00_WAUGH_BTGOP_FM.indd 3 4/26/2017 10:54:19 AM

Learning Matters

An imprint of SAGE Publications Ltd

1 Oliver’s Yard

55 City Road

London EC1Y 1SP

SAGE Publications Inc.

2455 Teller Road

Thousand Oaks, California 91320

SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd

B 1/I 1 Mohan Cooperative Industrial Area

Mathura Road

New Delhi 110 044

SAGE Publications Asia-Pacic Pte Ltd

3 Church Street

#10-04 Samsung Hub

Singapore 049483

Editor: Amy Thornton

Production controller: Chris Marke

Project management: Deer Park Productions

Marketing manager: Dilhara Attygalle

Cover design: Wendy Scott

Typeset by: C&M Digitals (P) Ltd, Chennai, India

Printed in the UK

2017 Editorial matter Wendy Jolliffe and David

Waugh; Chapter 1 Yasmin Valli; Chapters 2 and 11

Wendy Jolliffe; Chapter 3 Wendy Delf; Chapter 4

Hilary Smith; Chapter 5 Julia Lawrence; Chapters 6

and 7 Paul Hopkins; Chapter 8 Claire Head; Chapter

9 Kamil Trzebiatowski; Chapter 10 John Bennett;

Chapter 12 Jonathan Doherty and David Waugh;

Chapter 13 Alison McManus

Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of

research or private study, or criticism or review, as

permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents

Act 1988, this publication may be reproduced, stored

or transmitted in any form, or by any means, only with

the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in

the case of reprographic reproduction, in accordance

with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright

Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction

outside those terms should be sent to the publishers.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017935030

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the

British Library

ISBN 978 1 4739 9912 1 (pbk)

ISBN 978 1 4739 9911 4

At SAGE we take sustainability seriously. Most of our products are printed in the UK using FSC papers and boards.

When we print overseas we ensure sustainable papers are used as measured by the PREPS grading system.

We undertake an annual audit to monitor our sustainability.

00_WAUGH_BTGOP_FM.indd 4 4/26/2017 10:54:19 AM

Contents

Acknowledgements vii

About the Editors and Contributors ix

About this Book 1

The Teachers’ Standards 7

1 The Teachers’ Standards 12

Yasmin Valli

2 Effective Learning 36

Wendy Jolliffe

3 Effective Teaching 54

Wendy Delf

4 Behaviour for Learning 66

Hilary Smith

5 Reflecting on Your Teaching 82

Julia Lawrence

6 Using Evidence to Inform Teaching 94

Paul Hopkins

7 Technology and the New Teacher 109

Paul Hopkins

8 Speech, Language and Communication Needs 127

Claire Head

00_WAUGH_BTGOP_FM.indd 5 4/26/2017 10:54:19 AM

Contents

vi

9 Building Academic Language in Learners of English as an Additional Language:

From Theory to Practical Classroom Applications 143

Kamil Trzebiatowski

10 Grammar, Punctuation and Spelling (GPS): Finding Your Way through

the First Year of Teaching 165

John Bennett

11 Supporting Struggling Readers and the Role of Phonics 179

Wendy Jolliffe

12 The Wider Role of the Teacher 199

Jonathan Doherty and David Waugh

13 Being Mindful of Teacher Well-being 216

Alison McManus

Conclusion 229

Index 231

00_WAUGH_BTGOP_FM.indd 6 4/26/2017 10:54:19 AM

4

Behaviour for Learning

Hilary Smith

This chapter

By reading this chapter you will develop your understanding of the following.

• The context and concept of Behaviour for Learning (B4L).

• The practical application of an intervention for children in a highly charged emotional state.

• Whole-class systems for establishing a positive learning environment.

06_WAUGH_BTGOP_CH_04.indd 66 4/26/2017 10:59:12 AM

4 Behaviour for Learning

67

Links to the Teachers’ Standards

This chapter will help you with the following Teachers’ Standards.

7. Manage behaviour effectively to ensure a good and safe learning environment

• Have clear rules and routines for behaviour in classrooms, and take responsibility for

promoting good and courteous behaviour both in classrooms and around the school, in

accordance with the school’s behaviour policy.

