For More Information

Visit RAND at www.rand.org

Explore the RAND Corporation

View document details

Support RAND

Purchase this document

Browse Reports & Bookstore

Make a charitable contribution

Limited Electronic Distribution Rights

is document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing

later in this work. is electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-

commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is

prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from

RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For

information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions.

Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16

e RAND Corporation is a nonprot institution that helps improve policy and

decisionmaking through research and analysis.

is electronic document was made available from www.rand.org as a public service

of the RAND Corporation.

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES

EDUCATION AND THE ARTS

ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT

HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE

INFRASTRUCTURE AND

TRANSPORTATION

INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS

LAW AND BUSINESS

NATIONAL SECURITY

POPULATION AND AGING

PUBLIC SAFETY

SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY

TERRORISM AND

HOMELAND SECURITY

is report is part of the RAND Corporation research report series. RAND reports

present research ndings and objective analysis that address the challenges facing the

public and private sectors. All RAND reports undergo rigorous peer review to ensure

high standards for research quality and objectivity.

C O R P O R AT I O N

Evaluating the Effectiveness

of Correctional Education

A Meta-Analysis of Programs That Provide

Education to Incarcerated Adults

Lois M. Davis, Robert Bozick, Jennifer L. Steele, Jessica Saunders,

Jeremy N. V. Miles

Sponsored by the Bureau of Justice Assistance

Bureau of Justice Assistance

U.S. Department of Justice

Evaluating the Effectiveness

of Correctional Education

A Meta-Analysis of Programs That Provide

Education to Incarcerated Adults

Lois M. Davis, Robert Bozick, Jennifer L. Steele, Jessica Saunders,

Jeremy N. V. Miles

Sponsored by the Bureau of Justice Assistance

C O R P O R A T I O N

The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy

and decisionmaking through research and analysis. RAND’s publications do

not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors.

Support RAND

—

make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at

www.rand.org/giving/contribute.html

R

®

is a registered trademark.

Cover photo courtesy of PrisonEducation.com.

© Copyright 2013 RAND Corporation

This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of

RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting

of RAND documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND documents are protected

under copyright law. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only,

as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or

reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on

reprint and linking permissions, please see the RAND permissions page (www.rand.org/pubs/

permissions.html).

RAND OFFICES

SANTA MONICA, CA • WASHINGTON, DC

PITTSBURGH, PA • NEW ORLEANS, LA • JACKSON, MS • BOSTON, MA

DOHA, QA • CAMBRIDGE, UK • BRUSSELS, BE

www.rand.org

The research described in this report was sponsored by the Bureau of Justice

Assistance and conducted in the Safety and Justice Program within RAND

Justice, Infrastructure, and Environment.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication.

ISBN: 978-0-8330-8108-7

This project was supported by Grant No. 2010-RQ-BX-001 awarded by the Bureau of Justice

Assistance to the RAND Corporation. The Bureau of Justice Assistance is a component of the

Office of Justice Programs, which also includes the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the National

Institute of Justice, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, the Office for

Victims of Crime, and the Office of Sex Offender Sentencing, Monitoring, Apprehending,

Registering, and Tracking. Points of view or opinions in this document are those of the authors

and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of

Justice.

iii

Foreword

Each year, thousands of incarcerated adults leave the nation’s prisons and jails and return to

their families and communities. While many successfully reintegrate into their communi-

ties, nd jobs, and become productive members of society, many others will commit new

crimes and end up being reincarcerated. Although a number of factors account for why some

ex-prisoners succeed and some don’t, we know that a lack of education and skills is one key

reason. is is why correctional education programs—whether academically or vocationally

focused—are a key service provided in correctional facilities across the nation. But do such

correctional education programs actually work? We care about the answer both because we

want ex-prisoners to successfully reenter communities and because we have a responsibility to

use taxpayer dollars judiciously to support programs that are backed by evidence of their

eectiveness—especially during dicult budgetary times like these. Across this Administra-

tion, we are committed to investing in evidence-based programming, investigating promising

practices, and making science a priority.

Fortunately, the passage of the Second Chance Act of 2007 gave us a chance to compre-

hensively examine the eectiveness of correctional education because it includes a specic pro-

vision to improve education in U.S. prisons and jails. e Bureau of Justice Assistance, with

guidance from the Oce of Vocational and Adult Education, competitively awarded a project

to the RAND Corporation in 2010. We asked RAND to comprehensively examine the cur-

rent state of correctional education for incarcerated adults and juveniles and where the eld is

headed, which correctional education programs are eective, and how eective programs can

be implemented across dierent settings. is valuable report—a new meta-analysis examin-

ing the eectiveness of correctional education programs—is a key part of that eort and can

help us answer the question of whether the nation’s investment in correctional education is

indeed achieving its intended outcomes.

e results presented here are truly encouraging. Conrming the results of previous meta-

analyses—while using more (and more recent) studies and an even more rigorous approach to

selecting and evaluating them than in the past—RAND researchers show that correctional

education reduces postrelease recidivism and does so cost-eectively. And the study also looks

at another outcome key to successful reentry—postrelease employment—and nds that cor-

rectional education may increase such employment. e reason the ndings for employment

are merely suggestive is that only one of the 19 studies that evaluated post-employment out-

comes used a highly rigorous methodology.

is need for more high-quality studies that would reinforce the ndings is one of the key

areas the study recommends for continuing attention. Just as important is the need to better

iv Evaluating the Effectiveness of Correctional Education

understand what makes some programs more eective than others—is it the program design,

the type of instruction, the length of the program, or, more likely, some combination of these

and other factors? Having such knowledge is key to telling us which programs should be devel-

oped and funded—which programs will provide the greatest return on taxpayer dollars. Other

parts of the RAND project, including an assessment of best practices derived from examining

current programs, will further illuminate what works, but new and ongoing studies should be

designed in ways that help isolate the causal eects of particular program designs.

e results provided here give us condence that correctional education programs are a

sound investment in helping released prisoners get back on their feet—and stay on their feet—

when they return to communities nationwide. We are pleased to have been able to work coop-

eratively across our two agencies with the RAND sta and to oer this important information.

Denise E. O’Donnell, J.D. Brenda Dann-Messier, Ed.D.

Director, Bureau of Justice Assistance Assistant Secretary

Oce of Justice Programs Vocational and Adult Education

U.S. Department of Justice U.S. Department of Education

v

Preface

e Second Chance Act of 2007 (Public Law 110-199) represented a historic piece of legisla-

tion designed to improve outcomes for and provide a comprehensive response to the increasing

number of individuals who are released from prisons, jails, and juvenile residential facilities and

returning to communities upon release. e Second Chance Act’s grant programs are funded

and administered by the Oce of Justice Programs within the U.S. Department of Justice. In

2010, for the rst time, funding was set aside for a comprehensive study of correctional educa-

tion. e Oce of Justice Programs’ Bureau of Justice Assistance awarded the RAND Corpo-

ration a cooperative agreement to undertake a comprehensive examination of the current state

of correctional education for incarcerated adults and juveniles and where it is headed, which

correctional education programs are eective, and how eective programs can be implemented

across dierent settings. One key task was to undertake a comprehensive review of the scien-

tic literature and a meta-analysis to synthesize the ndings from multiple studies as to the

eectiveness of correctional education programs in helping to reduce recidivism and improve

postrelease employment outcomes. In this report, we detail the meta-analytic approach and

ndings for academic programs and vocational training programs provided to incarcerated

adults. In a subsequent report, we will present the ndings for the overall project.

ese results will be of interest to federal and state policymakers; administrators of state

departments of corrections, public safety, and education; correctional as well as community

college educators; career technical training providers; and other organizations that provide

educational services and training to currently incarcerated or formerly incarcerated adults.

ese results will also be of interest to those in the U.S. Departments of Justice and Education

who are committed to ensuring the availability and quality of correctional education programs

for incarcerated adults.

The RAND Safety and Justice Program

e research reported here was conducted in the RAND Safety and Justice Program, which

addresses all aspects of public safety and the criminal justice system, including violence, polic-

ing, corrections, courts and criminal law, substance abuse, occupational safety, and public

integrity. Program research is supported by government agencies, foundations, and the private

sector.

is program is part of RAND Justice, Infrastructure, and Environment, a division of

the RAND Corporation dedicated to improving policy and decisionmaking in a wide range of

vi Evaluating the Effectiveness of Correctional Education

policy domains, including civil and criminal justice, infrastructure protection and homeland

security, transportation and energy policy, and environmental and natural resource policy.

Questions or comments about this report should be sent to the project leaders, Lois M.

