Adultspan Journal Adultspan Journal

Volume 14 Issue 1 Article 5

4-1-2015

Archetypal Identity Development, Meaning in Life, and Life Archetypal Identity Development, Meaning in Life, and Life

Satisfaction: Differences Among Clinical Mental Health Satisfaction: Differences Among Clinical Mental Health

Counselors, School Counselors, and Counselor Educators Counselors, School Counselors, and Counselor Educators

Suzanne Degges-White

Kevin Stoltz

Follow this and additional works at: https://mds.marshall.edu/adsp

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Degges-White, Suzanne and Stoltz, Kevin (2015) "Archetypal Identity Development, Meaning in Life, and

Life Satisfaction: Differences Among Clinical Mental Health Counselors, School Counselors, and

Counselor Educators,"

Adultspan Journal

: Vol. 14: Iss. 1, Article 5.

Available at: https://mds.marshall.edu/adsp/vol14/iss1/5

This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted

for inclusion in Adultspan Journal by an authorized editor of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please

contact [email protected].

Archetypal Identity Development, Meaning in Life, and Life Satisfaction: Archetypal Identity Development, Meaning in Life, and Life Satisfaction:

Differences Among Clinical Mental Health Counselors, School Counselors, and Differences Among Clinical Mental Health Counselors, School Counselors, and

Counselor Educators Counselor Educators

Keywords Keywords

professional counselor identity, archetypes, meaning in life, life satisfaction

This research article is available in Adultspan Journal: https://mds.marshall.edu/adsp/vol14/iss1/5

ADULTSPAN Journal April 2015 Vol. 14 No. 1 49

© 2015 by the American Counseling Association. All rights reserved.

Received 10/21/14

Revised —

Accepted 10/22/14

DOI: 10.1002/j.2161-0029.2015.00036.x

Archetypal Identity Development,

Meaning in Life, and

Life Satisfaction:

Differences Among Clinical

Mental Health Counselors, School

Counselors, and Counselor Educators

Suzanne Degges-White and Kevin Stoltz

Adults pursuing careers in counselor education, clinical mental health counsel-

ing, and counselor education (N = 256) participated in a study that examined

relationships among archetypal identity development, meaning in life, and

life satisfaction. Significant differences between groups existed for 5 archetypal

identities, and meaning in life was significantly related to life satisfaction.

Keywords: professional counselor identity, archetypes, meaning in life,

life satisfaction

Counseling professionals are frequently drawn to the field because they want

to “help people.” Motivated by altruism, counselors are in a unique position

in which they fulfill their own professional desires through the provision of

service to others. The professional identity development process counselors

experience is dynamic by nature, but in this study we explore whether there

are core identity differences among clinical mental health counselors, school

counselors, and counselor educators.

The identity development process of counselors has been referred to as

an individuation process (Auxier, Hughes, & Kline, 2003; Bruss & Kopala,

1993; Skovholt & Ronnestad, 1992) in which counselors must relinquish

their reliance on external experts and develop a sense of personal mastery and

capability regarding the profession. According to Borders and Usher (1992),

counselor identity development is continuous and lifelong, and it reflects a

Suzanne Degges-White, Department of Leadership and Counseling, University of Mississippi; Kevin

Stoltz, Department of Leadership Studies, University of Central Arkansas. Suzanne Degges-White is now

at Department of Counseling, Adult and Higher Education, Northern Illinois University. Correspondence

concerning this article should be addressed to Suzanne Degges-White, Department of Counseling, Adult

and Higher Education, Northern Illinois University, 300 Normal Road, 200 Gabel Building, DeKalb, IL

60115 (e-mail: sdeggeswhite@niu.edu).

ACAASPAN_v14_n1_0415TEXT.indd 49 2/9/2015 8:47:28 AM

1Published by Marshall Digital Scholar, 2015

50 ADULTSPAN Journal April 2015 Vol. 14 No. 1

deeper shift in personal identity, awareness, and behavior than other careers.

Moss, Gibson, and Dollarhide (2014) noted that counselors’ professional

identity development actually reflects an integration of the personal self and

professional self that results in a unique, personalized professional identity.

Thus, the individual identity initially brought to the profession by a counselor

may potentially exert a significant and continuing influence on professional

accomplishments and experiences. As the core conditions of counseling in-

clude an emphasis on the practitioner’s genuineness and congruence (Rogers,

1957), the initial personal identity of the counselor holds extreme significance

in the shaping of the professional identity over the course of development

(Gibson, Dollarhide, & Moss, 2010). Thus, a closer examination of personal

identity may be valuable.

ARCHETYPE THEORY

Carl Jung (1875–1961) is credited with the development of archetype theory,

which provides a framework for understanding one’s own seemingly innate behav-

ioral patterns as well as one’s responses to others’ behavior (Jung, 1964, 1968). In

essence, archetypes are the internal prototypes, or models, that people hold of a

basic character, as in a story, that elicit specific emotional responses. For instance,

the Jester is an archetype that may play out the role of keeping others entertained

and, perhaps, distracted from unpleasant events at hand (Pearson & Marr, 2002).

