Foreword

One of the major priorities of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) is the creation of

affordable housing. The Department administers several Federal programs that assist state and local governments, as

well as nonprofits and other partners, to develop affordable homeownership and rental units for low-income

households. Two of the most important programs are the HOME Investment Partnerships Program (HOME) and the

Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) Program.

Both HOME and CDBG are important resources in the local development of homes and communities. While sharing

similar goals related to improving the living conditions of low-income families, each program differs in its eligible

activities and requirements. In addition, there is a tremendous need for affordable housing in many communities and

these needs often exceed available resources. So, it is important that state and local governments make strategic

decisions about how to spend their HOME and CDBG funds.

HUD’s Office of Affordable Housing Programs, in partnership with HUD’s Office of Block Grant Assistance,

developed this guidebook as a tool for community development practitioners to assist in making these strategic choices

about HOME and CDBG resources for affordable housing. Its purpose is to provide practical guidance on how both

HOME and CDBG requirements are interpreted and to provide examples of how the two funding sources might be

used in tandem. The Department encourages communities to seek strategic, effective, and innovative ways of using

two of its most important affordable housing resources – the HOME and CDBG Programs.

HOME and CDBG

Table of Contents

Introduction........................................................................................................................................................................................... 1

Making Effective Use of Program Resources ......................................................................................................................... 1

Selecting Suitable Activities............................................................................................................................................ 1

Complying with the Rules .............................................................................................................................................. 2

Leveraging CDBG and HOME .................................................................................................................................... 3

Planning for CDBG and HOME.............................................................................................................................................. 3

Assessment of Community Needs................................................................................................................................ 3

Community-Wide Plan.................................................................................................................................................... 3

Individual Project Plan.................................................................................................................................................... 4

How to Use this Model............................................................................................................................................................... 4

About the Model Program Guides ........................................................................................................................................... 5

Chapter 1: HOME and CDBG Basics .............................................................................................................................................6

What is HOME? .......................................................................................................................................................................... 6

HOME Program Partners .......................................................................................................................................................... 6

HOME Program Activities ........................................................................................................................................................ 7

Eligible Costs.................................................................................................................................................................... 7

Prohibited Activities and Costs ..................................................................................................................................... 8

HOME Program Requirements ................................................................................................................................................ 9

Income Eligibility and Verification ...............................................................................................................................9

Subsidy Limits ................................................................................................................................................................10

Affordability Periods .....................................................................................................................................................10

Maximum Value .............................................................................................................................................................10

Property Standards.........................................................................................................................................................11

HOME Administrative Requirements....................................................................................................................................11

Administrative and Planning Costs.............................................................................................................................11

Match ...............................................................................................................................................................................11

Commitment and Expenditure Deadlines .................................................................................................................12

Program Income ............................................................................................................................................................12

Pre-Award Costs ............................................................................................................................................................12

What is CDBG? .........................................................................................................................................................................13

CDBG Program Partners .........................................................................................................................................................13

CDBG Program Activities .......................................................................................................................................................14

Eligible CDBG Activities .............................................................................................................................................14

Ineligible CDBG Activities...........................................................................................................................................15

CDBG National Objectives .....................................................................................................................................................15

Benefit Low- and Moderate-Income Persons ...........................................................................................................16

Elimination of Slum and Blight ...................................................................................................................................17

Urgent Need ...................................................................................................................................................................17

CDBG Administrative Requirements and Caps ...................................................................................................................18

Administrative Cap ........................................................................................................................................................18

Low- and Moderate-Income Benefit Expenditures .................................................................................................18

Public Services Cap........................................................................................................................................................19

Program Income ............................................................................................................................................................19

Timely Use of Funds .....................................................................................................................................................20

Pre-Award Costs ............................................................................................................................................................20

HOME and CDBG

i

Chapter 2: Using HOME and CDBG for Rental Housing ........................................................................................................26

Approaches to Creating Rental Housing ...............................................................................................................................26

Acquisition ......................................................................................................................................................................26

Tenant-Based Rental Assistance..................................................................................................................................27

Rehabilitation..................................................................................................................................................................28

New Construction..........................................................................................................................................................28

Financing and Developing Rental Housing...........................................................................................................................29

Partners............................................................................................................................................................................30

Forms of Assistance ......................................................................................................................................................33

Eligible Projects..............................................................................................................................................................35

Assisted Units.................................................................................................................................................................36

Eligible Costs..................................................................................................................................................................37

Property and Neighborhood Standards .....................................................................................................................38

Other Federal Requirements........................................................................................................................................38

Ongoing Compliance ................................................................................................................................................................38

Affordability Period.......................................................................................................................................................38

Rent Requirements ........................................................................................................................................................39

Income Eligibility...........................................................................................................................................................40

Ongoing Property Quality ............................................................................................................................................41

Chapter 3: Using HOME and CDBG for Homeownership ......................................................................................................42

Approaches to Creating Homebuyer Units ...........................................................................................................................42

Development Approaches............................................................................................................................................42

Direct Homebuyer Subsidy Approach .......................................................................................................................43

Financing and Developing Homebuyer Housing.................................................................................................................46

Eligible Property Types.................................................................................................................................................49

Property Standards.........................................................................................................................................................50

Other Federal Requirements........................................................................................................................................50

Ongoing Requirements .............................................................................................................................................................50

Affordability Period.......................................................................................................................................................50

Recapture Option ..........................................................................................................................................................51

Resale Option .................................................................................................................................................................51

Enforcing Resale and Recapture Provisions..............................................................................................................53

Low-Income Targeting .................................................................................................................................................53

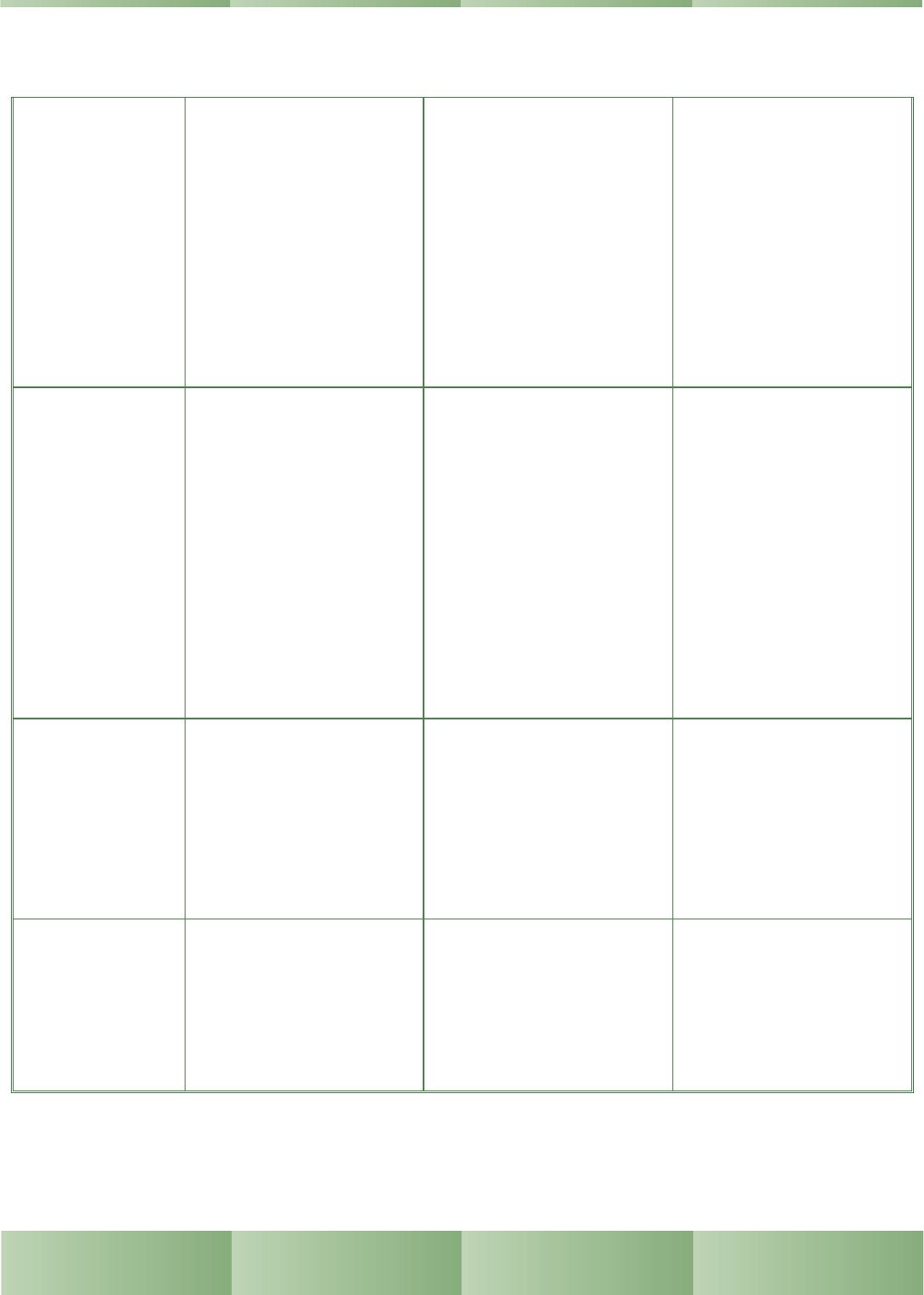

3-1: American Dream Downpayment Initiative (ADDI)—Side-By-Side Comparison of Downpayment Assistance

Requirements—By Source of Funds ......................................................................................................................................55

Chapter 4: Using HOME and CDBG for Homeowner Rehabilitation....................................................................................57

Approaches to Homeowner Rehabilitation...........................................................................................................................57

Minor Rehabilitation......................................................................................................................................................57

Moderate/Substantial Rehabilitation ..........................................................................................................................57

Reconstruction ...............................................................................................................................................................58

Historic Preservation.....................................................................................................................................................59

Lead-based Paint Hazard Evaluation and Reduction ..............................................................................................59