• Have high expectations of behaviour, and establish a framework for discipline with a range of

strategies, using praise, sanctions and rewards consistently and fairly.

• Manage classes effectively, using approaches which are appropriate to pupils’ needs in order

to involve and motivate them.

• Maintain good relationships with pupils, exercise appropriate authority, and act decisively

when necessary.

Introduction

The behaviour of children in schools or, rather, their misbehaviour, is frequently cited as one of the

main reasons for teachers leaving the profession early in their careers. Persistent disruption by one

or more children in the classroom, if it continues unabated, can lead to feelings of frustration and

inadequacy, and become a source of considerable anxiety and stress, especially for NQTs.

Advice and support on behaviour issues can come in many guises and it can be challenging for any

teachers, not just NQTs, to navigate the plethora of government documents, academic research,

advice from so-called ‘experts’ and various ‘top-tips for teachers’ to find what is statutory, what is

useful and what will most effectively support their classroom practice.

It would be impossible in one short chapter to provide definitive advice on such a broad and amor-

phous aspect of teaching as behaviour, so the focus here is to address the key concerns frequently

raised by new teachers who have developed ideas during their initial training on how they would

like to manage their own class (and how they would not like to) and who now have the opportunity

to build on those ideas and put them into practice.

The themes explored here focus on how to establish and maintain a positive learning environment

based on building meaningful relationships with children rather than depending on traditional

behaviourist methods to ‘manage’ them. It recognises the aspirations of those new to the profession

who wish be transformative in their teaching without controlling or suppressing children’s natural

curiosity and enthusiasm, but who also want robust, tried and tested, methods for providing order

and safety in their classroom, and effective systems that promote self-efficacy and self-regulation in

their young learners.

The chapter is divided into three parts. The first part sets the scene by providing the background

to the concept of Behaviour for Learning (B4L), explains how the conceptual framework works and

provides a case study to illustrate its practical application. The second part considers the issue of

06_WAUGH_BTGOP_CH_04.indd 67 4/26/2017 10:59:12 AM

4 Behaviour for Learning

68

attachment needs, an aspect of behaviour which teachers are increasingly concerned with, and

focuses on a particular intervention, emotion coaching, which has shown to be very effective in

calming down children who are in a highly charged emotional state. The third and final part reflects

on classroom codes and describes the use of class charters as a positive alternative to the traditional

practice of using ‘top-down’ rules.

Research/evidence focus

Behaviourism v. Behaviour for Learning

In 2004, Powell and Tod published A Systematic Review of how Learning Theories Explain Learning

Behaviour in School Contexts, which resulted in the development of a conceptual framework for

behaviour in schools with the term ‘learning behaviour’ being coined and the phrase ‘Behaviour

for Learning’ (B4L) becoming widely used by teachers and academics (Ellis and Tod, 2009). It also

spawned a government-funded website Behaviour4learning (now archived) which provided a compre-

hensive platform for research and evidence-based advice and guidance for teachers on all aspects of

behaviour in schools. It coincided with the Steer Report (DfES, 2005a), which made extensive recom-

mendations to support teachers in establishing and maintaining positive learning behaviour in their

classrooms. The focus of advice for teachers at that time recognised research into children’s motiva-

tion, self-esteem and self-regulation, and promoted approaches in schools that took account of social

and emotional aspects of learning and emotional literacy (DfES, 2005b). Since then, successive gov-

ernments have disregarded the B4L approach; it is not evident in the current Teachers’ Standards

(DfE, 2012a) or reflected in any recent government documents on behaviour (DfE, 2011, 2012b, 2016a).

The return to the rhetoric of discipline, designed to regenerate teachers as figures of authority, was

based on the popular notion that teachers were no longer being treated with respect and that behav-

iour in schools had become a source of serious concern with many children’s behaviour out of control

(Paton, 2014). Rooted in a behaviourist approach, official guidance on behaviour management tech-

niques since 2010 has relied on controlling children’s behaviour through rules, rewards and sanctions.