In other milieus, such as an alcoholic household, the Jester may be the mascot,

cheerleader, or clown (Wegscheider, 1981). Archetypal patterns are assumed to

reflect the unconscious, and they resonate at deep emotional levels with others.

As Jung (1964) first developed his initial archetype theory, he framed these

types as residing within the collective unconscious. The collective unconscious

refers to that knowledge held by an individual that has not been gained through

the personal experiences of that individual. Jung (1936/1959) proposed that

the collective unconscious is hereditary in nature and that it holds the patterns

of instinctual behavior that are virtually universal across cultures. It is these

primordial behavior patterns that are activated to give life to archetypal personi-

fication. As Jung (1967) noted, “An image can be considered archetypal when

it can be shown to exist in the records of human history, in identical form and

with the same meaning” (p. 273).

Faber and Mayer (2009) explored neo-archetypal theory, which purports

that individuals can identify and categorize people, characters, and experiences

within an archetypal framework. This theory aligns with that of researchers and

theorists (Campbell, 1949; Pearson & Marr, 2002) who presented a description

of archetypes as being “key elements in a common language” (Faber & Mayer,

2009, p. 307). Sharing an awareness of the various players in culture allows

one to enjoy the plays of Shakespeare as well as the latest thriller or celebrity

drama. Furthermore, one’s own personal archetypal identity of the moment may

ACAASPAN_v14_n1_0415TEXT.indd 50 2/9/2015 8:47:28 AM

2

https://mds.marshall.edu/adsp/vol14/iss1/5

DOI: -

ADULTSPAN Journal April 2015 Vol. 14 No. 1 51

actually influence how one responds to a cultural archetype or to an individual

displaying what might be termed archetypal behavior.

Another area of exploration of archetypes and personalities was addressed by

McPeek (2008). McPeek explored the relationship between archetype identities

as measured by the Pearson-Marr Archetype Indicator (PMAI), personality types

as measured by the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), and self-reported

global stress levels. McPeek found predictable relationships between many of

the variables (e.g., high-scoring Jesters experienced significantly less stress than

low-scoring Jesters) supporting the concepts and validity of the PMAI. The

current study extends, in some ways, these earlier studies as it explores career

choice and its relationship, if any, to archetypal identity.

THE WOUNDED HEALER

Although the Wounded Healer is not an archetype included among the 12 ar-

chetypes in the PMAI, it is often referenced in literature related to the helping

professions, including counseling (Hartwig Moorhead, Gill, Barrio Minton,

& Myers, 2012; Kern, 2014; Meekums, 2008; Moodley, 2010; Trusty, Ng, &

Watts, 2005). Woundedness refers to damage that may have been inflicted on an

individual in any number of ways, including emotionally, spiritually, physically,

intellectually, and sexually. Wounded Healers refer to helping professionals who

have wrestled with and, ideally, overcome past experiences in which they were

wounded themselves. It has been suggested that the experience of having been

wounded in the past may enhance an individual’s ability to offer empathy and

compassion for others (Bennet, 1979; Stone, 2008).

The literature on the Wounded Healer construct is mixed in terms of the

value and influence of woundedness for healers. Some studies have suggested

that having experienced and integrated personal emotional wounds from the

past has a positive effect on skill development and performance (e.g., Trusty et

al., 2005). These experiences are seen as contributing to counselor effective-

ness. Other studies (e.g., Hartwig Moorhead et al., 2012) have suggested that

woundedness, for some counselors-in-training, may need to be an area of focus

in terms of how it influences both professional development and effectiveness.

We designed the current study to assess whether the Wounded Healer construct

resonates personally for participants from each of three areas of professional focus:

clinical mental health counseling, school counseling, and counselor education.

MEANING IN LIFE AND LIFE SATISFACTION

Archetypal identity has been explored in relation to other global personality

traits in the past. McPeek (2008) sought to determine whether personality

type (as measured by the MBTI) predicted archetypal identity, as measured

by the PMAI. He included stress as a variable to determine if an individual’s

ACAASPAN_v14_n1_0415TEXT.indd 51 2/9/2015 8:47:28 AM

3Published by Marshall Digital Scholar, 2015

52 ADULTSPAN Journal April 2015 Vol. 14 No. 1

archetypal identity could predict stress level, based on the described nature of an

archetype. In the current study, measures of meaning in life and life satisfaction

were explored to determine whether relationships existed between these global

assessments, archetypal identity, and career choice in the counseling profession.

A study by Bonebright, Clay, and Ankenmann (2000) exploring life satisfac-

tion among workaholics and nonworkaholics found that workaholics who were

enthusiastic about their careers had higher life satisfaction than nonworkaholics.

This finding suggests that doing something one enjoys and about which one

feels passionate, regardless of how taxing one might perceive it to be, can lead

to significant satisfaction overall. In terms of passion and commitment to pro-

fessional pursuits, many counseling professionals enter the field to fulfill what

they believe to be a vocational calling (Hall, Burkholder, & Sterner, 2013). A

calling to a profession implies that a person’s desire to follow a particular career

is influenced by some force that is perceived as transcendent. This adds a sense

of greater meaning and purpose to the pursuit of a career.