Code Enforcement ........................................................................................................................................................60

Home-based Business Rehabilitation .........................................................................................................................61

Financing and Undertaking Homeowner Rehabilitation.....................................................................................................61

Partners............................................................................................................................................................................61

Forms of Financial Assistance .....................................................................................................................................61

Eligible Costs..................................................................................................................................................................64

Property and Rehabilitation Standards .......................................................................................................................65

HOME and CDBG

Initial Owner Incomes ..................................................................................................................................................66

Other Federal Requirements........................................................................................................................................67

Chapter 5: Using HOME and CDBG for Comprehensive Neighborhood Revitalization ...................................................68

Approaches to Neighborhood Revitalization........................................................................................................................68

Planning Models for Urban Redevelopment.............................................................................................................68

Housing Assistance........................................................................................................................................................69

Property Inspections and Code Enforcement ..........................................................................................................69

Infrastructure Development and Improvement .......................................................................................................70

Economic Development...............................................................................................................................................70

Community Facilities and Public Services ................................................................................................................. 71

Financing and Requirements for Neighborhood Revitalization ........................................................................................71

Partners............................................................................................................................................................................71

Approaches to Financing..............................................................................................................................................72

Eligible Costs..................................................................................................................................................................74

Chapter 6: Making Strategic Investment Decisions ..................................................................................................................... 75

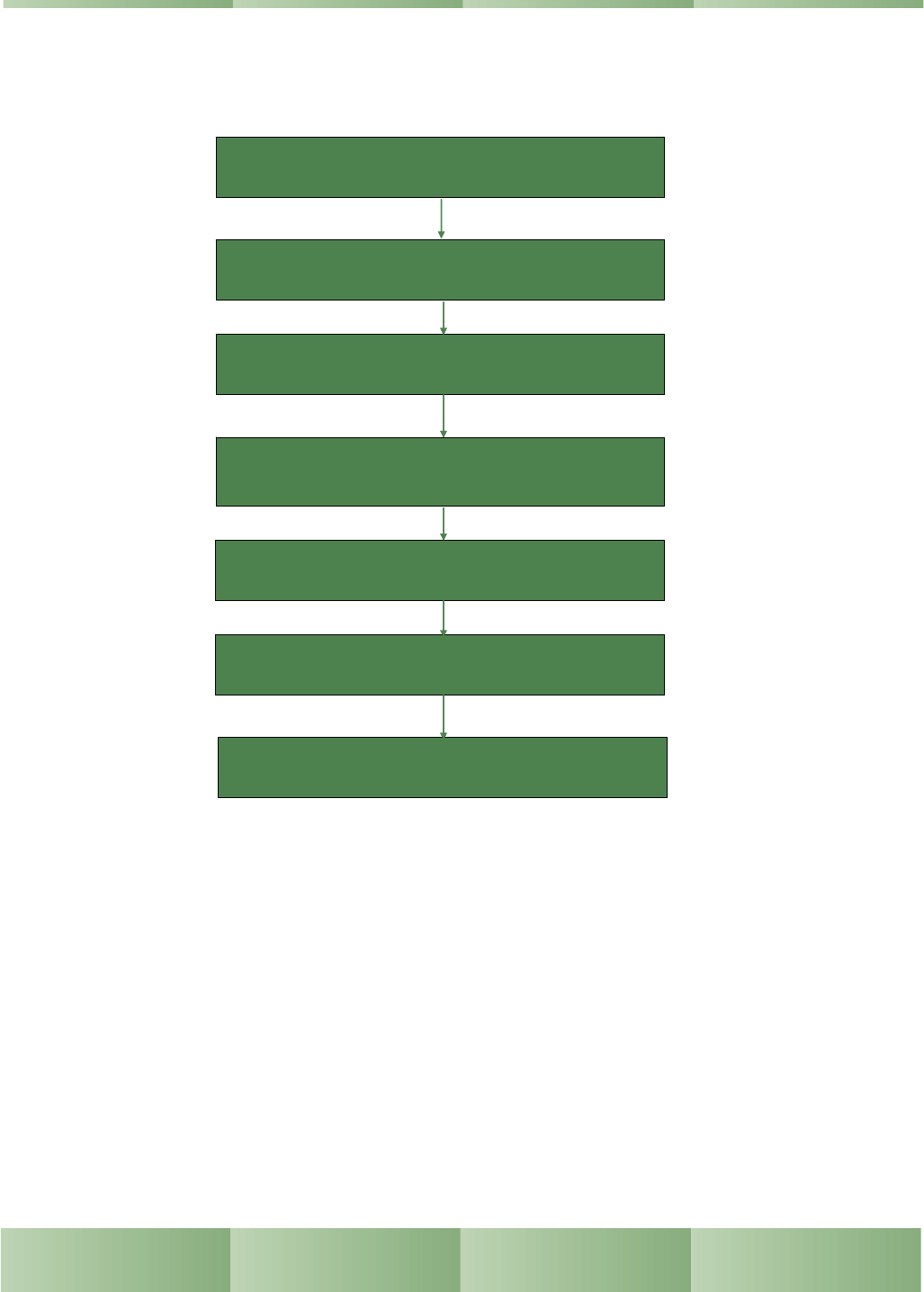

Step 1: Evaluate community needs and preferences...............................................................................................76

Step 2: Determine program types based upon needs and preferences ................................................................77

Step 3: State intended program outcomes ................................................................................................................78

Step 4: Evaluate the strengths of HOME and CDBG v. intended outcomes.................................................... 78

Step 5: Assess CDBG and HOME constraints .......................................................................................................80

Step 6: Determine whether program should be co-funded with HOME and CDBG...................................... 81

Step 7: If co-funded program, evaluate each project to determine appropriate uses of funds ........................82

Administering Programs ...........................................................................................................................................................83

Choosing Projects and Partners .................................................................................................................................. 83

Setting Up Adequate Financial Systems .................................................................................................................................85

Developing Efficient Reporting and Record Keeping Systems .........................................................................................86

Reviewing Program Performance and Compliance ............................................................................................................. 87

Endnotes ..............................................................................................................................................................................................90

iii

HOME and CDBG

Introduction

Two programs form the cornerstone of the U.S.

Department of Housing and Urban Development’s

(HUD’s) community development efforts—the

HOME Investment Partnerships Program and the

Community Development Block Grant (CDBG).

Across the country, HOME and CDBG funds are

helping communities develop new affordable housing

for both renters and homebuyers, rehabilitate existing

homes, and turn around troubled neighborhoods.

While HOME and CDBG share the same goals—the

growt

h and improvement of America’s communities—

the programs differ in important ways. For example,

HOME and CDBG have different eligible activities,

different approaches to meeting the needs of low- and

moderate-income families, and different rules regarding

matching funds.

By using HOME and CDBG funds strategically,

com

munities can optimize their use of both funding

sources, while working within the limitations and

regulations of both programs.

HOME and CDBG: Working Together to Create Affordable

Housing

is the community development professional’s

guide to using HOME and CDBG funds for affordable

housing activities as strategically as possible. This

model program guide begins by outlining how HOME

and CDBG work and by identifying critical differences

between the two programs. Next, the guide provides a

detailed consideration of how to use HOME and

CDBG to support rental housing, homeownership,

rehabilitation, and comprehensive neighborhood

revitalization projects, giving special attention to how

to coordinate the two funding sources. The guide

concludes with some final considerations for making

strategic investment decisions using HOME and

CDBG.

Throughout the guide, the discussion will focus on the

impo

rtance of using program resources effectively, and

how this can be done to meet local housing and

community development needs, and to stay in

compliance with Federal program rules.

Making Effective Use of

Program Resources

Community development is a broad term that

encompasses a wide range of activities, including

housing, economic development, health, employment

and educational services, infrastructure, and many other

activities designed to improve the welfare of

neighborhoods and families. In towns, counties, and

states across America, community development

remains a primary concern for local leaders, the staffs

of nonprofit and public agencies, and citizens alike.

Yet, Federal resources for community development are

limited and are not sufficient to

address all of the needs

in most jurisdictions. While HOME and CDBG can

play an important part in addressing community

development needs, they must be used wisely in order

to obtain the maximum benefit from each resource. It

is important that jurisdictions use these programs

strategically because:

• Some t

ypes of activities are better suited to be

undertaken under one program than the other;

• Whe

n combining these resources within projects, it

is important that the rules for each program be

followed; and

• Effective lev

eraging of CDBG and HOME

resources can mean a generating a greater “bang for

the buck” than when each program is used alone.

Selecting Suitable Activities

When Congress enacted the CDBG and HOME

Programs, it had differing objectives in mind. CDBG

was created to consolidate a number of previous

categorical grant programs that had addressed a range

of community needs, including water and sewer, urban

renewal, model cities, historic preservation, and

neighborhood development. CDBG’s eligible

1

HOME and CDBG

activities, therefore, are diverse and range from

residential rehabilitation to infrastructure to public

services. While it has a strong focus on meeting the

needs of low-income persons, it is also designed to be

flexible in order to address other concerns.

The HOME Program was created nearly two decades

later,

to address the growing affordable housing crisis

in America. Its purpose is to increase the supply of

affordable housing for low-and very low-income

households. There are four eligible activities under

HOME and all relate directly to affordable housing. In

addition, HOME has a secondary purpose of

supporting the development and sustainability of

nonprofit housing providers. To achieve this, it

mandates that a percentage of each annual allocation be

used by community housing development

organizations (CHDOs) to own, develop, or sponsor

housing.

Given these differing legislative histories and program

purp

oses, it is no wonder that each program has its

relative strengths and limitations. For example,

CDBG cannot generally be used to construct new

housing. However, it can be used to develop the

infrastructure in a low-income neighborhood that

might support a new affordable housing development.

HOME, on the other hand, can be a very good

resource for building new units but cannot be used to

create off-site infrastructure. So, making strategic

choices about how the HOME and CDBG programs

are used can help a jurisdiction address a wide range of

needs within its available resources.