Critics comment that reverting to the language of‘misbehaviour’ and ‘punishment’ espouses a deficit

model of behaviour, which implies that children have to be controlled and ‘managed’ by adults before

any learning can take place and ignores the significant psychological evidence to the contrary (Adams,

2009; Rose etal., 2013; Ellis and Tod, 2015).

The Behaviour for Learning Conceptual framework

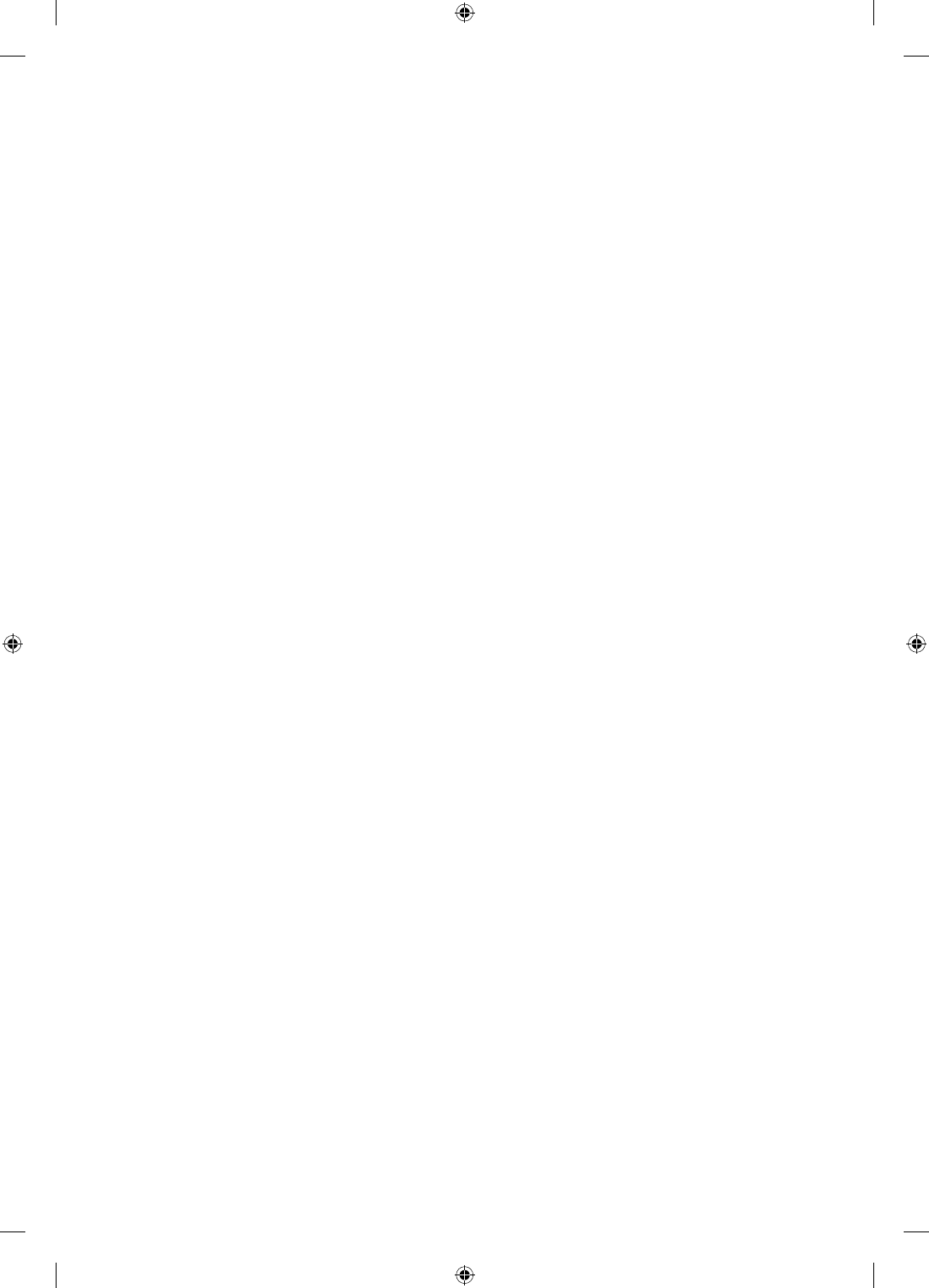

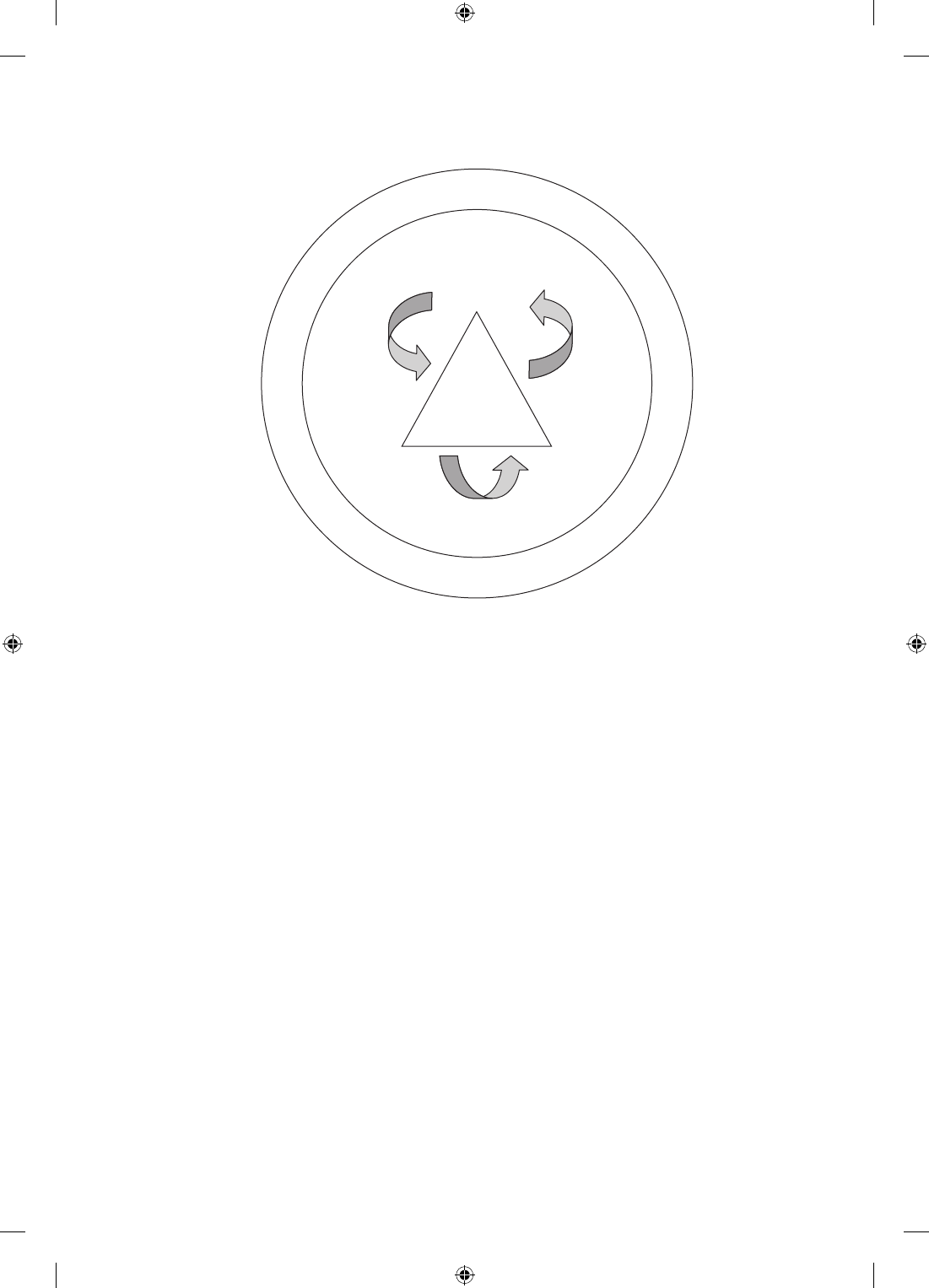

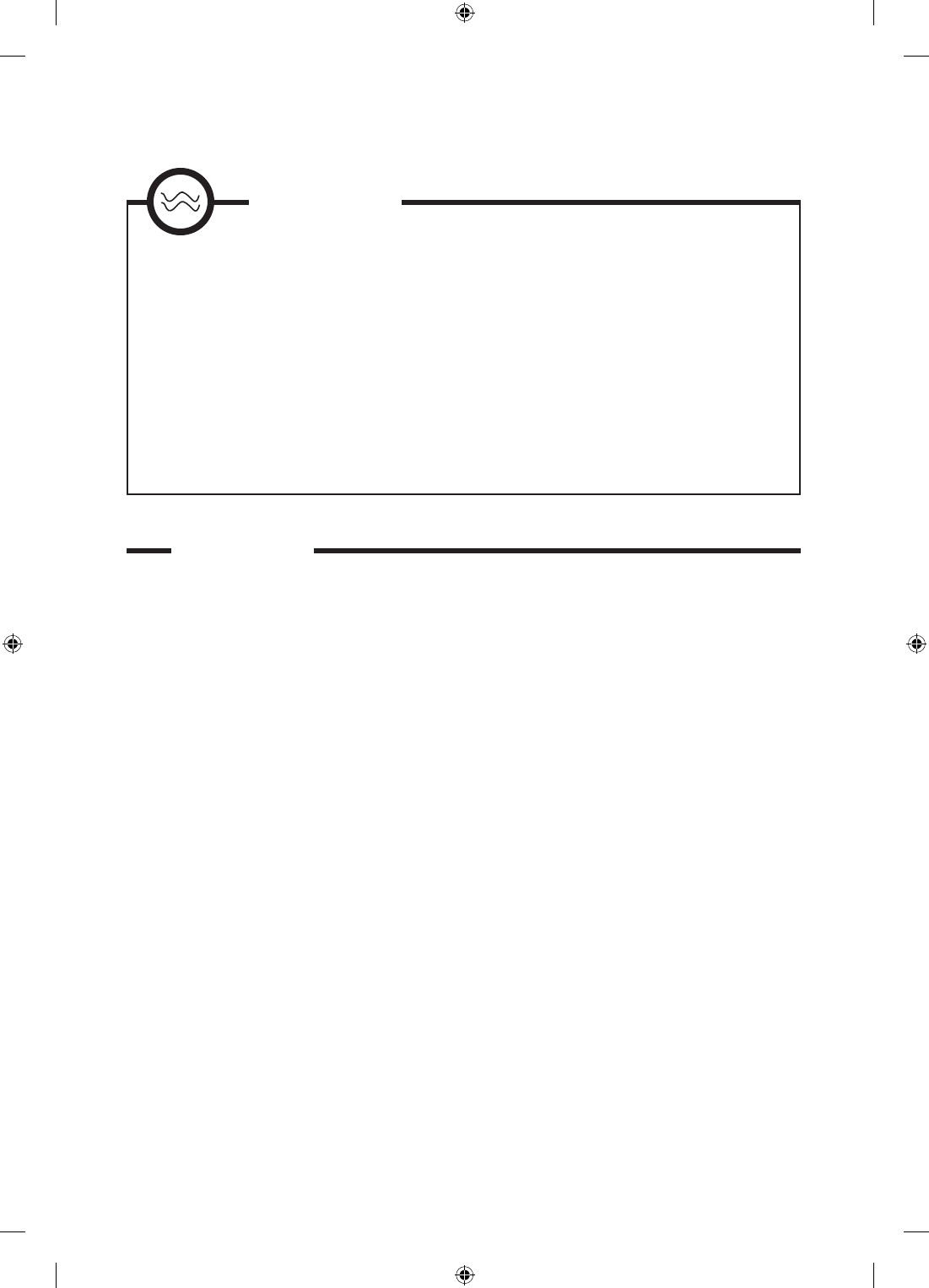

Ellis and Tod’s guiding framework for B4L (see Figure 4.1) emphasises the importance of relation-

ships with self, others and the curriculum, to encourage positive learning behaviour and a classroom

ethos where self-efficacy and agency can flourish.