Stoltz, Barclay, Reysen, and Degges-White (2013) discussed occupational

images as a variable in counselor career adjustment. They posited that coun-

selors come to the profession with a specific vision or image that may conflict

with actual work requirements or environments. This can be conceptualized as

the images of the archetype acting in the work environment. Understanding

archetypal images that align with the work responsibilities and tasks should

increase meaning and adjustment to the professional work environment.

Many individuals look to their careers to provide a sense of meaning in their

lives, and Steger and Dik (2009) found that individuals who were seeking meaning

in life exhibited higher levels of global satisfaction if they found meaning in their

careers. In addition, individuals who viewed their careers as a vocational calling,

not just a job, experienced higher levels of meaning in life and life satisfaction

(Steger & Dik, 2009). Duffy and Sedlacek (2010) found that the presence of a

calling in life was correlated with both life satisfaction and meaning in life and that

the search for meaning and the desire for a calling were negatively correlated with

life satisfaction and meaning in life. In this study, we explored the relationships

among meaning in life, life satisfaction, and archetype self-identities.

THE CURRENT STUDY

This study explored archetypal self-identity, meaning in life, and life satisfaction

for individuals within the counseling field. Specifically, we developed the study

to determine if there are differences in these variables between those pursuing

careers in clinical mental health counseling, school counseling, and counselor

education. The following four hypotheses were examined:

Hypothesis 1: The level of identification with the 12 archetypes will significantly

differ between the three professional groups.

ACAASPAN_v14_n1_0415TEXT.indd 52 2/9/2015 8:47:28 AM

4

https://mds.marshall.edu/adsp/vol14/iss1/5

DOI: -

ADULTSPAN Journal April 2015 Vol. 14 No. 1 53

Hypothesis 2: There is a relationship between meaning in life and life satisfac-

tion for counseling professionals.

Hypothesis 3: There will be a significant difference in identification with the

Wounded Healer identity between the groups.

Hypothesis 4: There will be a significant relationship between life satisfaction

and archetype identity within groups.

METHOD

Participants and Procedure

Prior to the collection of data, we received approval for the research from the in-

stitutional review board. A diverse group of adult men and women was recruited

via electronic mailing list announcements that targeted professional counselors,

counselors-in-training, and counselor educators. The survey was completed

electronically using Qualtrics survey software. Of the 313 completed surveys,

256 (82%) respondents qualified as belonging to one of the three categories

under study: clinical mental health counselors (n = 168), school counselors (n

= 35), or counselor educators (n = 53).

The participants were a heterogeneous group in terms of age, ethnicity,

marital status, sexual orientation, religion, and geographical location. Of the

sample, 78.6% were women and 21.4% were men. Approximately a third

(34.5%) of the respondents were in their 20s, 26.1% in their 30s, 17.7% in

their 40s, 12% in their 50s, and 9.6% were 60 or over. The majority (80.3%)

of the respondents were European American, 7.5% were African American,

4.3% were Hispanic, 3.9% were Asian or Pacific Islander, 2.0% were Native

American, and the remaining 2.7% marked “other” as their race. (Percentages

may not total 100 because of rounding.)

Measures

Participants completed three assessments online via Qualtrics. These included

the Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ; Steger, Frazier, Oishi, & Kaler,

2006), the Satisfaction With Life Survey (SWLS; Diener, Emmons, Larsen, &

Griffin, 1985), and the Archetype Self-Identity Questionnaire (ASIQ) based on

the 12 archetype descriptions developed by Faber and Mayer (2009). They also

completed a brief demographic questionnaire that included a single question

that assessed participant identity with the Wounded Healer construct.

MLQ. The MLQ (Steger et al., 2006) was designed to measure two aspects

of meaning in an individual’s life: search for meaning in life and the presence

of meaning in life. The MLQ is composed of 10 items (e.g., “I understand my

life’s meaning,” “I am always looking to find my life’s purpose”), which are rated

on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 = absolutely untrue to 7 = absolutely true. Five

of the 10 items make up the Search for Meaning subscale (MLQ-Search) and

the remaining five the Presence of Meaning (MLQ-Presence) subscale. Internal

consistency of the instrument has been supported by alpha coefficients from

ACAASPAN_v14_n1_0415TEXT.indd 53 2/9/2015 8:47:28 AM

5Published by Marshall Digital Scholar, 2015

54 ADULTSPAN Journal April 2015 Vol. 14 No. 1

.84 to .92 (Steger et al., 2006). The 1-month test–retest stability coefficient

for the MLQ for a sample of undergraduate students was .73. In a review of

the MLQ and similar instruments, Fjelland, Barron, and Foxall (2008) noted

that this measure had both convergent and discriminant validity support. The

two-factor structure of the assessment has also been supported by recent re-

search (Temane, Khumalo, & Wissing, 2014). The Cronbach’s alpha was .70

for the current sample.