In addition to these programmatic constraints, there are

also str

ategic elements in deciding which program to

use for which purpose.

Assume, for example, that the goal of a jurisdiction’s

progr

am is to improve and preserve its supply of

affordable homebuyer units. Both CDBG and HOME

can be used to assist with homeownership. However, only

HOME mandates that units remain affordable for a

specific period of time. HOME might be the preferred

resource to use in this situation.

Now assume a different a jurisdiction wishes to spur

neighborhoo

d revitalization by rehabilitating rental units.

Its objective is not necessarily to create long-term

affordability, but rather to address the blight in the area

so that other businesses and homeowners will locate in the

neighborhood. In this instance, both HOME and

CDBG can be used for rental rehabilitation. However,

CDBG

might be the preferred resource because it does not

mandate long-term affordability restrictions and allows for

undertaking projects where the focus is not necessarily on

addressing the needs of low- and moderate-income

households but rather on cleaning up a blighted

neighborhood.

Jurisdictions that are familiar with the rules and

flexibiliti

es of both HOME and CDBG will be able to

make strategic choices about investing their program

resources.

Complying with the Rules

In addition to thinking strategically about how and

when to use HOME and CDBG, jurisdictions need to

ensure that both sets of program rules are met. When

the programs are operated separately and are not

combined in projects, jurisdictions must make sure that

they carefully document compliance for each program

according to the rules established by the CDBG and

HOME regulations.

However, CDBG and HOME are sometimes

combined in a single project. When

this is done, the

jurisdiction must ensure that both sets of rules are met

simultaneously. Since both HOME and CDBG are

Federal programs with implementing statutes and

regulations, neither program overrules the other. In

other words, the most stringent applicable requirement

from each program must always be met.

For example, when a PJ invests HOME funds in a

multifamily rental project, it can elect to invest its

resources in selected HOME units. That is, if the

jurisdiction wishes to partially rehabilitate a 10-unit

rental building, it can fund two HOME units and

leverage other funds to rehabilitate the remaining eight

units. However, if CDBG is also invested in that same

10-unit project, the entire structure is considered to be

assisted. Therefore, if the housing national objective is

used it would mandate that at least 51 percent of the

units be occupied by low- and moderate-income

households, regardless of the amount of CDBG assistance

in the project. Under HOME rules, only the two

assisted units would need to be occupied by income-eligible

families, but CDBG mandates that low- or moderate-

income families occupy at least six units.

So, it is important for the jurisdiction to understand the

rules of b

oth programs in order to be sure that all

activities are compliant.

2

HOME and CDBG

Leveraging CDBG and HOME

Jurisdictions need to be familiar with how CDBG and

HOME work together so that they can get the greatest

impact for their investments. As noted above, there

are differing instances when either CDBG or HOME is

the most appropriate tool for a particular task at hand.

However, sometimes when those tools are used

together, the impact is greater than either could achieve

alone.

For example, assume that HOME funds are used to

support ho

meownership in a given neighborhood.

HOME or CDBG can provide downpayment assistance

to help low-income families to finance the purchase of new

homes in a targeted neighborhood. However, if the

families move into the neighborhood and find that the

community lacks community facilities and local retail

shops to meet their needs, it might make sense for the

jurisdiction to invest its CDBG funds in the non-housing

needs of the neighborhood, and its HOME funds in the

homeownership program. This way, it can stretch its

resources to undertake a broader range of activities to

meet the diverse needs of the neighborhood residents. This

results in a more vibrant, successful community.

It is important for jurisdicti

ons to consider how CDBG

and HOME can work together so that they are able to

get the greatest return for their programs.

Planning for CDBG and

HOME

There are numerous ways that CDBG and HOME can

be combined. Jurisdictions need to evaluate these

options and then make decisions about how to

effectively use these programs given the needs of their

community. The section below provides a brief

summary of how jurisdictions can consider these

options as a part of their planning processes. For

more detail on the key steps in making strategic

decisions regarding CDBG and HOME funding, see

Chapter 6 of this guidebook.

To tackle these complex program decisions,

jurisdictions

may wish to consider developing:

• An assessment of commu

nity needs;

• A community-wide plan for addressing needs

thr

ough an array of different community

development projects; and

• A clearl

y-defined approach to each individual

community development project.

Assessment of Community Needs

Although many American communities share similar

challenges, such as a lack of affordable housing, no two

communities are exactly alike. A needs assessment

helps each community identify and define its individual

needs as well as its strengths and assets.

The needs assessment should be co

nducted by the local

or state government and should be the first step in

determining how to effectively use HOME and CDBG

resources. Often this assessment is done as a part of

the Consolidated Planning process and includes:

• A descripti

on of the assets and resources present in

the community (such as a community college or

existing infrastructure);

• Curren

t data and projections concerning

demographics (e.g., households, income levels, etc.)

as well as housing supply and demand;

• Data on rents

and housing prices in specific

neighborhoods within the jurisdiction;

• An a

nalysis of the health of the local economy;

• An assessment of the state of the jurisdiction’s

infras

tructure;

• An a

nalysis of which neighborhoods have the most

acute community development needs; and

• A general revi

ew of the feasibility and need for

certain types of community development projects

(such as infill housing versus multifamily rental

housing) in specific neighborhoods.

Community-Wide Plan

After conducting a community needs assessment,

community development staff should develop a plan

for tackling the challenges faced by the community.

Typically, the plan will involve a number of different

community development activities in different

neighborhoods within the jurisdiction. The plan strives

to coordinate different types of housing, economic

development, infrastructure, and related activities to

maximize the impact of public funds.

States and localities can use the Co

nsolidated Planning

process—a requirement for direct grantees receiving

HOME or CDBG funds—as an opportunity to

undertake community-wide planning. Note that

3

HOME and CDBG

subrecipients and units of general local government

who receive funds from a direct HUD grantee do not

need to do their own consolidated plan. They are

covered by the grantee’s plan. This planning process

ensures that there is input from nonprofit partners,

local businesses, and most importantly, residents that

will be affected by community development projects.

Wide community participation in the planning process

is invaluable because it ensures that community

development projects truly reflect what the community

wants and needs.

When preparing the Consolidated Plan and Annual

Action Plan, jurisdictions determine the appropriate

level and nature of a variety of housing activities, such

as the development of local rental, homebuyer,

rehabilitation, special needs, or other types of

affordable housing programs to address community

needs. The process should also address how HOME

and CDBG can be used strategically to address the

needs identified for the community.

Individual Project Approach

With a consolidated plan in hand, jurisdictions are

ready to evaluate the feasibility, implementation and

benefits of program resources for each individual

project.

Feasibility Research. Often, communities will need

additional research to establish the feasibility of a given

project. For housing projects, a market study is a

focused assessment of whether a specific housing

product, on a specific site, will be able to attract

residents with the ability to pay—and how quickly.

This type of study will explicitly conclude whether the

proposed rents or housing prices for the specific

project are achievable. For neighborhood

revitalization projects, a broader market study that

examines both housing and economic data may be

necessary to assess the feasibility of a larger, multi-

faceted initiative.

Implementation Planning. As early as possible,

community development staff should identify the

potential costs and existing concerns related to the

implementation of the project. Even an apparently

straightforward housing development project can

involve a diverse array of costs: administrative

expenses, infrastructure modifications, services for

residents, basic construction costs, and more. As this

model will explain in detail, the availability of HOME

and CDBG funds (as well as other sources of financial

support) depends on whether the specific use of funds

qualifies as an eligible activity under their respective

program rules. Strategic use of program funds can

maximize the impact of subsidies while meeting the

eligibility requirements of all relevant programs.

Costs and Benefits of Funding Sources. Subsidies

from HOME and CDBG programs enable

communities to undertake projects that may not

otherwise be feasible. However, it is important to

consider the additional responsibilities and restrictions

that come with using these funds for particular

projects. Some possible responsibilities and restrictions

include, depending on the funding source:

• Rent limits for subsidized units;

• Restrictions on the purchase and resale of

subsidized homes;

• Rep

orting and monitoring responsibilities to ensure

ongoing compliance with program rules and

regulations; and

• Rules regarding the targeting of subsidies toward a

program’s intended beneficiaries.

Communities should consider carefully how the

requirements of different funding sources will impact a

given project.

How to Use this Model

This model program guide is intended for PJ staff to

help communities use their HOME and CDBG funds

strategically. The guide is designed to be a useful

“crash course” in the programs and it highlights the

differences that help practitioners invest these

resources wisely. Each chapter describes the applicable

program rules for each specific type of housing

development—rental housing, homeownership, and

rehabilitation—and includes a side-by-side comparison

of the key requirements of the HOME and CDBG

programs. This format should assist the community

development practitioner in need of specific

programmatic information for quick-reference.