Davis, Ph.D. (Lois_Davis@rand.org) and Robert Bozick, Ph.D. (Robert_Bozick@rand.org).

For more information about the Safety and Justice Program, see http://www.rand.org/safety-

justice or contact the director at sj@rand.org.

vii

Contents

Foreword ........................................................................................................ iii

Preface

............................................................................................................ v

Figures

........................................................................................................... xi

Tables

...........................................................................................................xiii

Summary

........................................................................................................xv

Acknowledgments

............................................................................................ xxi

Abbreviations

................................................................................................ xxiii

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction ..................................................................................................... 1

Background

....................................................................................................... 2

Barriers to Reentry for Incarcerated Prisoners and the Potential of Correctional Education

Programs to Address em

.............................................................................. 2

Overview of U.S. Correctional Education

.................................................................. 4

Previous Meta-Analyses of Correctional Education

......................................................... 5

Lipton, Martinson, and Wilks (1975)

...................................................................... 5

Wilson, Gallagher, and MacKenzie (2000)

................................................................ 6

MacKenzie (2006)

............................................................................................ 7

Aos, Miller, and Drake (2006)

.............................................................................. 8

Study’s Objective and Scope

.................................................................................... 8

Study’s Limitations

.............................................................................................. 10

Organization of is Report

................................................................................... 11

CHAPTER TWO

Study Methodology ...........................................................................................13

Introduction

.....................................................................................................13

Comprehensive Literature Search

.............................................................................14

Document Identication

.....................................................................................14

Eligibility Assessment

........................................................................................15

Scientic Review

................................................................................................17

Independent Reviews by the Scientic Review Team

....................................................17

Dening Treatment and Comparison Groups

............................................................18

Rating the Quality of the Research Design

...............................................................18

Operational Use of the Maryland SMS and WWC Rating Scheme

.................................. 20

viii Evaluating the Effectiveness of Correctional Education

Description of the Data ....................................................................................... 24

Analytic Approach

............................................................................................. 24

CHAPTER THREE

e Relationship Between Correctional Education and Recidivism ................................ 27

Introduction

.................................................................................................... 27

Measuring Recidivism

......................................................................................... 27

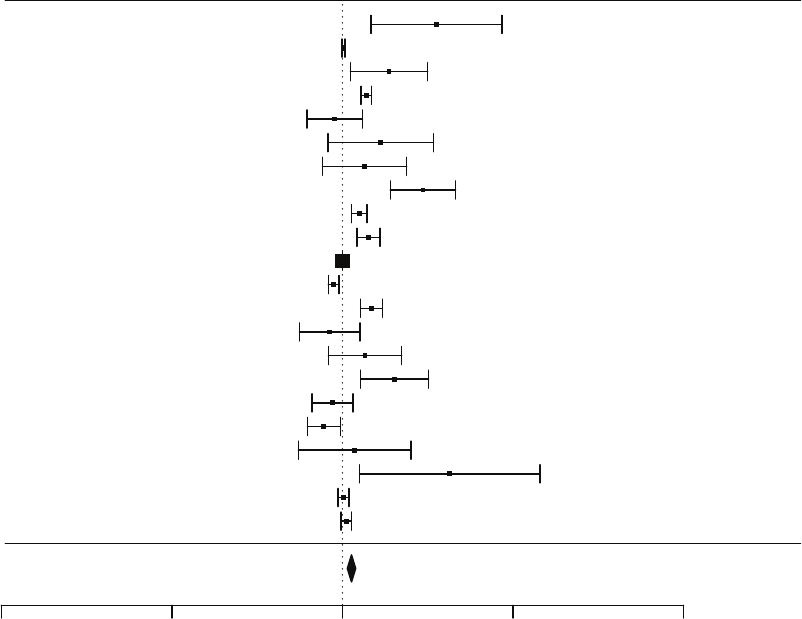

Results: Estimates of the Relationship Between Correctional Education and Recidivism

.............29

e Overall Relationship Between Correctional Education and Recidivism

..........................29

e Relationship Between Correctional Education and Recidivism in Studies with

High-Quality Research Designs

.......................................................................29

Interpreting the Relationship Between Correctional Education and Recidivism

.....................32

Role of Program Type and Instructional Delivery Method

..............................................33

Progra m Ty pe

................................................................................................ 34

Instructional Delivery Method

.............................................................................. 35

Comparison of the Costs of Correctional Education and Reincarceration Costs

...................... 36

Summary

.........................................................................................................39

CHAPTER FOUR

e Relationship Between Correctional Education and Employment ..............................41

Introduction

.....................................................................................................41

Measuring Employment

........................................................................................41

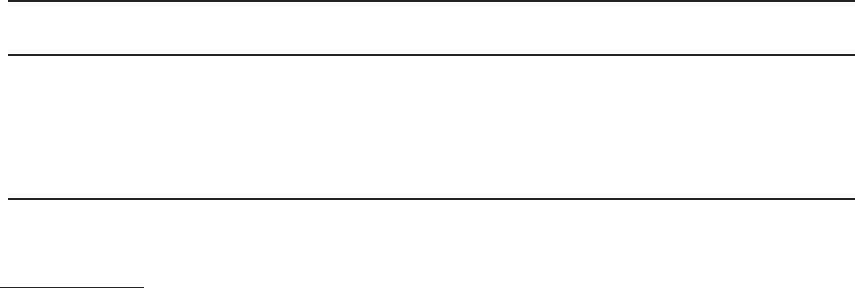

Results: Estimates of the Relationship Between Correctional Education and Employment

.......... 42

Interpreting the Relationship Between Correctional Education and Employment

.................. 44

Role of Program Type and Method Used to Collect Employment Data

............................... 45

Progra m Ty pe

.................................................................................................45

Method Used to Collect Employment Data

.............................................................. 46

Summary

.........................................................................................................47

CHAPTER FIVE

e Relationship Between Computer-Assisted Instruction and Academic Performance ........49

Introduction

.....................................................................................................49

Description of the Computer-Assisted Instructional Interventions

.......................................49

Measuring Academic Performance

........................................................................... 50

Creating a Common Performance Scale

.....................................................................51

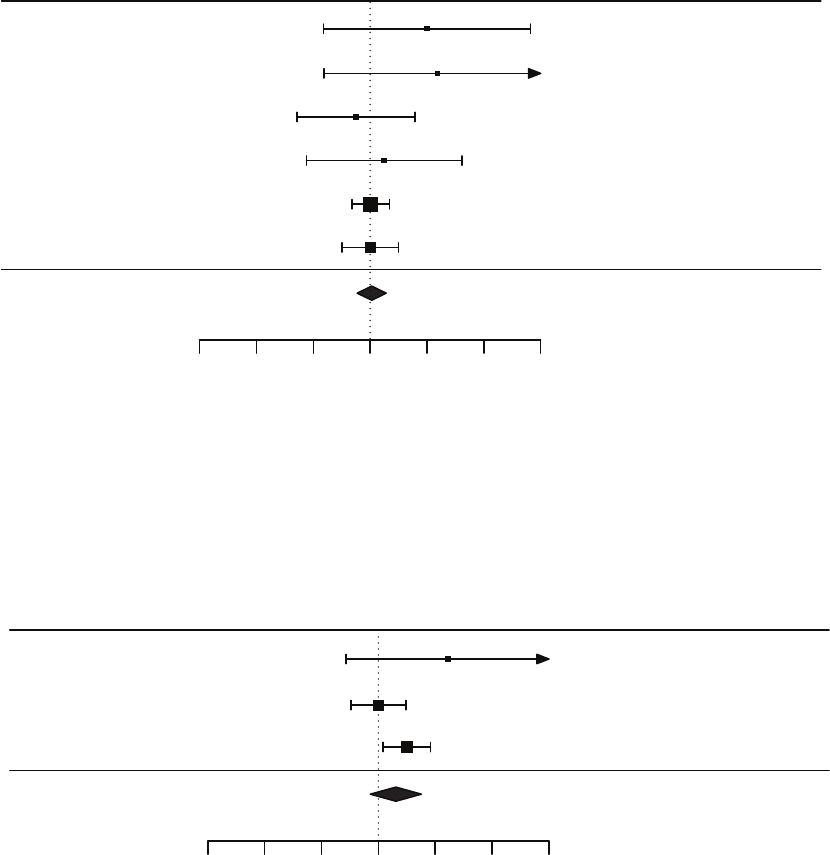

Results: Eects of Computer-Assisted Correctional Education on Student Performance in

Math and Reading

.........................................................................................52

Role of Program Type

......................................................................................... 54