SWLS. The SWLS (Diener et al., 1985) was designed to measure individuals’

overall or global satisfaction with their lives. The SWLS is composed of five items

(e.g., “In most ways my life is close to my ideal”), which are rated on a 7-point

scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. The assessment provides a single

measure of global life satisfaction. Internal consistency of the five-item instrument

has been supported by reported alpha coefficients that consistently exceed .80

(Pavot & Diener, 1993). The test–retest reliability for a group of 76 students was

.82 for a 2-month interval (Pavot & Diener, 1993). Pavot and Diener (1993)

also explored the convergent and discriminant validity of the SWLS and found

support for each. Specifically, the SWLS was positively correlated with assessments

of well-being and negatively correlated with assessments of psychological distress.

The Cronbach’s alpha calculated for the SWLS was .88 in the current study.

ASIQ. Using the 12 distinct archetypes explored and described by Pearson

and Marr (2002) and Faber and Mayer (2009), we presented to participants a

brief narrative description of each archetype. The archetypes were Caregiver,

Creator, Everyman/Everywoman, Explorer, Hero, Innocent, Jester, Lover,

Magician, Outlaw, Ruler, and Sage. The descriptions presented to participants

did not include these labels. Participants were asked to indicate their level of

identification with the archetypes’ descriptions on a 5-point scale ranging from

1 = not at all like me to 5 = very much like me. Each item is a discrete measure

of an individual’s self-perceived similarity to a specific, individual type. Owing

to the nature of this instrument, each item is a unique measure in itself.

Data Analyses

Data were analyzed using SPSS 21.1, and an alpha of .05 was set for determining

statistical significance. Descriptive statistics were calculated for all demographic variables

and for scales of the instruments. Pearson product–moment correlation coefficients

and analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were used to examine the research questions.

RESULTS

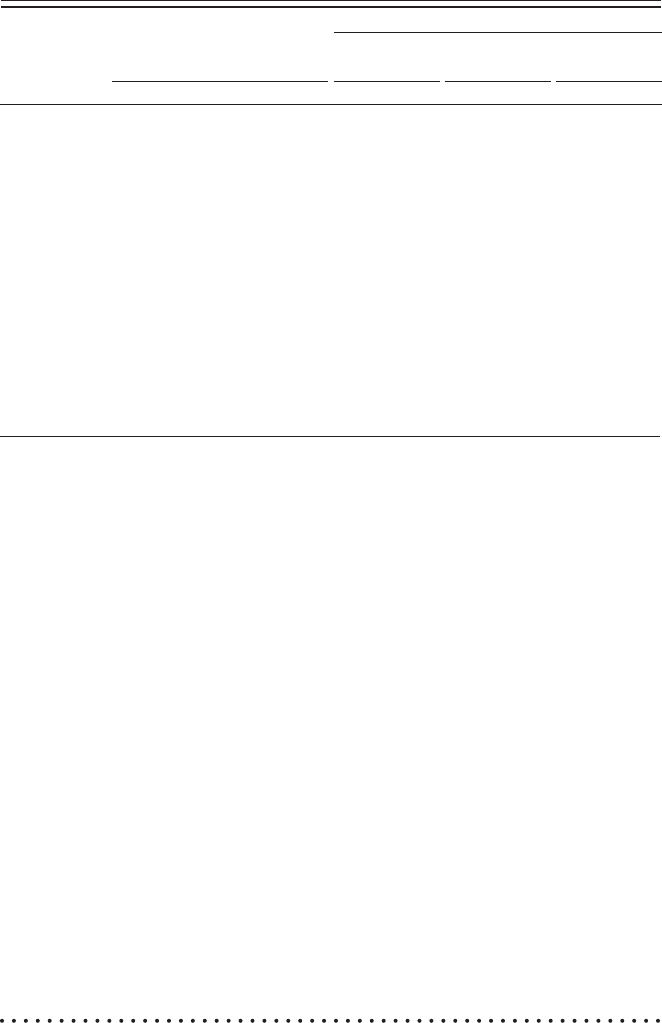

In Table 1, the means; standard deviations; minimum and maximum values

for chronological age and subjective age; and scores on the MLQ, SWLS, and

ASIQ are presented. Participants were divided into three groups on the basis

of their professional path: clinical mental health counselors, school counselors,

and counselor educators.