This guide is organized in the following six chapters:

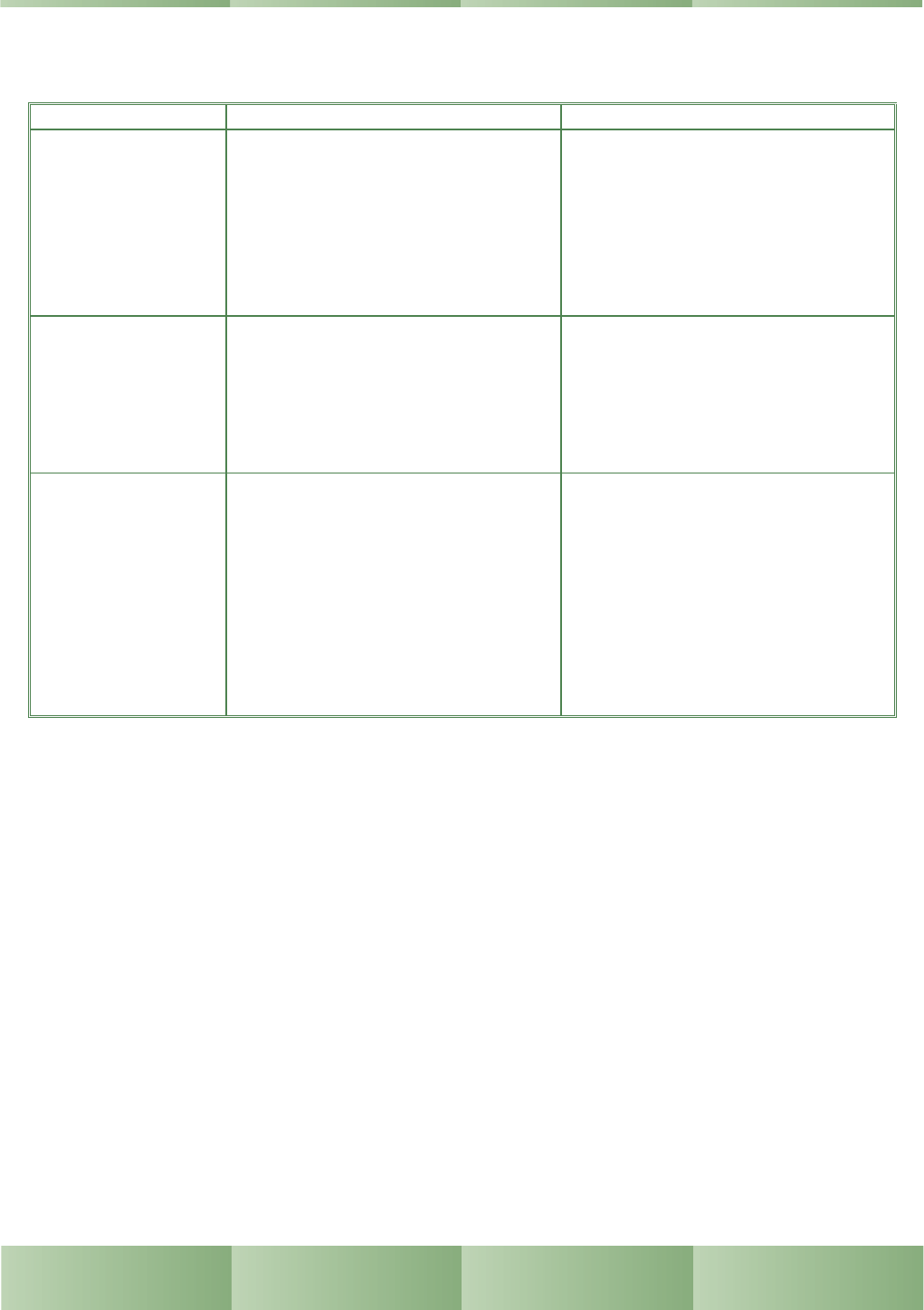

Chapter 1: HOME and CDBG Basics introduces

each program and provides general information on the

eligible activities, program restrictions, and

administrative requirements for each program. The

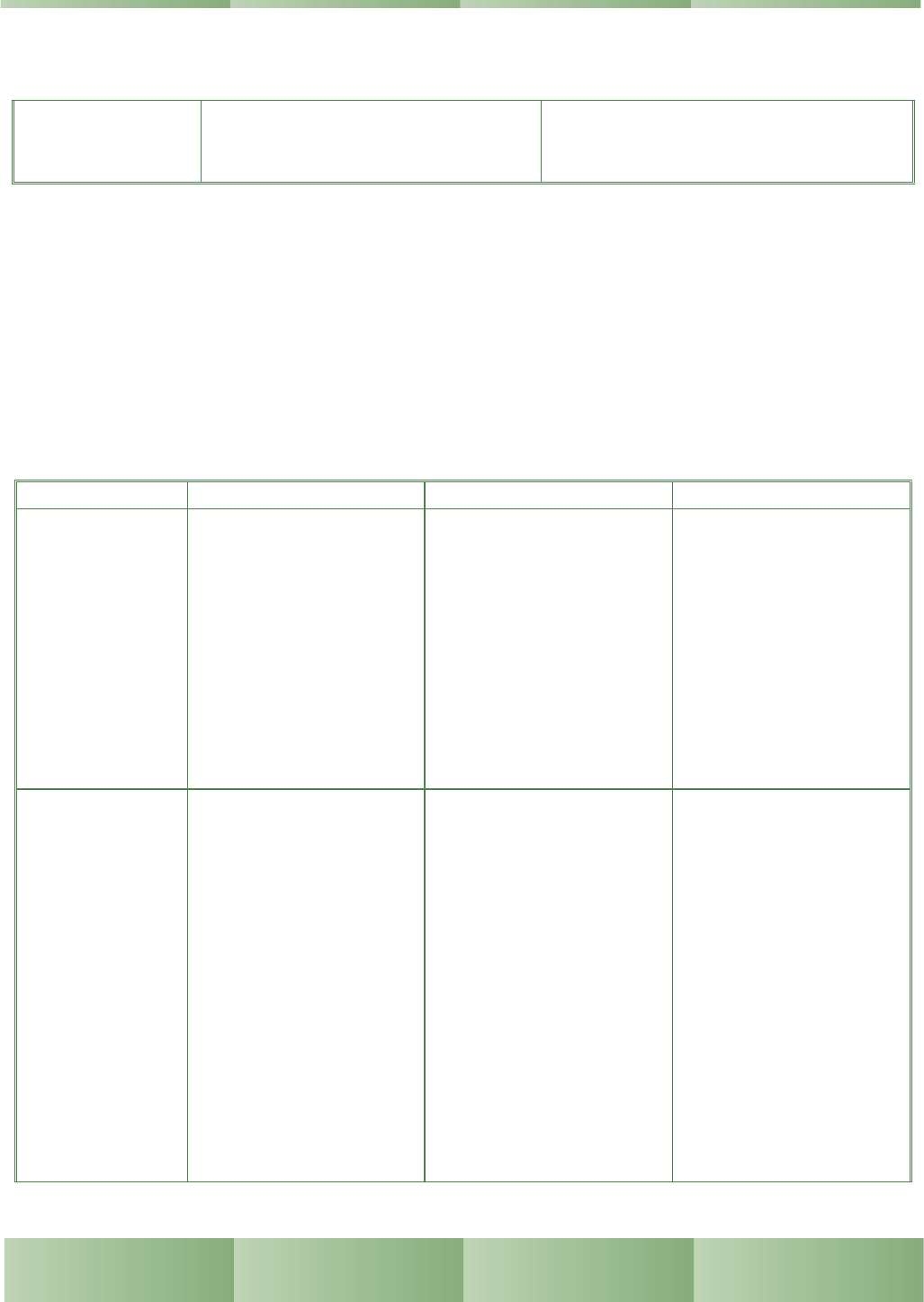

chapter includes a chart that summarizes the key

program requirements to facilitate comparison.

4

HOME and CDBG

Chapter 2: Using HOME and CDBG for Rental

Housing describes rental housing requirements and

illustrates how HOME and CDBG can be combined to

support the development of affordable rental housing.

Chapter 3: Using HOME and CDBG for

Homeownership Programs explores ways to assist

homebuyers and considers the most effective ways that

communities combine the two programs to develop

housing units for purchase.

Chapter 4: Using HOME and CDBG for

Homeowner Rehabilitation provides an analysis of

using HOME and CDBG for homeowner

rehabilitation.

Chapter 5: Using HOME and CDBG for

Comprehensive Neighborhood Revitalization

considers the use of HOME and CDBG funds for

targeted community development within a specific

neighborhood. Strategic use of HOME and CDBG

along with other resources can allow communities a

chance to breathe new life into a deteriorating

neighborhood.

Chapter 6: Making Strategic Investment

Decisions focuses on how communities can make the

most of every subsidy dollar. Careful allocation of

program funds, effective program design, and program

performance review are all part of an effective use of

HOME and CDBG.

Under the HOME Program, the recipient of HUD

funds is known as a “participating jurisdiction” or “PJ.”

Under the CDBG program, the recipient is known as a

“grantee.” Throughout this guidebook, the general

term “jurisdiction” will be used to mean the local or

5

HOME and CDBG

state government that receives HOME or CDBG

funds. When specifically referring solely to the

recipient of HOME funds, “PJ” will be used and when

specifically referring solely to the recipient of CDBG

funds, “grantee” will be used. Under the State CDBG

Program, units of general local government that receive

CDBG money from a state are sometimes known as

“state grant recipients”. Under this guide they will be

called units of general local government.

In addition, the guide uses the expression “low- and

moderate-income” or “LMI” to refer to income-eligible

persons or households under both HOME and CDBG.

This is because persons or households who are at or

below 80 percent of area median income, as

determined and adjusted by HUD on an annual basis,

are called “LMI” under the CDBG program, and “low-

income” under the HOME Program. When the guide

discusses the CDBG or HOME requirements of one of

the programs specifically, it uses the terminology of

that particular program.

About the Model Program

Guides

HOME and CDBG: Working Together to Create Affordable

Housing is one of a series of model program guides

published by the Office of Affordable Housing

Programs of the U.S. Department of Housing and

Urban Development. The model program guide series

provides technical assistance and guidance on HOME

Program implementation to participating jurisdictions.

Model program guides are available to the public at no

cost. For more information about the model program

guides, see the Office of Affordable Housing

Programs’ online library at

http://www.hud.gov/offices/cpd/affordablehousing/

library/modelguides/index.cfm.

Chapter 1:

HOME and CDBG Basics

This chapter is a basic primer for housing practitioners who are new to the HOME or CDBG programs. It provides a general

overview of the two programs, including their statutory intents and key program partners. For each program, the chapter describes

basic eligible activities and highlights important administrative requirements. The subsequent chapters provide more detail on each of

the eligible affordable housing activities. This chapter concludes with a detailed chart that compares the key requirements of the two

programs.

Part 1: HOME Investment

Partnerships (HOME)

Program

What is HOME?