Summary

........................................................................................................ 56

CHAPTER SIX

Conclusions .....................................................................................................57

Overall Summary of Findings

.................................................................................57

e Need to Improve the Research Evidence Base for Correctional Education

........................ 60

Applying Stronger Research Designs

......................................................................61

Measuring Program Dosage

.................................................................................63

Contents ix

Identifying Program Characteristics ....................................................................... 64

Examining More-Proximal Indicators of Program Ecacy

............................................ 64

Policy Implications

..............................................................................................65

APPENDIXES

A. Document Identication Parameters and Sources .................................................67

B. Scientic Review Team Members ......................................................................71

C. Meta-Analysis Diagnostic Tests ........................................................................73

Appendixes D–H are available online at

http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR266.html

References

.......................................................................................................81

xi

Figures

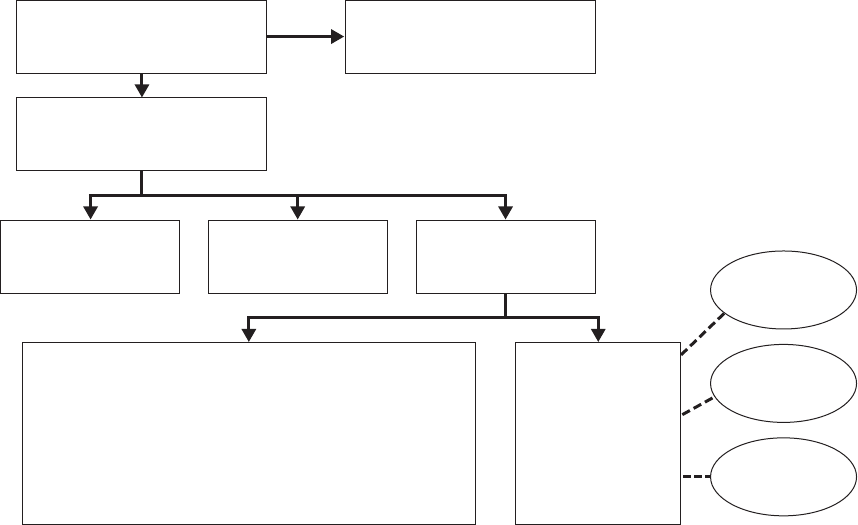

2.1. Eligibility Assessment of Potential Documents for Inclusion in the Meta-Analysis .......14

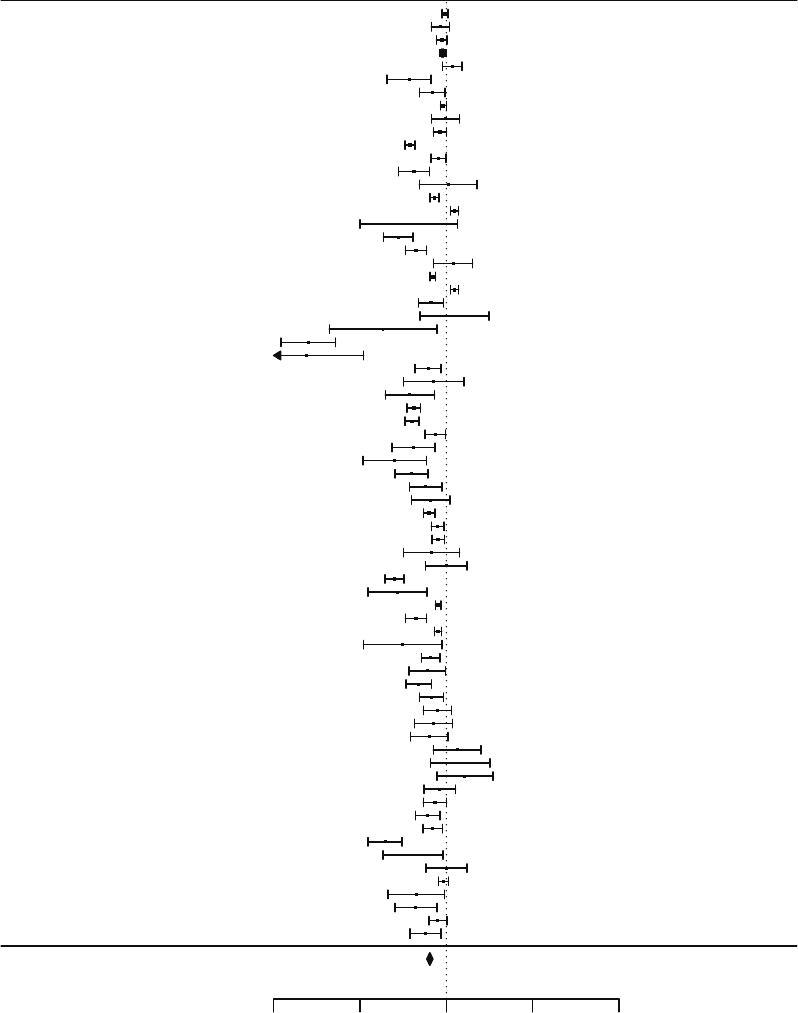

3.1. Odds Ratios for Each of the 71 Eect Size Estimates ........................................ 30

4.1. Odds Ratios for Each of the 22 Eect Size Estimates ........................................ 43

5.1. Reading Eect Estimates .........................................................................53

5.2. Mathematics Eect Estimates ....................................................................53

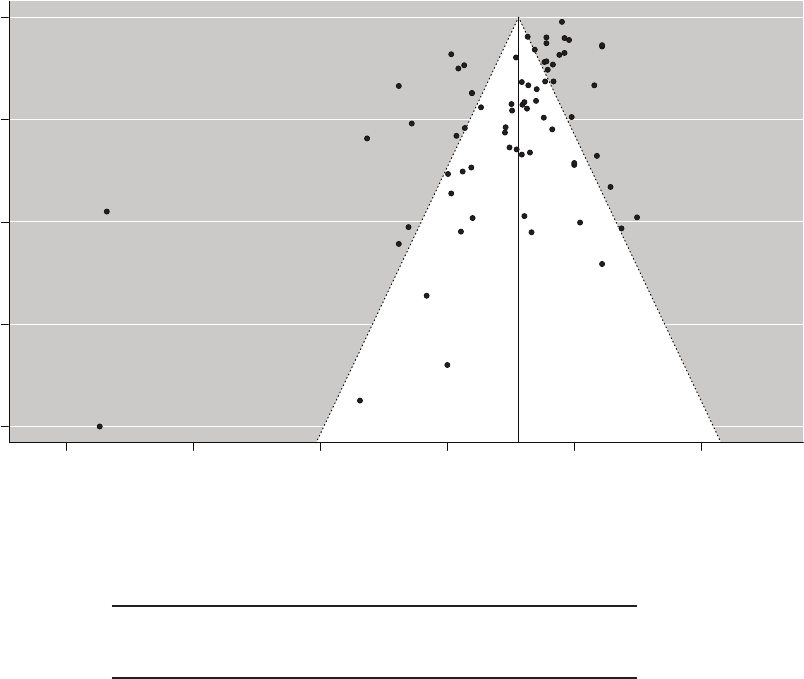

C.1. Funnel Plot for Studies of Recidivism ...........................................................74

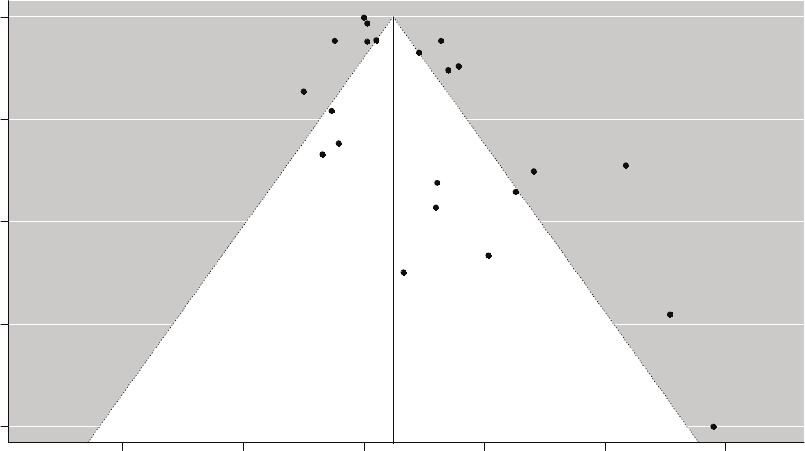

C.2. Funnel Plot for Studies of Employment ........................................................ 77