ACAASPAN_v14_n1_0415TEXT.indd 54 2/9/2015 8:47:28 AM

6

https://mds.marshall.edu/adsp/vol14/iss1/5

DOI: -

ADULTSPAN Journal April 2015 Vol. 14 No. 1 55

Archetype Identity and Professional Focus

We conducted a one-way ANOVA to test the first hypothesis that the level

of identification with a specific archetype varied on the basis of professional

focus. The mean archetype identity scores are presented in Table 1. Significant

relationships at the p < .05 level were found for five of the 12 archetypes. Prior

to further calculations, we ran Levene’s test of homogeneity of variances to de-

termine if any significant differences in variance between groups existed. Two

archetype scales, the Magician and the Sage, were revealed to have significant

differences in variances between groups; therefore, Dunnet’s C rather than

Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) was calculated to explore the

group differences. For the Magician archetype, the Dunnet’s C indicated that

counselor educators had significantly higher scores than either clinical mental

health counselors or school counselors. For the Sage archetype, the Dunnet’s

C indicated that counselor educators had significantly higher scores than

school counselors, but there was no significant difference between counselor

educators and clinical mental health counselors. Although the mean score for

clinical mental health counselors fell between counselor educators and school

TABLE 1

Means and Standard Deviation Scores for

Assessments and Participant Groups

Scale and

Subscale

MLQ

MLQ-P

MLQ-S

SWLS

ASIQ

Caregiver

Creator

E/E

Explorer

Hero

Innocent

Jester

Lover

Magician

Outlaw

Ruler

Sage

WH

M

16.00

10.00

5.00

5.00

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

Total

(N = 256)

SD

Note. CMH = clinical mental health; Couns. Ed. = counselor education; Min. = minimum; Max. =

maximum; MLQ = Meaning in Life Questionnaire; MLQ-P = MLQ Presence of Meaning subscale;

MLQ-S=MLQSearchforMeaningsubscale;SWLS=SatisfactionWithLifeSurvey;ASIQ=

ArchetypeSelf-IdentityQuestionnaire;E/E=Everyman/Everywoman;WH=WoundedHealer.

M SD M SD M SD

Min. Max.

70.00

35.00

35.00

35.00

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

5

4

CMH

(n = 168)

School

(n = 35)

Couns. Ed.

(n = 53)

Professional Focus

53.08

28.63

24.45

25.11

4.58

3.65

3.12

3.75

3.09

3.15

2.69

3.39

3.55

2.75

2.91

3.84

3.09

8.11

4.81

7.13

6.12

0.68

1.14

1.22

1.10

1.22

1.22

1.16

1.22

1.25

1.40

1.22

0.99

0.91

53.40

28.92

24.49

25.10

4.60

3.73

3.11

3.81

3.15

3.25

2.66

3.40

3.47

2.74

2.86

3.87

3.21

8.30

4.71

7.44

6.16

0.69

1.12

1.18

1.09

1.27

1.23

1.18

1.24

1.31

1.37

1.20

0.98

0.89

51.89

27.40

24.49

24.14

4.60

3.11

3.26

3.60

3.00

3.26

3.18

3.50

3.29

2.40

3.17

3.37

2.94

6.83

4.54

7.01

6.20

0.74

1.18

1.29

1.14

1.14

1.20

1.17

1.16

1.29

1.46

1.29

1.14

0.94

52.83

28.53

24.30

25.75

4.53

3.75

3.06

3.62

2.96

2.77

2.49

3.28

3.96

3.02

2.89

4.06

2.79

8.31

5.23

6.30

5.98

0.58

1.13

1.30

1.10

1.11

1.15

1.01

1.21

0.94

1.42

1.25

0.82

0.91

ACAASPAN_v14_n1_0415TEXT.indd 55 2/9/2015 8:47:29 AM

7Published by Marshall Digital Scholar, 2015

56 ADULTSPAN Journal April 2015 Vol. 14 No. 1

counselors, there were no significant differences between clinical mental health

counselors and either of the other two groups.

Tukey’s HSD post hoc calculations were run for the remaining three arche-

types. For the Creator archetype, F(2, 252) = 4.61, p = .011; post hoc compari-

sons using Tukey’s HSD test indicated that the mean scores for clinical mental

health counselors and for counselor educators were each significantly higher

than for school counselors, but scores for clinical mental health counselors and

counselor educators were not significantly different. For the Innocent archetype,

F(2, 253) = 3.27, p = .040; Tukey’s HSD test indicated that there was a signifi-

cant difference only between clinical mental health counselors and counselor

educators, with counselor educators having the lower score. For the Jester ar-

chetype, F(2, 252) = 3.91, p = .21; Tukey’s HSD test indicated that there was

a significant difference in mean scores between school counselors and clinical

mental health counselors as well as school counselors and counselor educators.

School counselors had the highest mean score among the three groups. These

results partially support the first hypothesis that significant differences would

exist based on professional focus.

Meaning in Life and Life Satisfaction

A Pearson product–moment correlation calculated to test the second hypoth-

esis indicated that significant relationships existed between the MLQ subscale

scores and life satisfaction. Results revealed a significant positive relationship

between the MLQ-Presence subscale and life satisfaction (r = .51, R

2

= .26).

These results indicate that the sense of presence of meaning in life accounts for

approximately a quarter of the variance in life satisfaction with this sample. A

significant, negative relationship was found between the MLQ-Search subscale

and life satisfaction (r = –.16, R

2

= .03), indicating that the stronger the search

for meaning, the lower the life satisfaction score. Thus, the second hypothesis

was supported by these findings. Post hoc analysis revealed that there were no

significant differences in either the MLQ or life satisfaction between respondents

based on career focus.