The framework places learning behaviour at its centre, recognising that the shared aim is to pro-

mote behaviour that enables effective learning. It is placed within a triangle that represents the

social, emotional and cognitive factors which are addressed through the three relationships with

self (engagement), others (participation) and the curriculum (access). The arrows surrounding the

triangle indicate that the development of learning behaviour is a dynamic process and the three

06_WAUGH_BTGOP_CH_04.indd 68 4/26/2017 10:59:12 AM

4 Behaviour for Learning

69

relationships are interrelated. School ethos encompasses the triangle, and acknowledges the context

within which learning behaviour exists, and the terms outside of this boundary are a reminder that

learning does not take place in a vacuum and there are external influences which impact on pupils’

dispositions to learning.

In order to use the B4L framework as an effective tool, teachers need to give attention to each of the

three relationships which are summarised below.

Engagement (relationship with self)

Engagement refers to the internal thoughts, perceptions and feelings that learners hold about

themselves. Resistance to learning and challenging behaviour can occur when learners lack self-

awareness, have low self-esteem or have an impaired or inflated view of themselves and how others

see them. An inability to recognise their own emotional state or the feelings of others can also be a

significant barrier to positive learning behaviour. Teachers can address these issues at a classroom

level by using methods which encourage self-efficacy (helping children to have achievable goals),

metacognition (helping children to understand and reflect on how they know what they know) and

emotional literacy (helping children to recognise their emotions and respond appropriately to the

feelings of others).

Community/

Culture(s)

Policies

Participation

Relationship

with

Others

Learning

Behaviour

Access

Relationship

with the

Curriculum

Engagement

Relationship

with Self

FamilyServices

S

c

h

o

o

l

E

t

h

o

s

S

c

h

o

o

l

E

t

h

o

s

S

c

h

o

o

l

E

t

h

o

s

S

c

h

o

o

l

E

t

h

o

s

Figure 4.1 The Behaviour for Learning conceptual framework

Source: Ellis, S and Tod, J (2015) Promoting Behaviour for Learning in

the Classroom. Abingdon: Routledge, p11.

06_WAUGH_BTGOP_CH_04.indd 69 4/26/2017 10:59:12 AM

4 Behaviour for Learning

70

Participation (relationship with others)

Participation refers to the interactions that take place between peers, and between children and adults.

Its theoretical origins can be found in social learning theory (Bandura, 1971) and included in the

pathology of human behaviour (Maslow, 1976) as well as ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner,

1979). More recent neuroscientific research highlights social relationships, particularly with early

attachment figures, as being an essential component for developing neural pathways and crucial in

having the ability to engage in learning at all (Gerhardt, 2014; Music, 2016). To support this aspect of

B4L, teachers need to be proactive in creating an ethos where social engagement, cooperation and col-

laboration are encouraged, and a sense of belonging and group cohesion are supported.

Access (relationship with the curriculum)

Access refers to the way in which learners access, process and respond to the information imparted

to them. It requires teachers to consider how to transmit learning through active, dynamic interac-

tions that engage and challenge all children. It addresses the need to navigate through a largely

subject-based curriculum with prescribed age-related outcomes in a way that captures the interest

and absorption of self-initiated exploration. Revisiting the play-based principles of early years educa-

tion can provide a useful and significant direction here (Bennett and Henderson, 2013), as can the

suggestions for active learning (Vickery, 2014). When teachers encounter children who persistently

fail to be engaged with school work, they can support them through a range of strategies, includ-

ing openly exploring the child’s perspective with them, being more explicit about the purpose and

meaning of tasks, building in mechanisms that enable dialogue and negotiation of how goals can be

met, and establishing feedback systems that support self-worth (Higgins etal., 2007).

The three relationships outlined above, which comprise the B4L model, provide a structure for

teachers to use as a basis for establishing positive learning behaviours in their classroom and to trou-

bleshoot any challenging behaviour they may encounter.

The following case study illustrates an example of its use in solving a common classroom problem.

Case Study

Using the B4L framework to manage a boisterous reception class

Sarah is an NQT in a reception class in a one-form entry urban primary school. She successfully com-

pleted her final placement at the school while on her PGCE and was thrilled to have gained a post there.