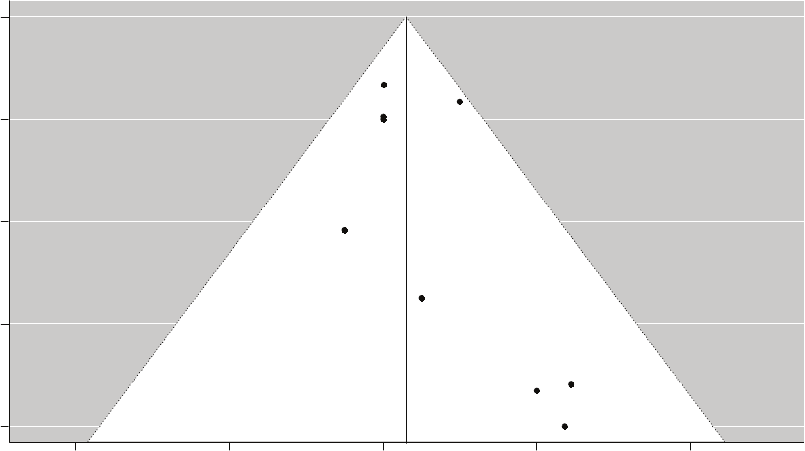

C.3. Funnel Plot for Studies of Computer-Assisted Instruction ...................................79

xiii

Tables

2.1. Operational Denitions of Evidence Rating Categories in the What Works

Clearinghouse Rating Scheme and the Maryland Scientic Methods Scale

............. 22

2.2. Distribution of Studies and Eect Sizes, by Rating Categories in the What Works

Clearinghouse Rating Scheme and the Maryland Scientic Methods Scale ...............25

3.1. Estimates of the Eect of Correctional Education Participation on the Odds of

Recidivating, by Levels of the Maryland Scientic Methods Scale ..........................31

3.2. Risk Dierence and Number Needed to Treat Based on Dierent Recidivism

Base Rates

...........................................................................................33

3.3. Estimates of the Eect of Correctional Education Participation on the Odds of

Recidivating, by Program Type ................................................................. 34

3.4. Estimates of the Eect of Correctional Education Participation on the Odds of

Recidivating, by Instructional Delivery Method ............................................. 36

3.5. Inputs into the Cost Analysis .....................................................................37

3.6. Cost Analysis Results ............................................................................. 38

4.1. Estimates of the Eect of Correctional Education Participation on the Odds of

Postrelease Employment, by Levels of the Maryland Scientic Methods Scale .......... 44

4.2. Estimates of the Eect of Correctional Education Participation on the Odds of

Obtaining Employment, by Program Type

.................................................... 46

4.3. Estimates of the Eect of Correctional Education Participation on the Odds of

Obtaining Employment, by Method Used to Collect Employment Data

................. 46

5.1. Estimates of the Eect of Computer-Assisted Instruction on Student’s Achievement

Grade Level, by Content Area and Program Type .............................................55

C.1. Leave-One-Out Analysis for Studies of Recidivism ...........................................74

C.2. Leave-One-Out Analysis for Studies of Employment .........................................78

C.3. Leave-One-Out Analysis for Studies of Computer-Assisted Instruction ................... 80

xv

Summary

Introduction

It is challenging to prepare oenders with the needed vocational skills and education to be

successful in reintegrating back into society. Oenders, on average, are less educated than the

general population. For example, in 2004, approximately 36 percent of individuals in state

prisons had attained less than a high school education compared with 19 percent of the general

U.S. population age 16 and over. In addition to having lower levels of educational attainment,

oenders often lack vocational skills and a steady history of employment, which is a signicant

challenge for individuals returning from prison to local communities. And the dynamics of

prison entry and reentry make it hard for this population to accumulate meaningful, sustained

employment experience. Finally, the stigma of having a felony conviction on one’s record is a

key barrier to postrelease employment.

On April 9, 2008, the Second Chance Act (Public Law 110-199) (SCA) was signed into

law. is important piece of legislation was designed to improve outcomes for individuals who

are incarcerated, most of whom will ultimately return to communities upon release. e SCA’s

grant programs are funded and administered by the Oce of Justice Programs (OJP) within

the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ). In 2010, funding was set aside, for the rst time under

the SCA, to conduct a comprehensive study of correctional education. OJP’s Bureau of Justice

Assistance (BJA) awarded the RAND Corporation a cooperative agreement to comprehen-

sively examine the current state of correctional education for incarcerated adults and juveniles

and where it is headed, which correctional education programs are eective, and how eective

programs can be implemented across dierent settings. One central task in that eort was to

comprehensively review the scientic literature and conduct a meta-analysis to synthesize the

ndings from multiple studies about the eectiveness of correctional education programs in

helping to reduce recidivism and improve employment outcomes for incarcerated adults within

U.S. state prisons.

In this report, we present the ndings from our meta-analysis, which will inform policy-

makers, educators, and correctional education administrators interested in understanding the

association between correctional education and reductions in recidivism and improvements in

employment and other outcomes.

To prepare for the meta-analysis, we rst conducted a comprehensive literature search

for published and unpublished studies released between 1980 and 2011 that examined the

relationship between correctional education participation and inmate outcomes. We focused

exclusively on studies published in English of correctional education programs in the United

States that included an academic and/or vocational curriculum with a structured instructional

component. A scientic review panel abstracted data, and the quality of the research design

xvi Evaluating the Effectiveness of Correctional Education

was rated using the Maryland Scientic Methods Scale and the U.S. Department of Educa-

tion’s What Works Clearinghouse rating scheme. Studies that met our eligibility criteria in

terms of intervention type, research design, and outcomes and that rated a 2 or higher on the

Maryland Scientic Methods Scale were included in the meta-analysis.

We used meta-analytic techniques to synthesize the eects of correctional education pro-

grams administered to adults across multiple studies. As with previous meta-analyses in this

area, our focus was largely on recidivism, because it is the outcome most often used in the lit-

erature. However, we also examined whether participating in a correctional education program

was associated with an increase in labor force participation and whether participating in a cor-

rectional education program with a computer-assisted instructional component was associated

with gains in achievement test scores. In addition, we conducted a cost analysis comparing the

direct costs of correctional education with those of re-incarceration to place our recidivism

ndings into a broader context.

Results

Relationship Between Correctional Education Programs and Recidivism

Our meta-analytic ndings provide additional support for the premise that receiving correc-

tional education while incarcerated reduces an individual’s risk of recidivating after release.

After examining the higher-quality research studies, we found that, on average, inmates who

participated in correctional education programs had 43 percent lower odds of recidivating than

inmates who did not. ese results were consistent even when we included the lower-quality

studies in the analysis. is translates into a reduction in the risk of recidivating of 13 percent-

age points for those who participate in correctional education programs versus those who do

not. is reduction is somewhat greater than what had been previously reported by Wilson,

Gallagher, and MacKenzie (2000), which showed an average reduction in recidivism of about

11 percentage points. Using more recent studies and ones of higher quality, our ndings com-

plement the results published by Wilson, Gallagher, and MacKenzie (2000), Aos, Miller, and

Drake (2006), and MacKenzie (2006) and provides further support to the assertion that cor-

rectional education participants have lower rates of recidivism than nonparticipants.

Given the high percentage of state prison inmates who have not completed high school,

participation in high school/general education development (GED) programs was the most

common approach to educating inmates in the studies we examined. Focusing only on stud-

ies that examined this kind of program relative to no correctional education, we found that

inmates who participated in high school/GED programs had 30 percent lower odds of recidi-

vating than those who had not. In general, studies that included adult basic education (ABE),

high school/GED, postsecondary education, and/or vocational training programs showed a

reduction in recidivism. However, we could not disentangle the eects of these dierent types

of educational programs, because inmates could have participated in multiple programs, and

the amount of time that they spent in any given program was rarely reported.

Relationship Between Correctional Education Programs and Employment

When we look at the relationship between correctional education and postrelease employment,

our meta-analyses found—using the full set of studies—that the odds of obtaining employment

postrelease among inmates who participated in correctional education (either academic or vocational

Summary xvii

programs) was 13 percent higher than the odds for those who had not participated. However, only

one study fell into the higher-quality category.

us, if policymakers want to base decisions on

the higher-quality studies alone, then we are limited in our ability to detect a statistically signif-

icant dierence between program participants and nonparticipants in postrelease employment.

Still, our results suggest a positive association between correctional education and postrelease

employment. Our ndings align with those produced in the Wilson, Gallagher, and MacKenzie

(2000) meta-analysis, which also found improved odds of employment among correctional

education participants.