Wounded Healer Identity and Professional Focus

We conducted an ANOVA to determine if there was a difference in the

level of agreement with the statement, “I consider myself to be a ‘Wounded

Healer’ in that I have faced significant personal challenges in my own life.”

The mean scores for agreement with this statement are presented in Table 1

(see row labeled Wounded Healer). Participants responded to this statement

using a 4-point scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree.

There was a significant relationship at the p < .05 level, F(2, 253) = 4.83, p

= .009; Tukey’s HSD test indicated that a significant difference existed be-

tween clinical mental health counselors and counselor educators. The third

hypothesis was partially supported.

ACAASPAN_v14_n1_0415TEXT.indd 56 2/9/2015 8:47:29 AM

8

https://mds.marshall.edu/adsp/vol14/iss1/5

DOI: -

ADULTSPAN Journal April 2015 Vol. 14 No. 1 57

Archetype Identity and Life Satisfaction

We calculated three sets of Pearson product–moment correlations to test the

fourth hypothesis. In the first analysis, we explored the clinical mental health

counselors. For this group, life satisfaction was significantly positively correlated

with scores for the Innocent archetype (r = .20, p < .05) and significantly negatively

correlated with scores for the Outlaw archetype (r = –.25, p < .01). For school

counselors, life satisfaction was significantly positively correlated with scores for

the Hero archetype (r = .53, p < .01). For counselor educators, life satisfaction

was significantly positively correlated with scores for the Caregiver archetype (r

= .29, p < .05) and significantly negatively correlated with scores for the Outlaw

archetype (r = –.39, p < .01). Thus, the fourth hypothesis was supported.

DISCUSSION

This study of 256 adults within the counseling profession was conducted to

explore the relationships between archetype identity, meaning in life, and life

satisfaction. Four hypotheses were put forth, and all four hypotheses were at

least partially supported by the findings. Archetype identity differed significantly

based on respondents’ professional foci for five of the 12 archetypes: Creator,

Innocent, Jester, Magician, and Sage. Having a higher presence of meaning

score was positively related to levels of life satisfaction. Furthermore, a higher

value for the search for meaning score was negatively related to life satisfaction.

Clinical mental health counselors had the highest level of identification with

the Wounded Healer descriptor. Finally, life satisfaction was significantly related

to some of the archetypes for each of the professional foci.

Although the presence of a professional calling was not explored in this

study, it is interesting to note that the Caregiver archetype was endorsed as the

most like participants across all three groups. The Caregiver archetype sug-

gests the presence of altruism and compassion, traits that are often associated

with the perception of a vocational calling (Duffy & Sedlacek, 2010). The

ANOVA data, however, suggest that counselor educators differ from school

counselors by scoring lower on the Jester archetype and higher on the Creator

and Magician archetype. Counselor educators differ from clinical mental health

counselors by scoring higher on the Sage and Magician archetype and lower

on the Innocent archetype. Thus, the results indicate that counselor educators

may possess images of being artistic and creative (Creator) while searching for

enlightenment (Sage) and an understanding of how things work (Magician).

This description shows a high consistency with the Artistic and Investigative

codes from the Holland (1997) coding scheme, intimating that counselor

educators may drive their practice of counseling and counselor education with

both research and artistic traits.

School counselors showed significantly higher scores on the Jester archetype

and lower scores on the Creator archetype. The Jester lives for fun and amuse-

ACAASPAN_v14_n1_0415TEXT.indd 57 2/9/2015 8:47:29 AM

9Published by Marshall Digital Scholar, 2015

58 ADULTSPAN Journal April 2015 Vol. 14 No. 1

ment and is often mischievous and a prankster. In a school setting, focusing on

fun and keeping students positive seem like a good match for this aspect of the

archetype. However, the mischievous prankster may serve as a school counselor’s

outlet for the structure and rules of the school environment.

Clinical mental health counselors, like counselor educators, scored higher

on the Creator and Sage archetype, but unlike counselor educators, they scored

higher on the Innocent archetype. These results indicate that clinical mental

health counselors may rely more heavily on valuing enlightenment (Sage) and

faith (Innocent) in their counseling, without including the Magician aspects

of research and understanding.

In terms of life satisfaction and meaning in life, it would be expected that

those who find meaning would also find satisfaction in their lives. The contrary,

that those who are still searching for meaning would be less likely to experience

satisfaction, was also shown to be true for this sample. In post hoc analysis, one

archetype, the Outlaw, was found to have a significant negative correlation with

both life satisfaction and the MLQ-Presence subscale but had a significant posi-

tive relationship with the MLQ-Search subscale. It would appear that counseling

professionals are uncomfortable seeing themselves as rule breakers or misfits. Also

interesting were the significant differences between groups regarding identifica-

tion with the Wounded Healer descriptor. It appears that counselor educators

and school counselors are less likely to have experienced, or acknowledge having

experienced, past significant personal challenges. This suggests that clinical mental

health counselors may have different needs that are being fulfilled by a career in

the counseling profession than counselor educators and school counselors.

