Gen Z Car Buyers”

51 Union of Concerned Scientists and Consumer Reports, Electric Vehicle Survey Findings and Methodology; John Kiser and Mark Essery, Is There a Target Market for Electric

Vehicles?, Ipsos, March 27, 2017, https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/2017-04/ipsos-marketing-target-market-electric-vehicles.PD__0.pdf.

52 Union of Concerned Scientists and Consumer Reports, Electric Vehicle Survey Findings and Methodology

Another key theme is that younger people between

the age of 25 and 34 may not be able to aord EVs

due to factors such as student debt, wage stagnation,

and lack of access to home charging or at-home

parking. Some report using public transportation to

be more practical than owning a car.

50

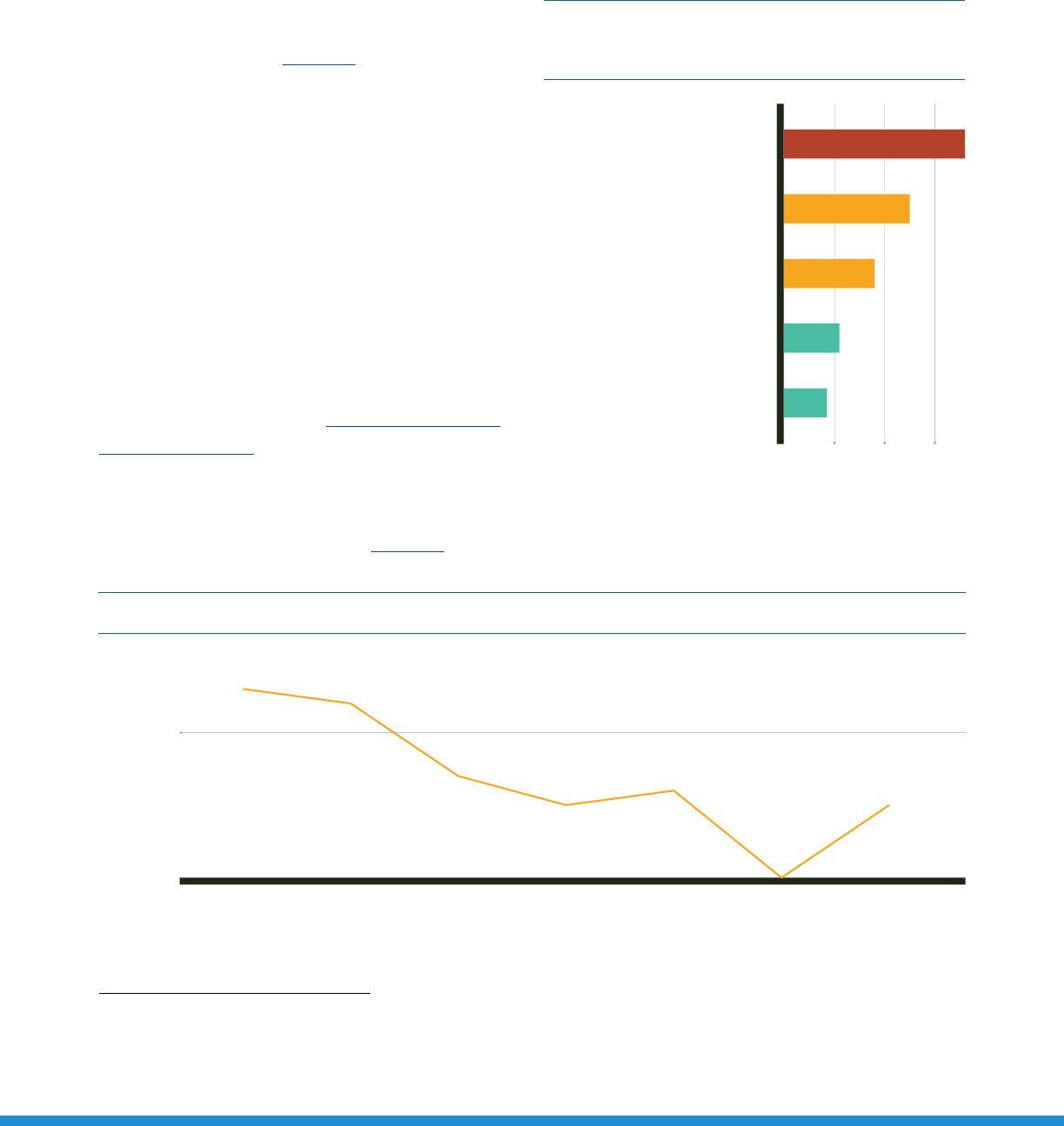

PEV buyers appear to value aordability by means

of a lower purchase price, lower operating costs,

and federal and/or state support, amongst others

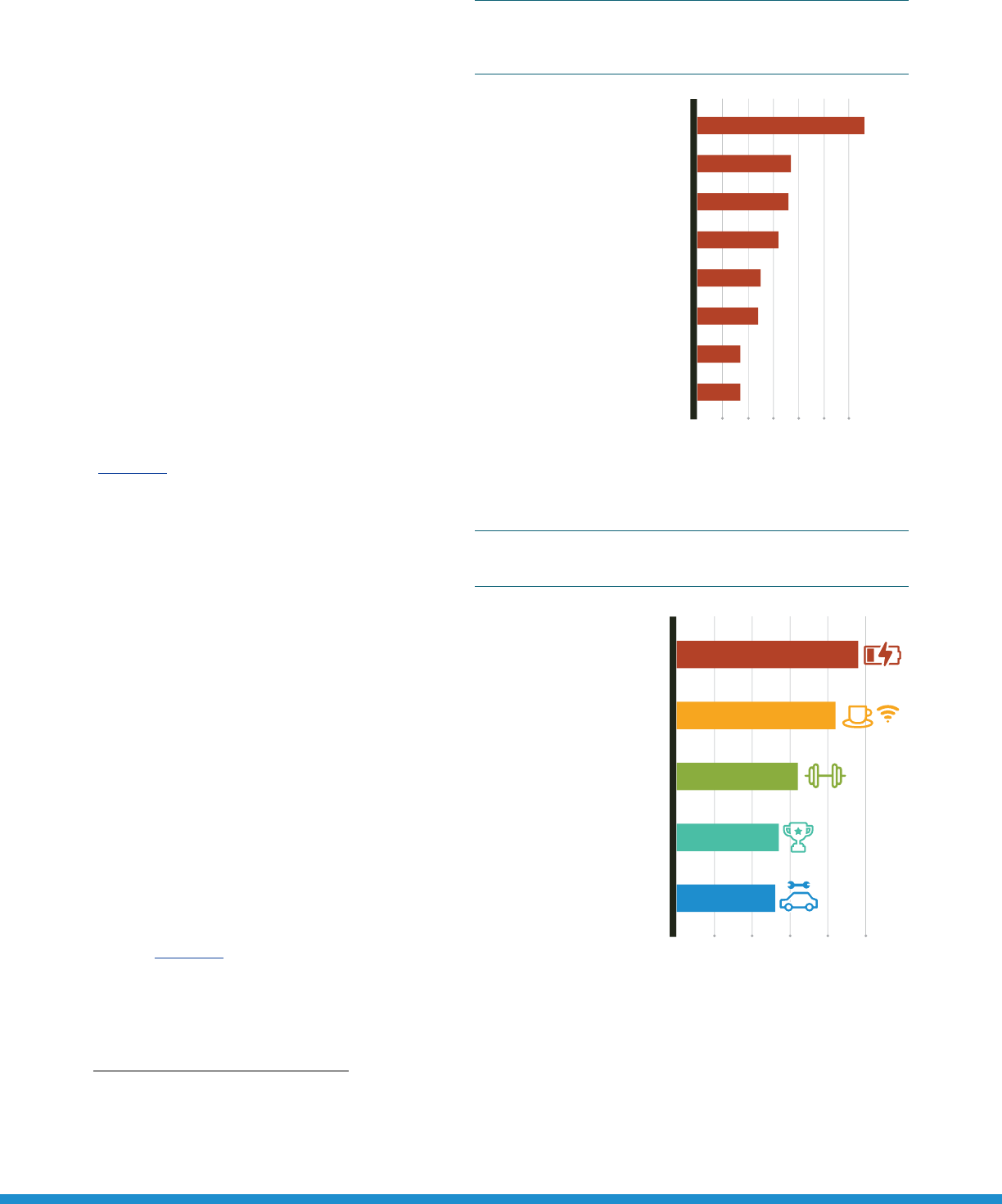

(Figure 17).

51

They expect a PEV to be time-saving by

charging quickly and having a long range. Charger

availability at home and in public places appears

important to prospective PEV buyers. Some of those

surveyed

feel that familiarity with the technology

could encourage a purchase,

52

such as while renting

a PEV and riding in a PEV ride-share or taxi. Potential

buyers value choices in form and attractive vehicle

design, amongst other factors, that could help them

decide to purchase an EV.

AFFORDABILITY TIME SAVING

CHARGER

AVAILABILITY

FAMILIARITY OPTIONS

MAKE-READY

Utility Investment Host Site Investment

Utility Incentive Payments

Positive/negative

opinion about

electric vehicles

Lower purchase

price

Lower operating

costs

Federal/state

incentive

Free EVSE

installation at home

Special rates

from utility

Long range

between charges

Short charging

time

Ability to charge

at home

More public

charging stations

Ability to charge

at work

Renting a plug-in