When examining the relationship between correctional education and postrelease

employment, one might expect vocational training programs to be more adept than academic

education programs at imparting labor market skills, awarding industry-recognized creden-

tials, or connecting individuals with prospective employers. And, indeed, when we looked

at the relationship between vocational training—versus academic correctional education

programs—and postrelease employment, we found that individuals who participated in voca-

tional training programs had odds of obtaining postrelease employment that were 28 percent higher

than individuals who had not participated. In comparison, individuals who participated in aca-

demic programs (combining ABE, high school/GED, and postsecondary education programs)

had only 8 percent higher odds of obtaining postrelease employment than those individuals

who had not participated in academic programs. Although the results suggest that vocational

training programs have a greater eect than academic programs on one’s odds of obtaining

postrelease employment, there was no statistically signicant dierence between the odds

ratios for the two types of programs, because the number of vocational training studies was

relatively small.

Relationship Between Computer-Assisted Instruction and Academic Performance

We also examined the relationship between computer-assisted instruction and academic per-

formance. In this case, the outcomes of interest were standardized test scores in mathematics

or reading. We reviewed four studies that compared the achievement test scores of inmates

receiving computer-assisted instruction with the achievement test scores of inmates receiving

face-to-face instruction. In two of the studies, students in both the treatment and comparison

groups also received additional, traditional classroom instruction beyond the portion of their

instructional time that was computer-assisted. We estimated that the overall eect of computer-

assisted instruction relative to traditional instruction is 0.04 grade levels in reading, or about 0.36

months of learning, and 0.33 grade levels in mathematics, which represents about 3 months of

learning. In other words, on average across the studies, students exposed to computer-assisted

instruction relative to traditional instruction learned very slightly more in reading in the same

amount of instructional time and substantially more in mathematics. However, there was no

statistically signicant dierence in test scores between the dierent methods of instruction,

and given that the condence intervals included zero for both reading and mathematics, we

could not rule out the possibility that the eects estimated were due to chance alone. Because

computer-assisted instruction can be self-paced and supervised by a tutor or an instructor, it is

potentially less costly to administer. It is worth noting that, since the publication of these four

studies, the capability and utility of instructional technology has progressed substantially (U.S.

Department of Education, 2010), which suggests that the eects of the newer technologies may

potentially outstrip those found in the studies examined here.

xviii Evaluating the Effectiveness of Correctional Education

Comparison of the Costs of Correctional Education Programs and Reincarceration Costs

State policymakers, corrections ocials, and correctional education administrators are asking

a key question: How cost-eective is correctional education? Our cost analysis suggests that

correctional education programs are cost-eective. Focusing only on the direct costs of correc-

tional education programs and of incarceration itself, and using a three-year reincarceration

rate for a hypothetical pool of 100 inmates, we estimated that the three-year reincarceration

costs for those who did not receive correctional education would be between $2.94 million and

$3.25 million. In comparison, for those who did receive correctional education, the three-year

reincarceration costs would be between $2.07 million and $2.28 million. is means that rein-

carceration costs are $0.87 million to $0.97 million less for those who receive correctional edu-

cation. In comparison, our estimates indicate that the costs of providing education to inmates

would range from $140,000 to $174,400 for the pool of 100 inmates. is translates into a

per-inmate cost of correctional education ranging from $1,400 to $1,744, suggesting that pro-

viding correctional education is cost-eective compared with the cost of reincarceration. It is

worth noting that this estimate takes into account only the direct costs to the system, but it

does not consider such other costs as the nancial and emotional costs to victims of crime or to

the criminal justice system as a whole. Hence, it is a conservative estimate of the broader eect

that correctional education can potentially yield.

To further help interpret the cost savings, we also calculated the break-even point—

dened as the risk dierence in the reincarceration rate required for the cost of correctional

education to be equal to the cost of incarceration. For a correctional education program to be

cost-eective, we estimated that a program would need to reduce the three-year reincarcera-

tion rate by between 1.9 and 2.6 percentage points to break even. In fact, as noted, our meta-

analytic ndings show that participation in correctional education programs is associated with

a 13 percentage-point reduction in the risk of reincarceration three years after release from

prison.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Our meta-analytic ndings provide further support that receiving correctional education

while incarcerated reduces an individual’s risk of recidivating after release from prison. Our

ndings were stable even when we limited our analyses to those studies with more rigorous

research designs. We found a notable eect across all levels of education, from adult basic edu-

cation and GED programs to postsecondary and vocational education programs. Further, our

cost analysis suggests that correctional education programs can be cost-eective. As noted by

other researchers interested in estimating the eect of correctional education (e.g., MacKenzie,

2008; Gaes, 2008), we, too, found a number of methodological weaknesses in the current body

of research that substantially limit one’s ability to inform the direction of policy and the design

of eective programs. us, a number of questions of interest to educators and policymakers

remain that the current literature does not permit us to answer, such as understanding what

is inside the “black box” in terms of what program elements, for example, are associated with

eective programs.

In addition, much is changing in the eld of correctional education. e 2008 reces-

sion aected correctional education (and other rehabilitative) programs in a number of states

and led to some dramatic changes in the number of programs oered, the sizes of classes, the

Summary xix

modes of delivery, and the number of inmates who participate in these programs. A reduced

funding environment will likely be true for many correctional education programs for the near

future, and questions about the return on investment of these programs will likely continue to

be a topic in state-level budget discussions.

Going forward, there is a need to undertake studies that “drill down” to get inside the

black box and identify the characteristics of eective programs in terms of such variables as

curriculum, dosage, and quality. To inform policy and funding decisions at the state and fed-

eral levels, policymakers need additional information and a better understanding of how these

programs work (or do not work). In addition, we need to continue to build the evidence base in

this area. We provide recommendations for doing so in four critical areas: (1) applying stronger

research designs, (2) measuring program dosage, (3) identifying program characteristics, and

(4) examining more proximal indicators of program ecacy.

One option is for state and federal policymakers and foundations to invest in well-

designed evaluations of correctional education programs to inform such policy questions. Also,

researchers and program evaluators need to strive to implement rigorous research designs to

examine questions related to potential bias and program dosage and to measure both proximal

and distal outcomes. Funding grants and guidelines can help further the eld by requiring the

use of more rigorous research designs. Such funding would also enable correctional educators

to partner with researchers and evaluators to undertake rigorous and comprehensive evalu-

ations of their programs. Last, a study registry of correctional education evaluations would

help in further developing the evidence base in this eld to inform policy and programmatic

decisionmaking.

Findings from this study can be found on the project’s website: http://www.rand.org/jie/

projects/correctional-education.html.

xxi

Acknowledgments

We are particularly grateful for the guidance and feedback provided throughout this project by

our Bureau of Justice Assistance project ocers, Gary Dennis, Senior Policy Advisor for Cor-

rections, and urston Bryant, Policy Advisor. We are also grateful for the valuable input and

feedback provided by Brenda Dann-Messier, Assistant Secretary for Vocational and Adult Edu-

cation, and John Linton, Director, Oce of Correctional Education, Oce of Vocational and

Adult Education, U.S. Department of Education. We also appreciate the support and insights

provided by Stephen Steurer, Executive Director of the Correctional Education Association.

e overall direction of the project was guided in part by a steering committee that

included John Dowdell (Director of the Gill Center for Business and Economic Education

at Ashland University and Co-Editor of the Journal of Correctional Education), William

Sondervan (Professor and Director of Criminal Justice, Investigative Forensics, and Legal

Studies at the University of Maryland University College), Stephen Steurer (Executive Direc-

tor of the Correctional Education Association), and Susan Turner (Professor of Criminology,

Law, and Society, at the University of California–Irvine).

In addition, a number of individuals within and outside RAND contributed to vari-

ous aspects of the project. e Scientic Review Team members helped guide the selection of

intervention characteristics to be abstracted and served as independent reviewers in abstract-

ing the study information that were inputs for the meta-analysis. ey included Cathryn

Chappell (Ashland University), John Dowdell (Ashland University), Joseph Gagnon (Uni-

versity of Florida), Paul Hirscheld (Rutgers University), Michael Holosko (University of

Georgia), David Houchins (Georgia State University), Kristine Jolivette (Georgia State Univer-

sity), Larry Nackerud (University of Georgia), Ed Risler (University of Georgia), and Margaret

Shippen (Auburn University).