The correlations between archetypes and life satisfaction show some signifi-

cant relationships of interest. For clinical mental health counselors, there was a

significant positive correlation with the Innocent archetype and life satisfaction,

indicating that clinical mental health counselors may rely more on faith and a

search for simplicity to strive for happiness. They may also use this approach in

applying counseling theory and techniques with clients. For school counselors,

life satisfaction was positively correlated with the Hero archetype. The Hero is

courageous and a crusader. Therefore, school counselor may possess higher life

satisfaction in their role as a protector and encourager of the nation’s youth. The

counselor educator group showed a positive correlation between life satisfaction

and the Caregiver archetype. More satisfaction may be realized by counselor

educations when they have the opportunity to express caring, compassion, and

benevolence as they mentor and guide future practitioners.

In summary, the results of this study provide insights into the unconscious

motivations and attitudes toward helping in the counseling profession. The

career choice and development literature (Holland, 1997; Parsons, 1909; Super,

1990) accentuates the need for individuals to gain self-understanding for ap-

propriate career matching and development. These results provide another way

of helping counselor educators and counselors develop greater personal acumen.

ACAASPAN_v14_n1_0415TEXT.indd 58 2/9/2015 8:47:29 AM

10

https://mds.marshall.edu/adsp/vol14/iss1/5

DOI: -

ADULTSPAN Journal April 2015 Vol. 14 No. 1 59

Implications

These findings hold specific implications for the counseling profession and

counselor education. Counselor educators who are supervising counselors may

find utility in using the archetype indicators as a descriptive tool to help students

gain personal insights. Understanding and pointing out the differences that may

exist in archetypes across the professions may help students make appropriate

career choices and assist student interns with transference and attraction issues

in counseling sessions. Specifically, helping clinical mental health counselors-in-

training to understand aspects of their personal wounds may assist these students

to avoid inappropriate personal disclosure and other countertransference issues.

Counselor educators may benefit by reflecting on balancing practice with teaching

and supervision to maintain life satisfaction. Finally, as the Magician, counselor

educators may assist both school and clinical mental health counselors in under-

standing the importance of research in the practice of professional counseling.

Limitations and Future Research

A number of potential limitations may affect the internal and external validity

of our findings. Selection bias is a factor because participants self-selected to

complete the study, and these participants may be different in unknown ways

from other individuals who chose not to complete the study. Although the

participant group was geographically diverse, it was not demographically rep-

resentative of the overall population, nor was it known if the participants were

representative of all individuals in the counseling field. Additional limitations

may also exist in terms of unequal group sizes. Lastly, self-report measures create

concerns because they may be influenced by social desirability, responses bias,

and lack of triangulation with other forms of data collection.

As we look to potential areas for future research, the present findings suggest that

there are inherent differences between those individuals seeking careers as clinical

mental health counselors, school counselors, and counselor educators. Further research

to better understand the unique educational needs of each group is indicated because

of the unique characteristics of each population. Additional research on the role of

archetypes in career choice and the presence of a calling also warrant further exploration.

REFERENCES

Auxier, C. R., Hughes, F. R., & Kline, W. B. (2003). Identity development in counselors-in-training. Counselor

Education and Supervision, 43, 25–38. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2003.tb01827.x

Bennet, G. (1979). Patients and their doctors: The journey through medical care. London, England: Bailliere Tindall.

Bonebright, C. A., Clay, D. L., & Ankenmann, R. D. (2000). The relationship of workaholism with

work–life conflict, life satisfaction, and purpose in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 47, 469–477.

doi:10.1037/0022-0167.47.4.469

Borders, L. D., & Usher, C. H. (1992). Post-degree supervision: Existing and preferred practices. Journal of

Counseling & Development, 70, 594–599.

Bruss, K. V., & Kopala, M. (1993). Graduate school training in psychology: Its impact upon the de-

velopment of professional identity. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 30, 685–691.

doi:10.1037/0033-3204.30.4.685

ACAASPAN_v14_n1_0415TEXT.indd 59 2/9/2015 8:47:29 AM

11Published by Marshall Digital Scholar, 2015

60 ADULTSPAN Journal April 2015 Vol. 14 No. 1

Campbell, J. (1949). The hero with a thousand faces. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

doi:10.2307/537371

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction With Life Scale. Journal of

Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75. doi:10.1037/t01069-000

Duffy, R. D., & Sedlacek, W. E. (2010). The salience of a career calling among college students: Exploring

group differences and links to religiousness, life meaning, and life satisfaction. The Career Development

Quarterly, 59, 27–41. doi:10.1002/j.2161-0045.2010.tb00128.x

Faber, M. A., & Mayer, J. D. (2009). Resonance to archetypes in media: There’s some accounting for taste.