vehicle

Friend/family

recommend

Riding in PEV as

taxi/rideshare

Plug-in crossovers/

SUV/pickup

Ability to charge

wirelessly

Used PEV

options

Attractive vehicle

design

UTILITY

DISTRIBUTION

NETWORK

Service Connection

FIGURE 17: FACTORS INFLUENCING LIKELINESS OF PEV PURCHASE (2017-2019)

Source: Union of Concerned Scientists and Consumer Reports, Electric

Vehicle Survey Findings and Methodology; John Kiser and Mark Essery,

Is There a Target Market for Electric Vehicles?

FUELS INSTITUTE | EVC | EV CONSUMER BEHAVIOR

21

Decision making for adoption of EVs in

commercial fleet applications is deeply rooted

in viable business case and the ability to meet

operational requirements. Hence, TCO and the

payback period are key metrics considered by

fleets, which are impacted by EV price, cost of

infrastructure, operational cost savings, and residual

value at the end of the vehicle’s primary usage.

Vehicle uptime, duty cycle, range, and payload

requirements are other major factors that fleets

take into consideration. EVs have penetrated several

commercial vehicle on-highway and o-highway

applications, such as transit buses, school buses,

medium-duty delivery vans, yard trucks, forklis,

and heavy-duty on-highway trucks. However,

currently commercial EVs are predominantly used

for local operations, oen involving stop-and-go

duty cycles, where the vehicles return to base and

rely on private charging infrastructure owned and

operated by the fleet.

53

DIFFERENCE IN TRIPS TAKEN IN

EVS VERSUS LIQUID-FUEL VEHICLES

Early adopters found that limited battery range and

lack of widespread availability of public chargers

made longer trips more diicult in EVs. According to

an AAA study, the average EV owner drives 39 miles a

day.

54

This is slightly more than the national average

of all vehicles, which is between 20-35 miles a day.

55

In general, more miles are driven today in an EV than

in a conventional liquid-fueled vehicle, and drivers