Without the help of the following people, our study would have not been possible. Sta

from the RAND library worked tirelessly to locate and procure all documents needed for our

study: Tomiko Envela, Brooke Hyatt, and Sachi Yagyu. A team of doctoral students in the

Pardee RAND Graduate School helped organize and review all the studies that were consid-

ered for inclusion into our meta-analyses: Nono Ayivi-Guedehoussou, Stephanie Chan, Megan

Cliord, Lopamudra Das, Russell Lundberg, Shannon Maloney, Christopher McLaren, and

Nicole Schmidt. Certain studies required additional review to ensure that the information

was coded properly. is was undertaken by Ph.D.-level research sta at RAND: Ramya

Chari, Sarah Greathouse, Lisa Sontag-Padilla, Vivian Towe, and Malcolm Williams. Susanne

Hempel and Becky Kilburn advised the project on systematic review procedures. Sue Phillips

provided website development support for the project, Aneesa Motala assisted with systematic

review software support, and Roald Euller provided programming support. We also wish to

xxii Evaluating the Effectiveness of Correctional Education

acknowledge the work of Paul Steinberg who served as the communications analyst on this

report. Dionne Barnes-Proby provided project management and research assistance, and Judy

Bearer provided administrative support. We also beneted from the editing and publications

production support provided by James Torr, Patricia Bedrosian, and Jocelyn Lofstrom.

Last, we appreciate the insights provided by our technical reviewers, Juan Saavedra, an

associate economist at RAND, and David Wilson, Chair of the Criminology, Law, and Society

Department at George Mason University.

xxiii

Abbreviations

ABE adult basic education

ABLE Adult Basic Learning Examination, Level II

AIMS Advanced Instructional Management System

ASE adult secondary education

AUTOSKILL AUTOSKILL Component Reading Subskills Program

BJA Bureau of Justice Assistance

BJS Bureau of Justice Statistics

CASAS Comprehensive Adult Student Assessment System

CTE career and technical education

DOJ Department of Justice

ESL English as a second language

GED General Education Development

Maryland SMS Maryland Scientic Methods Scale

NAAL National Assessment of Adult Literacy

OJP Oce of Justice Programs

PLATO PLATO instructional software package for mathematics, reading,

and language

PSE postsecondary education

RCT randomized controlled trial

RD regression discontinuity

SCA Second Chance Act of 2007 (Public Law 110-199)

SVORI Serious and Violent Oender Reentry Initiative

TABE Test of Adult Basic Education

TABE D Test of Adult Basic Education, Dicult Level

xxiv Evaluating the Effectiveness of Correctional Education

TABE M Test of Adult Basic Education, Medium Level

WWC U.S. Department of Education’s What Works Clearinghouse

1

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

On April 9, 2008, the Second Chance Act (Public Law 110-199) (SCA) was signed into law.

is important piece of legislation was designed to improve outcomes for individuals who are

incarcerated, most of whom will ultimately return to communities upon release. e Second

Chance Act’s grant programs are funded and administered by the Oce of Justice Programs

(OJP) within the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ). In 2010, for the rst time under the SCA,

funding was set aside for a comprehensive study of correctional education. OJP’s Bureau of

Justice Assistance (BJA) awarded the RAND Corporation a cooperative agreement to com-

prehensively examine the current state of correctional education for incarcerated adults and

juveniles and where it is headed, which correctional education programs are eective, and how

eective programs can be implemented across dierent settings. One key task in that eort was

to comprehensively review the scientic literature and conduct a meta-analysis to synthesize

the ndings from multiple studies about the eectiveness of correctional education programs

in helping to reduce recidivism and improve employment outcomes.

In this report, we examine the evidence about the eectiveness of correctional education

for incarcerated adults in the United States. By correctional education, we mean the following:

• adult basic education (ABE): basic skills instruction in arithmetic, reading, writing, and,

if needed, English as a second language (ESL)

• adult secondary education (ASE): instruction to complete high school or prepare for a cer-

ticate of high school equivalency, such as the General Education Development (GED)

• vocational education or career and technical education (CTE): training in general employ-

ment skills and in skills for specic jobs or industries

• postsecondary education (PSE): college-level instruction that enables an individual to

earn college credit that may be applied toward a two-year or four-year postsecondary

degree.

Although some may consider life skills programs a part of correctional education, our

project focuses specically on the four types of academic and vocational training programs

summarized above. We also limit our focus to correctional education programs provided in

the institutional setting, as opposed to postrelease or community-based programs. Finally, our

focus is on correctional education programs provided at the state level. ese foci enable us

to address the question of what is known about the eectiveness of correctional education—

specically, academic programs and vocational training programs—for incarcerated adults in

U.S. state prisons.

2 Evaluating the Effectiveness of Correctional Education

Our analyses will be of special interest to correctional education administrators, correc-

tions ocials, and state policymakers who are interested in understanding the role that cor-

rectional education plays in the rehabilitation of and facilitation of incarcerated individuals’

reentry back into society and who must carefully consider how they will allocate resources

in a scally constrained environment. Our ndings will inform them about whether there is

an association between correctional education and recidivism, postrelease employment, and

achievement test scores.

In the remainder of this chapter, we rst provide an overview of the eld of correctional

education. en, as context for our meta-analysis, we summarize previous meta-analyses that

have been done on correctional education. We then summarize the study’s objectives and

scope, discuss the study’s limitations, and describe a roadmap for the remaining chapters.

Background

e growth in the prison population for the past 40 years has been well-documented. In 2010,

there were 1.6 million state and federal prisoners in the United States, with more than 700,000

incarcerated individuals leaving federal and state prisons each year (Guerino, Harrison, and

Sabol, 2012). About half of state prison inmates in 2009 were serving time for violent oenses,

and 19 percent, 18 percent, and 9 percent of state prison inmates were serving time for prop-

erty, drug, and public-order oenses, respectively. An enduring problem facing the broader

system of criminal justice is the high rate of recidivism in the United States: Within three years

of release, four out of ten U.S. state prisoners will have committed new crimes or violated the

terms of their release and be reincarcerated (Pew Center on the States, 2011). Devising pro-

grams and strategies to reduce recidivism requires understanding the unique challenges that

individuals face upon release as well the current state of programs in place to mitigate such

challenges. We describe both in turn as they pertain to correctional educational programs.

Barriers to Reentry for Incarcerated Prisoners and the Potential of Correctional Education

Programs to Address Them

Visher and Lattimore’s (2007) evaluation of the Serious and Violent Oender Reentry Ini-

tiative (SVORI) found that education, job training, and employment were among the com-

monly cited needs of incarcerated prisoners reintegrating back into society. But it is challeng-

ing to prepare individuals with the needed vocational skills and education to be successful in

reintegrating. Ex-oenders, on average, are less educated than the general population

(MacKenzie, 2008; Tolbert, 2012). Analysis of data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics’

(BJS’s) Survey of Inmates in State Correctional Facilities and the National Assessment of Adult

Literacy (NAAL) showed that 36.6 percent of individuals in state prisons had attained less

than a high school education in 2004 compared with 19 percent of the general U.S. popula-

tion age 16 and over (Crayton and Neusteter, 2008). Because many inmates lack a high school

diploma, the GED certicate is an important way for them to complete basic secondary educa-

tion (Harlow, 2003). In 2004, 32 percent of state prisoners had earned a GED compared with

5 percent of the general population, whereas only 16.5 percent of state prisoners had a high

school diploma compared with 26 percent of the general population (Crayton and Neusteter,

2008). With respect to postsecondary education, 51 percent of the general U.S. adult popu-

Introduction 3

lation had at least some postsecondary education compared with only 14.4 percent of state

prison inmates.

Literacy levels for the prison population also tend to be lower than that of the general U.S.

population. e 2003 NAAL assessed the English literacy of a sample of 1,200 inmates (age 16

and over) in state and federal prisons and a sample of 18,000 adults (age 16 and over) living in

U.S. households. Individuals were measured on three dierent literacy scales: prose, document,

and quantitative.

1

On average, inmates had lower scores on all three scales than the general

U.S. population (Greenberg, Dunleavy, and Kutner 2007). A higher percentage of the prison

population had average scores that fell within the basic level

2

for all three measures of literacy

compared with the household population. For example, 40 percent of the prison population

was at the basic level for prose literacy compared with 29 percent of the household population;

39 percent of the prison population, for quantitative literacy compared with 33 percent of the

household population; and 35 percent of the prison population, for document literacy com-

pared with 22 percent of the household population. All these comparisons were statistically

signicant (Greenberg, Dunleavy, and Kutner, 2007).