Created by the National Affordable Housing Act of

1990 (NAHA), HOME is the largest Federal block

grant available to communities to create affordable

housing. The intent of the HOME Program is to:

• Increase the supply of decent, affordable housing to

low- and very low-i

ncome households;

• Expa

nd the capacity of nonprofit housing

providers;

•

Streng

then the ability of state and local

governments to provide housing; and

• Leverag

e private sector participation.

Every y

e

ar, the U.S. Department of Housing and

Urban Develo

pment (HUD) determines the amount of

HOME funds that states and local governments—also

known as Participating Jurisdictions (PJs)—are eligible

to receive using a formula designed to reflect relative

housing need. After money has been set aside for

America’s insular areas

i

and for nationwide HUD

technical assistance, the remaining funds are divided

between states (40 percent) and units of general local

government (60 percent).

The HOME Program regulations are found at 24 CFR

Part 92. The Final Rule was published on September

16, 1996 and was amended on March 30, 2004 to include

ADDI. The HOME regulations may be found on HUD’s

Office of Affordable Housing Programs website at:

http://www.hud.gov/offices/cpd/affordablehousing/

lawsandregs/regs/home/index.cfm

HOME Program Partners

To ensure success in providing affordable housing

opportunities, the HOME Program requires PJs to

establish new partnerships and maintain existing

partnerships. Partners play different roles at different

times, depending upon the project or activity being

undertaken with HOME funds. Key program partners

include:

• PJs. A PJ is any state, local government,

or

consortium that has been designated by HUD to

administer a HOME program.

¾ State governmen

ts: States are given broad discretion

in administering HOME funds. They may

allocate funds to units of local government

directly, evaluate and fund projects themselves,

or combine the two approaches. States may also

fund projects jointly with local PJs. They may

use HOME funds anywhere within the state,

including within the boundaries of local PJs.

¾ Local governm

ents and consortia: Units of general

local government, including cities, towns,

townships, and parishes, may receive PJ

designation or they may be allocated funds by

the state. Contiguous units of local government

may form a consortium for the purpose of

qualifying for a direct allocation of HOME

funds. The local government or consortium

then administers the funds for eligible HOME

uses.

• Community Housing Development

Organizations (CHDOs

). A CHDO is a private,

nonprofit organization that meets a series of

qualifications prescribed in the HOME regulations.

Each PJ must use a minimum of 15 percent of its

annual allocation for housing that is owned,

developed, or sponsored by CHDOs. PJs evaluate

6

HOME and CDBG

organizations’ qualifications and designate them as

CHDOs. CHDOs also may be involved in the

program as subrecipients, but the use of HOME

funds in this capacity is not counted towards the 15

percent set-aside.

• Subrecipients. A subrecipient is a public agency or

nonprofit organization selected by a PJ to

administer all or a portion of its HOME program.

It may or may not also qualify as a CHDO. A

public agency or nonprofit organization that

receives HOME funds solely as a developer or

owner of housing in not considered a subrecipient.

Other important partners in the HOME Program

include:

• Developers, owners and sponsors. Developers,

owners, and sponsors of housing developed with

HOME funds may be for-profit or nonprofit

entities. Developers are the entities responsible for

the putting the housing deal together. Owners are

the entities that hold title to the property after

rehabilitation, construction, or acquisition.

Sponsors work with other organizations—such as

other nonprofits—to assist them to develop and

own housing. At project completion, they turn over

title to the property to the other organization.

• Private lenders. Most HOME projects leverage or

involve other financing, from for-profit lenders or

other entities such as foundations or community

groups.

• Third-party contractors. There is a range of other

entities that might work on the HOME Program,

such as architects, planners, construction managers,

real estate agents, or consultants. These third-party

contractors are responsible for specific, well-defined

tasks that contribute to the PJ’s overall affordable

housing activity, such as consolidated planning.

HOME Program Activities

HOME funds can be used to support four general

affordable housing activities:

• Homeowner rehabilitation. HOME funds may be

used to assist existing owner-occupants with the

repair, rehabilitation, or reconstruction of their

homes.

• Homebuyer activities. PJs may finance the

acquisition and/or rehabilitation, or new

construction of homes for homebuyers.

• Rental housing. Affordable rental housing may be

acquired and/or rehabilitated, or constructed.

• Tenant-based rental assistance (TBRA).

Financial assistance for rent, security deposits and,

under certain conditions, utility deposits may be

provided to tenants. Assistance for utility deposits

may only be provided in conjunction with a TBRA

security deposit or monthly rental assistance

program.

Eligible Costs

Eligible costs under the HOME Program depend on

the nature of the program activity. Generally, HOME

funds can be used for the following activities:

• New construction. HOME funds may be used for

new construction of both rental and ownership

housing. Any project that includes the addition of

dwelling units outside the existing walls of a

structure is considered new construction.

• Rehabilitation. This includes the alteration,

improvement, or modification of an existing

structure. It also includes moving an existing

structure to a foundation constructed with HOME

funds. Rehabilitation may include adding rooms

outside the existing walls of a structure, but adding a

housing unit is considered new construction.

• Reconstruction. This refers to rebuilding a

structure on the same lot where housing is standing

at the time of project commitment. HOME funds

may be used to build a new foundation or repair an

existing foundation. Reconstruction also includes

replacing a substandard manufactured house with a

new manufactured house. During reconstruction,

the number of rooms per unit may change, but the

number of units may not.

• Conversion. Conversion of an existing structure

from another use to affordable residential housing is

usually classified as rehabilitation. If conversion

involves additional units beyond the walls of an

existing structure, the entire project is new

construction. Conversion of a structure to

commercial use is not eligible under HOME.

• Site improvements. Site improvements must be in

keeping with improvements to surrounding

7

HOME and CDBG

standard projects. They include new, on-site

improvements where none are present or the repair

of existing infrastructure when it is essential to the

development. Building new, off-site utility

connections to an adjacent street is also eligible.

Otherwise, off-site infrastructure is not eligible as a

HOME expense, but may be eligible for match

credit.

• Acquisit

ion of property. Acquisition of existing

standard property, or substandard property in need

of rehabilitation, is eligible as part of either a

homebuyer program or a rental housing project.

After acquisition, rental units must meet HOME

rental occupancy, affordability, and lease

requirements.

• Acquisition

of vacant land. HOME funds may be

used for acquisition of vacant land only if

construction will begin on a HOME project within

12 months of purchase. Land banking is

prohibited.

• Demolition. Demolition of an existing structure

may be funded through HOME only if construction

will begin on the HOME project within 12 months.

• Relocation costs. The Un

iform Relocation

Assistance and Real Property Acquisition Policies

Act of 1970 (known as the “Uniform Relocation

Act” or “URA”) and Section 104(d) of the Housing

and Community Development Act of 1974, as

amended (known as “Section 104(d)”) apply to

HOME-assisted properties. Both permanent and

temporary relocation assistance are eligible costs,

for all those relocated, regardless of income. Staff

and overhead costs associated with relocation

assistance are also eligible. Note that

homeownership undertaken with FY04 –FY07

American Dream Downpayment Initiative (ADDI)

funds is not subject to the URA.

• Refinanc

ing. HOME funds may be used to

refinance existing debt on single family, owner-

occupied properties in connection with HOME-

funded rehabilitation. The refinancing must be

necessary to reduce the owner’s overall housing

costs and make the housing more affordable.

Refinancing for the purpose of taking out equity is

not permitted. HOME may be used to refinance

existing debt on multifamily projects being

rehabilitated with HOME funds, if refinancing is

necessary to permit or continue long-term

affordability, and is consistent with PJ-established

refinancing guidelines, as outlined in the PJ’s

consolidated plan.

• Capitalization of project reserves. HOME funds

may

be used to fund an operating deficit reserve for

rental new construction and rehabilitation projects

for the initial rent-up period. The reserve may be

used to pay for project operating expenses,

scheduled payments to a replacement reserve, and

debt service for a period of up to 18 months.

• Project-related soft costs.

These must be

reasonable and necessary. Examples of eligible

project soft costs include:

¾ Fina

nce-related costs;

¾

¾

¾

¾

¾

Architectural, engineering, and related

professional services;

Tenant and homebuyer counseling, provided the

recipient of counseling ultimately becomes the

tenant or owner of a HOME-assisted unit;

Projec

t audit costs;

Affirmative marketi

ng and fair housing services

to prospective tenants or owners of an assisted

project; and

PJ staff c

osts directly related to projects (not

including TBRA).

Prohibited Activities and Costs

HOME funds may not be used to support the

following activities and costs:

• Project reserve accounts.

HOME funds may not

be used to provide project reserve accounts (except

for initial operating deficit reserves) or to pay for

operating subsidies.

• Tenant-based rental assistance for certain

purposes. H

OME funds may not be used for

certain mandated existing Housing Choice Voucher

Program (formerly known as Section 8) uses, such

as Housing Choice Voucher rent subsidies for

troubled HUD-insured projects.

• Match for other Federal progra

ms. HOME

Program funds may not be used as the “nonfederal”

match for other Federal programs except to match

McKinney Act funds.

8

HOME and CDBG

• Development, operations, or modernization of

public housing:

¾ HOME funds cannot be used alone or in

conjunction with HUD-funded public housing

program funds (e.g., Public Housing capital

programs such as Development, Comprehensive

Improvements Assistance Program (CIAP) or

Comprehensive Grant Program (CGP)) to

acquire, rehabilitate, or construct public housing

units.

¾ HOME funds cannot be used to operate public

housing units under any circumstances.

• Properties receiving assistance under 24 CFR

Part 248 (Prepayment of Low-Income Housing

Mortgages). Properties receiving assistance

through the Low-Income Housing Preservation and

Resident Homeownership Act (LIHPRHA) or the

Emergency Low-Income Preservation Act

(ELIHPA) are not eligible for HOME assistance

except if the HOME assistance is provided to

priority purchasers. Note: these programs are no

longer funded by HUD.

• Double-d

ipping. During the first year after

project completion, the PJ may commit additional

funds to a project. After the first year, no additional

HOME funds may be provided to a HOME-

assisted project during the relevant period of

affordability, except that:

¾

¾

¾

Tenant based rental assistance to families may be

renewed.