Journal of Research in Personality, 43, 307–322. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2008.11.003

Fjelland, J. E., Barron, C. R., & Foxall, M. (2008). A review of instruments measuring two aspects of

meaning: Search for meaning and meaning in illness. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62, 394–406.

doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04597.x

Gibson, D. M., Dollarhide, C. T., & Moss, J. M. (2010). Professional identity development: A grounded

theory of transformational tasks of new counselors. Counselor Education and Supervision, 50, 21–37.

doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2010.tb00106.x

Hall, S. F., Burkholder, D., & Sterner, W. R. (2013). Examining spirituality and sense of calling in counseling

students. Counseling and Values, 59, 3–16. doi:10.1002/j.2161-007x.2014.00038.x

Hartwig Moorhead, H. J., Gill, C., Barrio Minton, C. A., & Myers, J. E. (2012). Forgive and forget?

Forgiveness, personality, and wellness among counselors-in-training. Counseling and Values, 57, 81–95.

doi:10.1002/j.2161-007x.2012.00010.x

Holland, J. L. (1997). Making vocational choices: A theory of vocational personalities and work environments

(3rd ed.). Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Jung, C. G. (1959). The concept of the collective unconscious. In Collected works (Vol. 9, Pt. 1, pp. 42–53).

London, England: Routledge. (Original work published 1936)

Jung, C. G. (1964). Approaching the unconscious. In C. Jung & M. L. Franz (Eds.), Man and his symbols

(pp. 18–104). London, England: Aldus.

Jung, C. G. (1967). The philosophical tree. In Collected works (Vol. 13, pp. 253–349). Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press.

Jung, C. G. (1968). The archetypes and the collective unconscious (R. Hull, Trans.) (2nd ed.). Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press.

Kern, E. O. (2014). The pathologized counselor: Effectively integrating vulnerability and professional identity.

Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 9, 304–316. doi:10.1080/15401383.2013.854189

McPeek, R. W. (2008). The Pearson-Marr Archetype Indicator and psychological type. Journal of Psychologi-

cal Type, 7, 52–67.

Meekums, B. (2008). Embodied narratives in becoming a counselling trainer: An autoethnographic study.

British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 36, 287–301. doi:10.1080/03069880802088952

Moodley, R. (2010). In the therapist’s chair is Clemmont E. Vontress: A wounded healer in cross-cultural

counseling. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 38, 2–15. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1912.2010.

tb00109.x

Moss, J. M., Gibson, D. M., & Dollarhide, C. T. (2014). Professional identity development: A grounded

theory of transformational tasks of counselors. Journal of Counseling & Development, 92, 3–12.

doi:0.1002/j.1556-6676.2014.00124.x

Parsons, F. (1909). Choosing a vocation. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. doi:10.1007/BF02106301

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (1993). Review of the Satisfaction With Life Scale. Psychological Assessment, 5,

164–172. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.5.2.164

Pearson, C. S., & Marr, H. K. (2002). Introduction to archetypes: A companion for understanding and using

the Pearson-Marr Archetype Indicator. Gainesville, FL: Center for Applications of Psychological Type.

Rogers, C. R. (1957). The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change. Journal of

Consulting Psychology, 21, 95–103. doi:10.1037/h0045357

Skovholt, T. M., & Ronnestad, M. H. (1992). Themes in therapist and counselor development. Journal of

Counseling & Development, 70, 505–515. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.1992.tb01646.x

Steger, M. F., & Dik, B. J. (2009). If one is looking for meaning in life, does it help to find meaning in

work? Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 1, 303–320. doi:10.1111/j.1758-0854.2009.01018.x

Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S., & Kaler, M. (2006). The Meaning in Life Questionnaire: Assessing the

presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53, 80–93. doi:10.1037/0022-

0167.53.1.80

ACAASPAN_v14_n1_0415TEXT.indd 60 2/9/2015 8:47:29 AM

12

https://mds.marshall.edu/adsp/vol14/iss1/5

DOI: -

ADULTSPAN Journal April 2015 Vol. 14 No. 1 61

Stoltz, K. B., Barclay, S., Reysen, R., & Degges-White, S. (2013). The use of occupational images in counselor

supervision. Counselor Education and Supervision, 52, 2–14. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6978.2013.00024.x

Stone, D. (2008). Wounded healing: Exploring the circle of compassion in the helping relationship. The

Humanistic Psychologist, 36, 45–51. doi:10.1080/08873260701415587

Super, D. E. (1990). A life-span, life-space approach to career development. In D. Brown & L. Brooks

(Eds.), Career choice and development: Applying contemporary theories to practice (2nd ed., pp. 197–261).

San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. doi:10.1016/0001-8791(80)90056-1

Temane, L., Khumalo, I. P., & Wissing, M. P. (2014). Validation of the Meaning in Life Questionnaire

in a South African context. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 24, 81–95. doi:10.4102/sajip.v39i1.1157

Trusty, J., Ng, K., & Watts, R. E. (2005). Model of effects of adult attachment on emotional empathy of

counseling students. Journal of Counseling & Development, 83, 66–77. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2005.

tb00581.x

Wegscheider, S. (1981). Another chance: Hope and health for the alcoholic family. Palo Alto, CA: Science &

Behavior Books.

ACAASPAN_v14_n1_0415TEXT.indd 61 2/9/2015 8:47:29 AM

13Published by Marshall Digital Scholar, 2015