In addition to lower levels of educational attainment, the lack of vocational skills and

of a steady history of employment (Petersilia, 2003; Western, Kling, and Weiman, 2001)

also represents a signicant challenge for individuals returning to local communities (Travis,

Solomon, and Waul, 2001). Incarceration aects employment and earnings in a number of

ways. Using data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study, an analysis of the

eects of incarceration on the earnings and employment in a sample of poor fathers found

that the employment rates of formerly incarcerated men were about 6 percentage points lower

than those for a similar group of men who had not been incarcerated (Gellar, Garnkel, and

Western, 2006). Additionally, incarceration was also associated with a 14–26 percent decline

in hourly wages. Given the high incarceration rates in the United States and the fact that many

oenders cycle in and out of prison, Raphael (2007–08) noted that the dynamics of prison

entry and reentry inhibited the accumulation of meaningful sustained employment experience

in this population.

Further, the stigma of having a felony conviction on one’s record is a key barrier to

postrelease employment (Pager, 2003). Holzer, Raphael, and Stoll (2003) conducted a series

of surveys of employers in four major U.S. cities and found that employers were much more

averse to hiring ex-oenders than in hiring any other disadvantaged group. Willingness to hire

ex-oenders was greater for jobs in construction or manufacturing than for those in the retail

trade and service sectors; employers’ reluctance was greatest for violent oenders than for non-

violent drug oenders.

Pager (2003) conducted an audit survey of approximately 200 employers in Milwau-

kee and generated four groups of male job applicants who were very similar in educational

and work experience credentials but diered by whether they were oenders or nonoenders

and by race. Pager found that black oenders received less than one-seventh the number of

oers received by white nonoenders with comparable skills and experience. Also, black non-

1

Prose literacy measures the knowledge and skills needed to search, comprehend, and use information from continuous

texts. Document literacy measures the knowledge and skills needed to search, comprehend, and use information from non-

continuous texts. Quantitative literacy measures the knowledge and skills needed to identify and perform computations

using numbers that are embedded in printed materials.

2

Literacy levels include Below Basic, Basic, Intermediate, and Procient.

4 Evaluating the Effectiveness of Correctional Education

oenders generated fewer than half as many oers as white nonoenders—14 percent versus

34 percent, respectively. In terms of dierences by racial group, 17 percent of white oenders

received a job oer compared with only 5 percent of black oenders. Another barrier is that, in

many states, employers can be held liable for the criminal actions of their employees (Raphael,

2007–08). Taken together, lower overall educational attainment, lower levels of literacy, and

diculty securing employment upon release underscores the importance of educational pro-

gramming for this population.

Overview of U.S. Correctional Education

Most state correctional institutions (84 percent) oer some type of correctional education

programming (Stephan, 2008, Appendix Table 18). Data from the BJS 2005 Census of State

and Federal Correctional Facilities indicate that 66 percent of state correctional facilities

oered literacy or 1st–4th grade education programs, 64 percent oered 5th–8th grade educa-

tion programs, 76 percent oered secondary or GED, 50 percent oered vocational training,

33 percent oered special education, and 33 percent oered college courses (Stephan, 2008).

Although most state prison facilities oer some form of education, participation rates

vary and, in fact, have declined somewhat over time. For example, between 1997 and 2004,

participation rates in ABE, GED, postsecondary, and vocational training programs all showed

a modest decline (Crayton and Neusteter, 2008). In 2004, 52 percent of state prison inmates

reported having participated in a correctional education program since admission to a correc-

tional facility (Harlow, 2003). Only 27 percent of state prison inmates reported having partici-

pated in vocational training programs; 19 percent reported having participated in secondary

education programs (i.e., high school/GED); 2 percent in adult basic education; and 7 percent

in adult postsecondary education programs (Crayton and Neusteter, 2008).

Reasons for the low participation rates may include lack of programs or lack of aware-

ness of program opportunities, reduced funding for correctional education programs because

of state budget constraints, or competing demands (e.g., when participation is discretionary,

an individual might elect to participate in an employment program rather than an education

program) (Crayton and Neusteter, 2008; Tolbert, 2012). In addition, states dier as to whether

participation in correctional education programs for incarcerated adults is mandatory or vol-

untary. A survey of state correctional education programs in 2002 conducted by McGlone

found that 22 of the 50 states had adopted legislation or implemented policy requiring man-

datory education for prisoners. Of those requiring mandatory participation, ten states had

achieving a GED as the requirement for program completion (McGlone, 2002).

e administration and delivery of correctional education also diers from state to state.

For example, dierent entities—state departments of corrections, education, public safety, or

labor—may be responsible for administering and nancing correctional education programs

for their prison systems. Some states have their own correctional school district, such as Texas,

Florida, and Ohio. Some states may contract with community colleges to provide GED prepa-

ration, postsecondary education, or vocational training programs; other states may contract

out only some of their programs. In addition, privately operated corrections rms also have

responsibility for providing correctional education to adult prisoners. In 2011, approximately

8 percent of the U.S. state prison population was housed in privately operated facilities (Glaze

and Parks, 2012).

Introduction 5

Previous Meta-Analyses of Correctional Education

Understanding the role that correctional education plays in rehabilitation and reentry back

into society is the key goal of our study and meta-analysis. As a backdrop to our study, we rst

synthesize ndings from previous meta-analyses of correctional education programs in the

United States. In keeping with our study goals, we discuss only meta-analyses that have an

explicit focus on education programs administered primarily to adult oenders in correctional

facilities. According to our review, there have been three major published meta-analyses that

meet these criteria: Wilson, Gallagher, and MacKenzie (2000); MacKenzie (2006); and Aos,

Miller, and Drake (2006).

3

ese studies dier in their parameters, methods, and conclusions.

We review the ndings from each of these meta-analyses in turn, focusing rst on a landmark

systematic review of correctional education programs conducted by Lipton, Martinson, and

Wilks (1975) that set the stage for the current policy discourse and research direction in the

eld.

4

Lipton, Martinson, and Wilks (1975)

In 1975, Douglas Lipton, Robert Martinson, and Judith Wilks published a systematic review

of 231 studies of prisoner rehabilitation programs spanning the years 1945 to 1967—a review

that provided the rst major stocktaking of the potential ecacy of correctional education.

Commissioned by the New York State Governor’s Special Committee on Criminal Oenders,

this seminal review was developed in response to the lack of evidence about whether the array

of programs and reform eorts in place at the time were successfully preparing prisoners for

reintegration into their communities. For studies to be included in their review, Lipton and his

colleagues required that studies use a treatment and comparison group design, with the treat-

ment group composed of program participants and the comparison group composed of non-

participants. To determine whether dierent types of programs were working, they tallied the

ndings from individual studies—those that favored the treatment group, those that favored

the comparison group, and those with no discernible dierence between the treatment and

comparison group—and drew conclusions based on the frequency of statistically signicant

relationships.

Within their sample of 231 programs, Lipton and his team identied a subset of “skill-

development programs,” which consisted of academic and/or vocational training. ey sum-

marized comparisons of program participants and nonparticipants in studies that used recidi-

vism and employment as outcomes. Across eight studies that assessed recidivism, three showed

signicantly lower rates of recidivism among program participants, and one showed signi-

cantly higher rates of recidivism among program participants. e other four studies showed

3

e studies included in these meta-analyses are largely based on studies of correctional education programs in the United

States. However, a handful of international studies are also included.

4

Since the publication of the landmark Lipton, Martinson, and Wilks study, there have been other systematic reviews of

adult correctional education that do not apply meta-analytic methods (e.g., Gaes, 2008), and there have been meta-analyses

of correctional education programs administered to juvenile oender populations (e.g., Lipsey, 2009). With the exception

of the Lipton, Martinson, and Wilks study, which is important to acknowledge because of its seminal role in the eld, we

discuss only meta-analyses of adult correctional education programs, because their methods, ndings, and conclusions are

most relevant for providing context to our study. Additionally, readers should note that we are aware of two dissertations

(Chappell, 2003; Wells, 2000) that have used meta-analytic techniques to assess the relationship between correctional edu-

cation and recidivism. We do not review their analyses in depth here, but their ndings, by and large, accord with those of

Wilson, Gallagher, and MacKenzie (2000); MacKenzie (2006); and Aos, Miller, and Drake (2006).

6 Evaluating the Effectiveness of Correctional Education

no dierences between the treatment and comparison groups. In two studies that examined

employment as an outcome, oenders who participated in vocational training programs fared

worse than nonparticipants after being released. Overall, their review found no conclusive evi-

dence that correctional education was benecial and found that, in some cases, it might even

be harmful.