Tenant based rental assistance may be provided

to families that will occupy housing previously

assisted with HOME funds.

A homebuyer

may be assisted with HOME

funds to acquire a unit that was previously

assisted with HOME funds.

• Acquisit

ion of PJ-owned property. A PJ may not

use HOME Program funds to reimburse itself for

property in its inventory or property purchased for

another purpose. However, in anticipation of a

HOME project, a PJ may use HOME funds to:

¾

¾

Acquire property; and

Reimburse itself for property acquired with

other funds, specifically for a HOME project.

• Project-ba

sed rental assistance. HOME funds

may not be used for rental assistance if receipt of

funds is tied to occupancy in a particular project.

Funds from another source, such as Housing

Choice Voucher, may be used for this type of

project-based assistance in a HOME-assisted unit.

Further, HOME funds may be used for other

eligible costs, such as rehabilitation, in units

receiving project-based assistance from another

source—for example, Housing Choice Voucher or

state-funded project-based assistance.

• Pay for delin

quent taxes, fees, or charges.

HOME funds may not be used to pay delinquent

taxes, fees, or charges on properties to be assisted

with HOME funds.

HOME Program

Requirements

The HOME Program is designed to provide affordable

housing to low-income and very low-income families

and individuals. Therefore, the program has some key

restrictions that are designed to foster HUD’s

commitment to long-term affordable housing, quality

units and reasonable costs. These key restrictions are

discussed below.

Income Eligibility and Verification

Beneficiaries of HOME funds—homebuyers,

homeowners or tenants—must be low-income or very

low-income. “Low-income” is defined as an annual

income that does not exceed 80 percent of area median

income, as adjusted by household size. “Very low-

income” is defined as having an annual income that

does not exceed 50 percent of area median income, as

adjusted by household size. A household’s income

eligibility is determined based on its annual income.

Annual income is the gross amount of income

anticipated by all adults in the household during the 12

months following the effective date of the

determination. To calculate annual income, the PJ may

choose among three definitions of income:

• Section 8 annual (gross)

income. Annual income

determinations are based on the Part 5 definition of

annual income. Note that this definition is now

known as Part 5.

9

HOME and CDBG

• IRS adjusted gross income. The calculation for

“adjusted gross income” outlined in the Federal

income tax IRS Form 1040.

• Census long form annual income. Annual

income is defined as annual income used for the

Census long form, for the most recent decennial

Census.

Having the flexibility to choose the definition of

income facilitates the combination of HOME with

other funds, from sources that use differing definitions

of income. The PJ’s choice of definition may depend

on the other sources of funds in a project. For

example:

• The Community Development Block Grant

(CDBG) Program allows the same three definitions

of income; therefore, projects with both sources

should use the same definition.

• The Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC)

Program requires the use of the Part 5 definition of

income; therefore, projects that use both HOME

and LIHTCs can use the Part 5 definition and

comply with the requirements of both programs.

Subsidy Limits

HOME establishes minimum and maximum amounts

of HOME funds that may be invested in any project.

The minimum amount of HOME funds is $1,000

multiplied by the number of HOME-assisted units in

the project. The minimum

only

relates to the HOME

funds, and

not

to any other funds that might be used

for project costs. The minimum HOME investment

does not apply to TBRA.

The maximum per-unit HOME subsidy limit varies by

PJ. HUD determines the maximum amounts, which

are based on the PJ’s Section 221(d)(3) program limits

for the metropolitan area, each year. As above, those

limits apply only to HOME funds and not other funds

that may be invested in the project. These limits are

available from the HUD Field Office, or information

can be found online at

http://www.hud.gov/offices/cpd/affordableho

using/programs/

home/limits/subsidylimits.cfm.

The maximum per-unit subsidy limit is:

• 100 percent

of the dollar limits for a Section

221(d)(3) nonprofit sponsor, elevator-type

development, indexed for base city high cost areas,

and adjusted for the number of bedrooms.

• For some PJs, the 221(d)(3

) limit has already been

increased to 210 percent of the base limit. For

these PJs, HUD will allow, upon request, an

increase in the per-unit subsidy amount on a

program-wide basis. However, the absolute

maximum subsidy limit that HUD will allow is 240

percent of the base 221(d)(3) limits.

Affordability Periods

To ensure that HOME investments yield affordable

housing over the long term, HOME imposes rent and

occupancy requirements over the length of an

affordability period. For homebuyer and rental

projects, the length of the affordability period depends

on the amount of HOME assistance to the project or

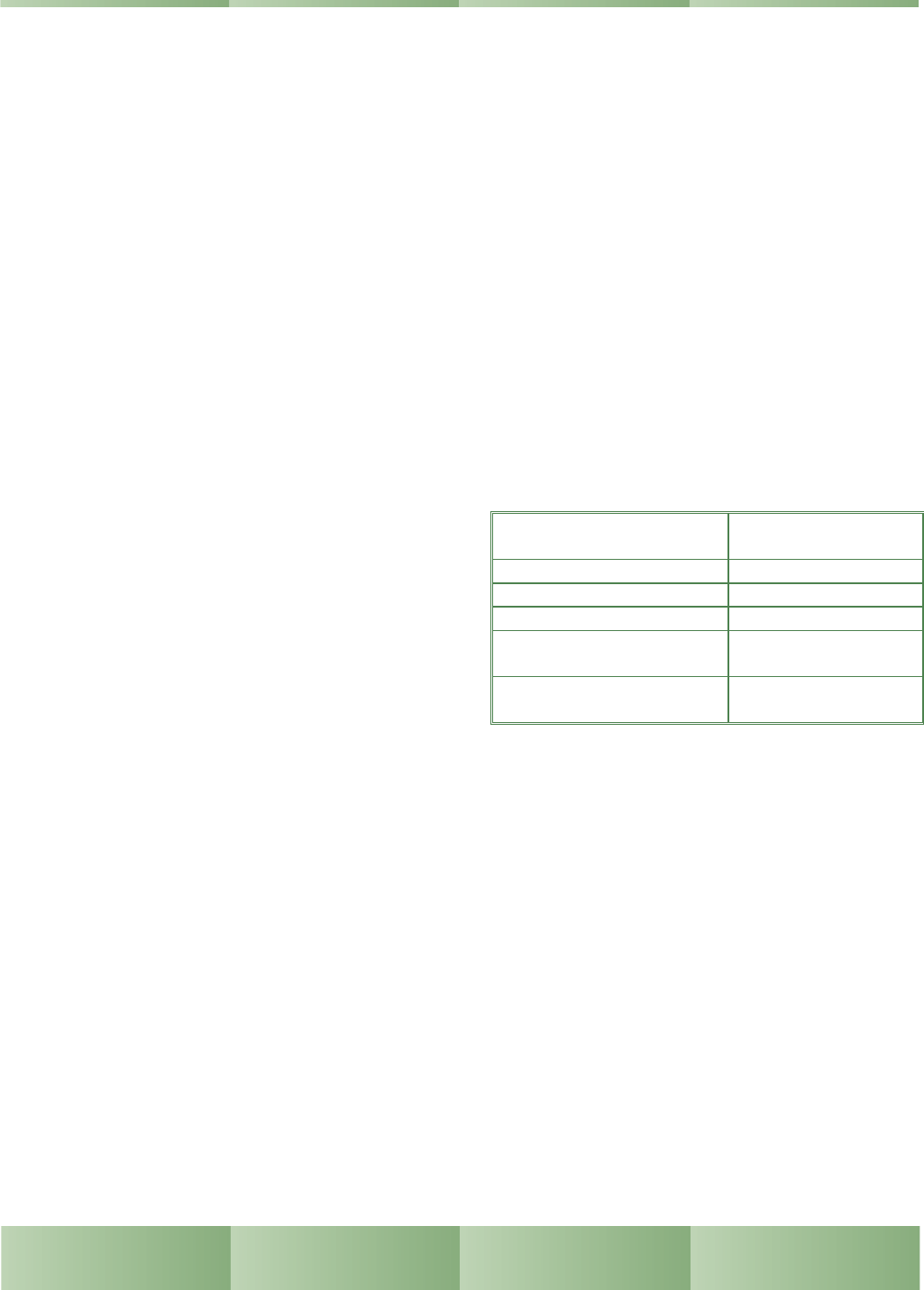

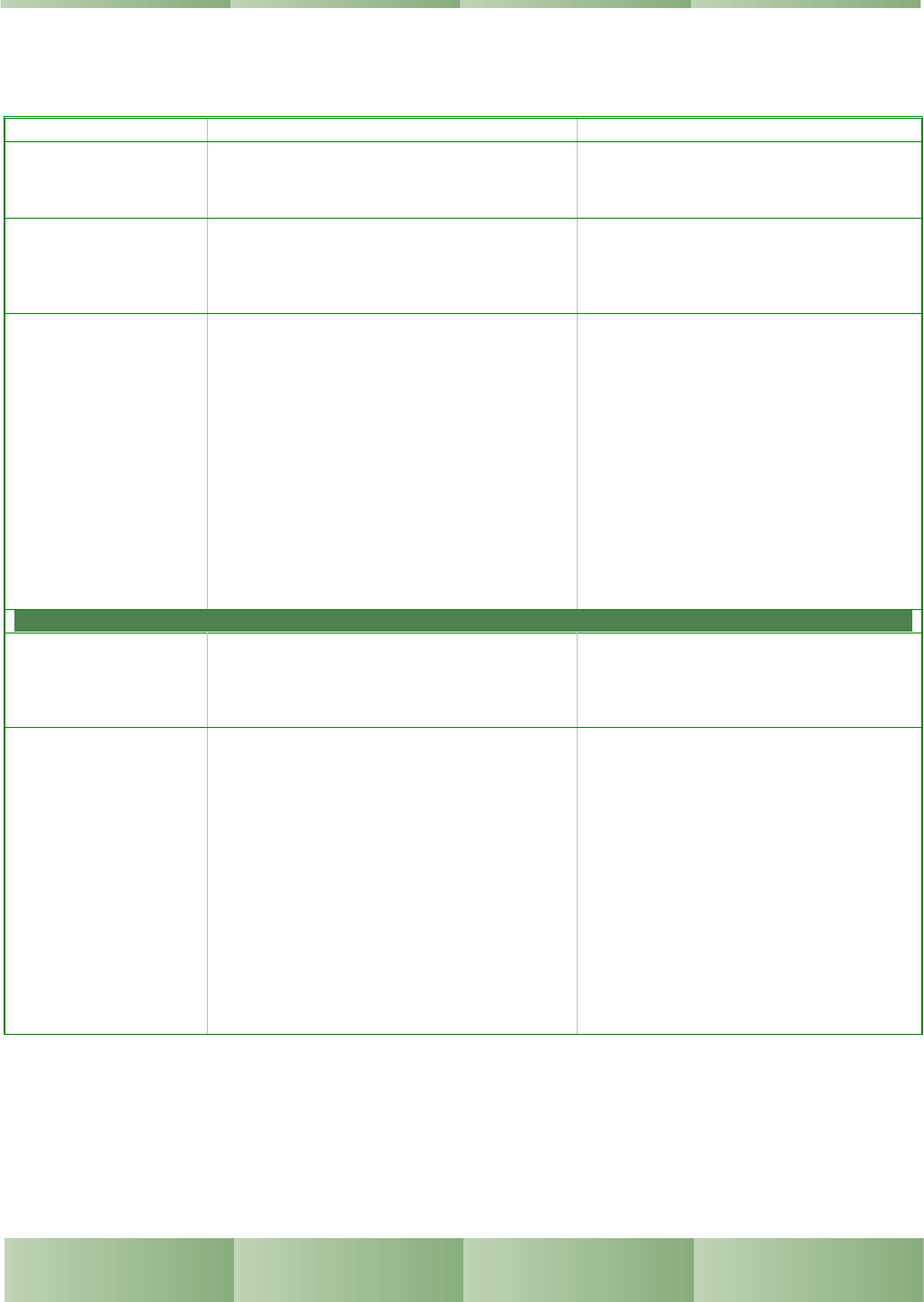

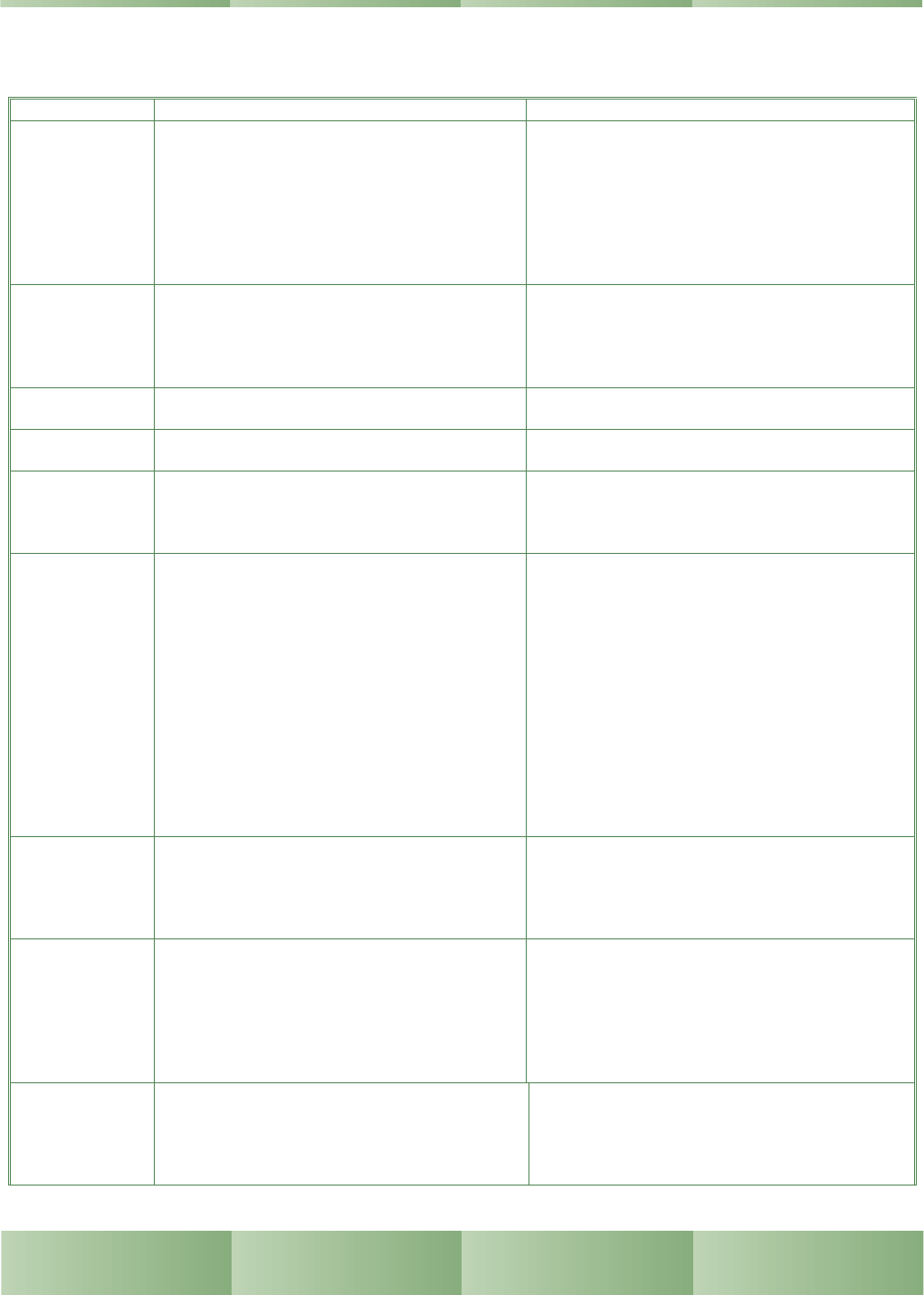

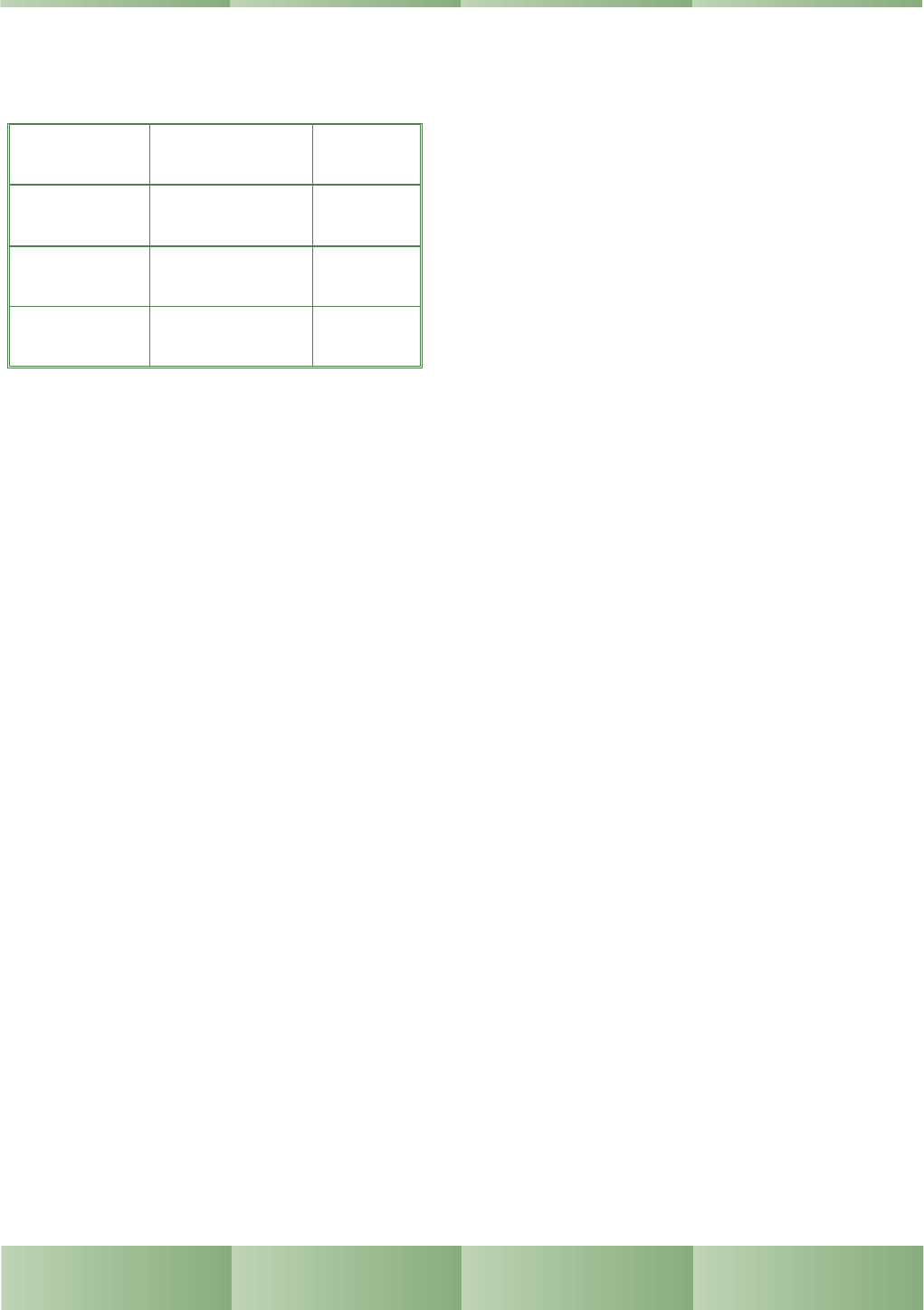

buyer, and the nature of the activity funded. Table 1-1

provides the affordability periods.