Lipton’s systematic review is notable, in part, because it set the tone for future research

and policy discourse in the eld. In 1974, one year before the release of the study, Robert

Martinson, the study’s second author, published a preview of the ndings in a commentary

“What Works?—Questions and Answers About Prison Reform” in e Public Interest. In it,

Martinson wrote: “it can safely be said that they [the studies included in their review] provide

us with no clear evidence that education or skill development programs have been success-

ful” (p. 27). Martinson’s summation cast doubt on the utility of educational programming

within the broader system of corrections and generated the provocative conclusion that “noth-

ing works” in prisoner rehabilitation. Although the “nothing works” tagline was never used in

the full empirical report, the tagline from Martinson’s commentary became synonymous with

the Lipton, Martinson, and Wilks review; as a result, federal- and state-sponsored initiatives to

address the needs of prisoners were eectively put on the defensive and in some cases curtailed.

Wilson, Gallagher, and MacKenzie (2000)

e empirical documentation of the Lipton study, along with Martinson’s critique, galvanized

eorts to improve existing academic and vocational training programs and to develop new

methods of educating prisoners. However, it was not until 25 years later, in 2000, that the

ecacy of correctional education was revisited through a formal meta-analysis conducted by

David Wilson, Catherine Gallagher, and Doris MacKenzie (2000) at the University of Mary-

land. eir meta-analysis included 33 studies of correctional education programs administered

to adults published after 1975—a time period that broadly covered the time since the Lipton

study was released.

e Wilson, Gallagher, and MacKenzie study attempted to improve on two limitations

of Lipton’s work: (1) e Lipton study did not address the magnitude of dierences in out-

comes between treatment and comparison groups, and (2) the Lipton study did not explicitly

account for variation in the quality of the research designs across studies. With respect to the

former limitation, Lipton’s review simply summed up the number of studies that yielded sta-

tistically signicant dierences between the treatment and comparison groups and based the

study’s conclusions on the preponderance of eects in one direction or the other; this approach

is sometimes referred to as a “vote counting” approach, in which each study gets a vote in the

“signicant” or the “not signicant” column, and the votes are counted (Field, 2005). Unfor-

tunately, this approach essentially obscures the magnitude of the eects across studies. In other

words, a large dierence favoring the treatment group “counts the same” as a small dierence

favoring the comparison group.

With respect to the latter limitation, Lipton’s review discussed dierences in method-

ological quality, highlighting (where appropriate) studies with carefully or poorly selected com-

parison groups. However, this variation in research design did not factor into how they tallied

statistically signicant program eects.

To address these limitations, Wilson and his team used formal meta-analytic techniques,

which average ndings of multiple studies into a single parameter of program or “treatment

Introduction 7

group” ecacy.

5

Additionally, they rated each study using a scale that they and their colleagues

at the University of Maryland developed specically for systematic reviews of correctional pro-

grams (Sherman et al., 1997). is scale, referred to as the Maryland Scientic Methods Scale

(the Maryland SMS), classies studies as either experimental or quasi-experimental. Following

Shadish, Cook, and Campbell (2002), experimental studies are dened as those that randomly

assign participants to treatment and control-group status, whereas quasi-experimental studies

are those that employ both a treatment and comparison group, but in which group member-

ship is not randomly assigned.

Among the quasi-experimental studies, the Maryland SMS further classies them accord-

ing to the quality of statistical controls they employ. Studies from most to least rigorous are

classied as follows: Level 5 indicates a well-executed randomized controlled trial (or RCT);

Level 4 indicates a quasi-experimental design with very similar treatment and comparison

groups; Level 3 indicates a quasi-experimental design with somewhat dissimilar treatment

and comparison groups, but reasonable controls for dierences; Level 2 indicates a quasi-

experimental design with somewhat dissimilar treatment and comparison groups and with

limited and/or no controls for dierences; and Level 1 indicates a study with no separate com-

parison group. Wilson and colleagues included only studies that received at least a Level 2

rating and then used the scale as a control variable to determine whether their ndings were

dependent on the research designs used by the studies’ authors.

Whereas the Lipton study documented mostly mixed results, the Wilson study found

that correctional programs were benecial, by and large. In their meta-analysis, they demon-

strated that participation in academic programs—including ABE, GED, and postsecondary

education programs—was associated with an average reduction in recidivism of about 11 per-

centage points. is nding was robust when controlling for ratings on the Maryland SMS.

Academic program participation was also associated with a greater likelihood of employment,

although they did not quantify the relationship in terms of a percentage increase/decrease in

the same way they did for recidivism. Vocational training program participation did not yield a

consistent relationship with recidivism but was associated with increased odds of employment.

Wilson and his team’s ndings, based on more recent programs and more rigorous methods of

analysis, questioned the Martinson study’s claim that “nothing works.”

6

MacKenzie (2006)

A few years later in 2006, Doris MacKenzie, a co-author of the Wilson study, updated their

original meta-analysis. In this update, she included a handful of newer studies and limited

her sample to only those studies published after 1980. Additionally, she limited her sample of

studies to only those receiving a Level 3 or higher rating on the Maryland SMS, thereby elimi-

nating studies from the predecessor meta-analysis with Wilson and Gallagher that had the

weakest study designs. In her re-analysis, she again found that academic program participation

appeared benecial: e odds of not recidivating were 16 percent higher among academic pro-

gram participants than nonparticipants. However, with the new sample parameters in place,

she now found that vocational program participation was associated with a reduction in recidi-

5

Meta-analytic techniques were not yet developed at the time of the Lipton study.

6

Since the publication of the Lipton study, a number of criminologists and policymakers questioned the claim that “noth-

ing works.” However, it was not until the Wilson, Gallagher, and MacKenzie study’s meta-analysis that a comprehensive

evaluation of the literature was synthesized in a systematic way to directly challenge the conclusion of the Lipton study.

8 Evaluating the Effectiveness of Correctional Education

vism: e odds of recidivating were 24 percent lower among vocational program participants

than nonparticipants. She did not update the analysis of employment.

Aos, Miller, and Drake (2006)

Also in 2006, Steve Aos, Marna Miller, and Elizabeth Drake of the Washington State Institute

for Public Policy conducted a meta-analysis of 571 oender rehabilitation programs for adults

and for juveniles, ranging from counseling to boot camps to education. ey limited their

sample to studies conducted from 1970 onward and, like MacKenzie’s meta-analysis published

the same year, they included only studies that received at least a Level 3 rating on the Mary-

land SMS. In analyzing 17 studies of academic education programs and four studies of voca-

tional education programs administered to adults, they found results that largely agreed with

MacKenzie’s: On average, participants have lower rates of recidivism than their nonpartici-

pant peers. Specically, they found that academic program participation was associated with a

7 percent reduction in recidivism, and vocational program participation was associated with a

9 percent reduction in recidivism.

In sum, early reviews of correctional education programs administered to adults by Lipton,

Martinson, and Wilks (1975) found inconclusive evidence to support their ecacy. e lack

of consistent positive eects contributed to the popular belief that “nothing works” in pris-

oner rehabilitation; however, this conclusion may have been premature, given that appropriate

analysis techniques had not been developed. More recent reviews using meta-analysis tech-

niques question the conclusions of the earlier work, nding evidence of a relationship between

correctional education program participation before release and lower odds of recidivat-

ing after release. However, the most recent meta-analyses (Aos, Miller, and Drake, 2006;

MacKenzie, 2006) did not consider employment outcomes; thus, whether program participa-

tion is associated with postrelease success in the labor market remains unclear.

Study’s Objective and Scope

As with the meta-analyses described above, our study aims to understand whether the body

of relevant research to date supports the proposition that correctional education programs

can help successfully prepare oenders for community reintegration upon release. Following

the lead of Wilson and colleagues, MacKenzie, and Aos and colleagues, we use meta-analytic

techniques to synthesize the eects of correctional education programs administered to adults

across multiple studies. In doing so, our goal is to build on the contributions of their work,

while extending them in a number of key ways, which we describe below.

First, our study examines multiple outcomes: recidivism, employment, and achievement

test scores. As with previous syntheses, our focus is largely on recidivism, because it is the out-

come most often used in the literature, and the ability to avoid recidivism is arguably an impor-

tant marker of successful rehabilitation. However, we also examine whether participating in a

correctional education program is associated with an increase in labor force participation and

whether participating in a correctional education program with a computer-assisted instruc-

tional component is associated with gains in achievement test scores.

Acquiring steady employment postrelease has been shown to be an important factor in

preventing recidivism among ex-oenders (Laub and Sampson, 2003; Uggen, 2000), and

among the civilian population, improving the acquisition of academic skills and concepts is

Introduction 9

vital in securing employment (Klerman and Karoly, 1994). In terms of life-course or devel-

opmental criminology, an emergent body of research has shown that desistance from deviant