Table 1-1: Determining the HOME

Period of Affordabil

ity

HOME Assistance per

Unit or

Buyer

Length of the

Affordability Period

Less than $15,000 5 years

$15,000 - $40,000 10 years

More than $40,000 15 years

New construction of rental

housing

20 years

Refinancing of rental

housing

15 years

Throughout the affordability period, income-eligible

households must occupy the HOME-assisted housing.

• Rental housing. When units become vacant

during the affordability period, subsequent tenants

must be income eligible and must be charged the

applicable HOME rent.

• Homebuyer assistance. If a home purchased with

HOME assistance is sold during the affordability

period, resale or recapture provisions apply to

ensure the continued provision of affordable

homeownership.

Maximum Value

HOME investments are for modest housing. Thus,

HOME imposes maximum value limits on owner

occupied and homebuyer units. The maximum

purchase price may not exceed 95 percent of the

median purchase price of homes purchased in the area.

In the case of a purchase-rehabilitation project, the

10

HOME and CDBG

value of the property after rehabilitation may not

exceed 95 percent of the area median purchase price

for that type of housing. The after-rehabilitation value

estimate should be completed prior to investment of

HOME funds.

There are two options that PJs have for determining

the 95 percent of the median purchase price. Most PJs

opt to use the FHA Section 203(b) Mortgage Limits.

These limits are available online at

http://www.hud.gov/offices/cpd/affordablehousing/programs/

home/limits/maxprice.cfm.

PJs also have the option of conducting a specialized

market analysis that meets certain requirements

established by HUD. (These can be found in the

HOME Final Rule at 24 CFR 92.254 (a)(2)(iii).)

Property Standards

HOME-funded properties must meet certain minimum

property standards.

• State and local standards. State and local codes

and ordinances apply to any HOME-funded project

regardless of whether the project involves

acquisition, rehabilitation, or new construction.

• Model codes. For rehabilitation or new

construction projects where there are not state or

local building codes, the PJ must use one of three

national model codes.

ii

• Housing quality standards. For acquisition-only

projects, if there are no state or local codes or

standards, the PJ must enforce Housing Choice

Voucher Housing Quality Standards (previously

Section 8 HQS).

• Rehabilitation standards. Each PJ must develop

written rehabilitation standards to apply to all

HOME-funded rehabilitation work. These

standards are similar to work specifications, and

generally describe the methods and materials to be

used when performing rehabilitation activities.

HOME Administrative

Requirements

Administrative and Planning Costs

Each PJ may use up to 10 percent of each year’s

HOME allocation for reasonable administrative and

planning costs. In addition, up to 10 percent of

program income deposited in a PJ’s local HOME

account during a program year may be used for

administrative and planning costs. PJs, state recipients

and subrecipients may incur administrative and

planning costs.

Eligible administrative and planning costs include

expenditures for salaries, wages, and related costs of PJ

staff persons responsible for HOME Program

administration. In addition to staff salaries and related

costs, other planning and administrative costs could

include:

• Goods and services necessary for administration

(for example, utilities, office supplies, etc.);

• Administrative services under third party

agreements (for example, legal services);

• Administering a tenant-based rental assistance

(TBRA) program;

• Providing public information;

• Fair housing activities;

• Indirect costs under a cost allocation plan prepared

in accordance with applicable Office of

Management and Budget (OMB) Circular

requirements;

• Preparation of the Consolidated Plan; and

• Complying with other Federal requirements.

Match

The HOME Program requires that PJs contribute an

amount equal to no less than 25 percent of the total

HOME funds drawn down for project costs as a

permanent contribution to affordable housing. PJs

incur a match obligation only for project funds, not for

11

HOME and CDBG

administrative, operating, or capacity building

expenditures. Although the obligation is incurred

based on per dollar expended in project, match credit

can be invested in any HOME-eligible project, whether

the project receives HOME funds or not. Match can

be contributed in many different forms, including cash;

value of waived taxes or fees; value of donated land or

property; donated goods, services, materials or

equipment.

Commitment and Expenditure

Deadlines

The HOME Program encourages PJs to expend their

affordable housing funds expeditiously by imposing

two deadlines. HOME funds for a given program year

must be committed to a HOME project within two

years of signing the HOME Investment Partnerships

Agreement. For the CHDO set-aside funds, PJs must

reserve funds for use by CHDOs within that 24-month

period. In addition, HOME funds must be expended

within five years of receipt of funds. The Integrated

Disbursement and Information System (IDIS) tracks

each PJ’s progress toward meeting these deadlines.

Failure to meet these deadlines may result in a return of

HOME funds to HUD.

Program Income

Program income is the income received by a PJ, state

recipient, or subrecipient directly generated from the

use of HOME funds or matching contributions.

Program income must follow all of the HOME rules

and must be used before drawing down new HOME

funds. Program income includes, but is not limited to:

• Proceeds from the sale or long-term lease of real

property acquired, rehabilitated, or constructed with

HOME funds or matching contributions;

• Income from the use or rental of real property

owned by a PJ, state recipient or subrecipient that

was acquired, rehabilitated, or constructed with

HOME funds or matching contributions, minus the

costs incidental to generating that income;

• Payments of principal and interest on loans made

with HOME or matching funds, and proceeds from

the sale of loans or obligations secured by loans

made with HOME or matching contributions;

• Interest on program income; and

• Any other interest or return on the investment of

HOME and matching funds.

All HOME program income must be used in

accordance with the HOME Program rules. Where

program income is concerned, there is an important

distinction between subrecipients/state recipients and

CHDOs. Specifically:

• Program income received by subrecipients or state

recipients, such as rental income, repayment of

loans, interest on loans, fees, and payments for

services, is considered program income subject to

HOME regulations.

• However, project proceeds received and retained by

CHDOs are not considered program income. PJs

have the option of permitting project proceeds to

be retained by CHDOs or they may require

CHDOs to return these proceeds to the PJ. If the

project proceeds are returned to the PJ, they are

program income. Use of funds must be specified in

the CHDO written agreement and limited to either

HOME-eligible activities or other housing activities

that benefit low-income families.

Pre-Award Costs

PJs may incur eligible costs prior to the effective date

of their annual HOME Investment Partnerships

Agreement, subject to certain conditions. Both

administrative and project costs may be incurred. Only

costs eligible under the HOME Program rules in effect

at the time the costs are incurred are included.

Expenditures must meet all regulatory requirements,

including environmental review regulations.

Pre-award project costs may not exceed 25 percent of

the current HOME grant without written approval

from HUD. PJs may authorize subrecipients and state

recipients to incur pre-award costs, but authorization

must be in writing. Citizen participation and all other

applicable HOME requirements must be met.

12

HOME and CDBG

Part 2: Community

Development Block Grant

(CDBG Program)

What is CDBG?

Authorized under Title I of the Housing and

Community Development Act of 1974 (HCDA), as

amended, the Community Development Block Grant

(CDBG) is an annual grant to localities and states to

assist in the development of viable communities.

These viable communities are achieved by providing

the following, principally for persons of low- and

moderate-income:

• Decent housing;

• A suitable living environment; and

• Expanded economic opportunities.

“Principally” means that, at a minimum, 70 percent of

the CDBG funds expended by a state or entitlement

grantee should be used to benefit low- and moderate-

income people. This 70 percent can be measured over

the course of a one-, two- or three-year time period,

selected by the grantee.

Every year, each city in a metropolitan area with at least

50,000 people, principal cities (designated by OMB) of

metropolitan areas, and each county with more than

200,000 in population (excluding metropolitan cities

therein) receive CDBG funds. These cities and urban

counties are called “entitlement grantees”—they are

entitled to CDBG by virtue of their size. Each state

also receives a CDBG grant. The CDBG grant

amounts are determined by the higher of two formulas:

• U.S. Census data based on overcrowded housing,

population, and poverty; or

• U.S. Census data based on age of housing,

population growth lag, and poverty.

Entitlement communities receive the largest portion of

CDBG funding (70 percent) and states receive the

other 30 percent. Each state receives CDBG to pass

along to its smaller towns and rural counties (non-

entitlement communities), which usually compete with

one another for the funds. Every state has its own

procedures for operating the CDBG Program.

The CDBG regulations can be found at 24 CFR Part

570. Information about the Entitlement Program and

its regulations are found at:

http://www.hud.gov/offices/cpd/

communitydevelopment/

programs/entitlement/index.cfm

.

Under the State CDBG Program, states follow the

HCDA as supplemented by the State CDBG

regulations, as applicable. In exercising its obligation to

review a state’s performance under the program, HUD

gives maximum feasible deference to the state’s

interpretation of these statutory and regulatory

requirements. HUD will accept the state’s

interpretations, provided these are not clearly

inconsistent with the Act or the regulation.

Information about the State CDBG Program and its

regulations can be found at the following website:

http://www.hud.gov/offices/cpd/

communitydevelopment/

programs/stateadmin/index.cfm

.

CDBG Program Partners

The CDBG Program relies primarily on several key

partners to plan and implement eligible program

activities. These partners include:

• CDBG Grantee. In the Entitlement Program, local

governments are known as grantees. In the State

CDBG Program, the state is the grantee.

• Unit of General Local Government (UGLG). In

the State CDBG program, a unit of general local

government is the community funded by the state

to undertake CDBG activities. It is always a local

government such as a town, county, or village. In

the State CDBG Program, these are often referred

to as state grant recipients.

• Subrecipient. A subrecipient is a nonprofit or

public entity that assists the grantee to implement

and administer all or part of its CDBG Program.

Subrecipients are generally public or private

nonprofit organizations that assist the grantee to

undertake a series of activities, such as

administering a home rehabilitation loan pool.

Public agencies that are not a part of the grantee’s

legal government entity can also be subrecipients,

such as a water and sewer authority.

• Community-Based Development Organization

(CBDO). CBDOs are organizations that undertake

13

HOME and CDBG

CDBG-funded activities as part of a neighborhood

revitalization, energy conservation, or community

economic development project. CBDOs can be

nonprofit or some for-profit organizations, but