Sarah’s first term went well and by November she felt confident that she had established positive rela-

tionships with the children in her class and set clear rules and routines. However, as the winter months

approached, she noticed that the atmosphere in the classroom had become quite boisterous. Each day

began calmly enough, but by mid-morning noise levels had risen considerably and by lunchtime there

was normally at least one incident of a child complaining of being shouted at or hurt by another child.

Sarah’s usual system of praising positive behaviour and disapproving of inappropriate behaviour was

becoming increasingly ineffective and she was feeling anxious about losing control of the class. She

06_WAUGH_BTGOP_CH_04.indd 70 4/26/2017 10:59:12 AM

4 Behaviour for Learning

71

began to increase the amount of sanctions she used – e.g. individual children lost their playtime if they

had hurt others – and she found herself raising her voice to counteract the loudness of the children.

However, this did little to improve the situation.

Sarah was advised by her induction mentor to step back and review what was happening, so she system-

atically made a series of focused observations of the class at particular times. She also asked her class

TA as well as her mentorto do some observations as well.

What emerged was that it was not the whole class causing the disruptive atmosphere, but a small group of

individual children who were independently becoming restless and off-task within a short time of going to

their table-top activities. These particular children were often fidgety and distracted each other by getting

out of their seats, chatting to others, calling out across the classroom and getting into minor conflicts.

Having identified the issues, Sarah used the B4L framework to try to problem-solve them. She addressed

each of the relationships in the framework – participation, engagement and access – and set up the fol-

lowing action plan.

Participation (relationship with others) To enable this group of children to interact with others more

positively,Sarah directed each of them to activities that required them to work in pairs or take turns and

interact in mutually supportive ways rather than to work individually on parallel tasks –e.g. setting up a

shopping role-play for counting money. She also introduced regular circle-time sessions for the whole

class, initially focusing on talking and listening, and being kind to each other.

Engagement (relationship with self) To encourage those children who were calling out and becoming

increasingly loud to understand and value quietness, Sarah introduced individual ‘quiet voice’ targets as

well as using the Too Noisy app (an application for electronic devices which monitors noise levels and

sets off a visual and audible alarm). She practised and modelled different noise levels with the children

in a fun way to help them recognise and control the volume of their voices, and gave particular attention

and praise to those who were the quietest.

Access (relationship with the curriculum) To increase the children’s motivation and interest in the tasks

set, Sarah made sure that each task had a physically active, multi-sensory element. Having previously lim-

ited the children’s access to the outside area because of the colder weather, she reinstated more activities

in the covered outdoor play space and made sure that every child had warm, waterproof clothing.

Within a couple of weeks, there was a marked change in the atmosphere in Sarah’s classroom; it was

calmer and quieter, and the children who had previously been rowdy and loud, were increasingly on-

task and more cooperative. The most successful strategies seemed to be using the Too Noisy app and

increasing the amount of opportunities to be active and outside.

Questions For Discussion/Reflection

1. What tensions might there be in using the B4L concept alongside traditional behaviourist

methods?

2. What other ways can the B4L framework be used to support positive learning behaviour?

3. How might the framework be shared with parents/carers?

4. How could the B4L framework be used to support individual children with challenging behaviour?

06_WAUGH_BTGOP_CH_04.indd 71 4/26/2017 10:59:13 AM

4 Behaviour for Learning

72

Attachment awareness

Children are not slates from which the past can be rubbed by a duster or a sponge, but human beings

who carry their previous experiences with them and whose behaviour in the present is profoundly

affected by what has gone before.

(Bowlby, 1951, p. 114)

The theory of attachment was first proposed by John Bowlby who believed that children need to

develop a secure attachment to their main care-giver during their early years in order to thrive emo-

tionally, physically and cognitively (Bowlby, 1951). Subsequent research, and in particular recent

advances in neuroscience, have confirmed and extended Bowlby’s theory such that it is now well

understood that not only do a child’s primary attachments lay the foundations for their capacity to

learn, but also that a child with secure attachment relationships will achieve higher academic attain-

ment, have better self-regulation and be more socially competent than their insecurely attached

counterparts (Rose etal., 2013).

Now that it is widely recognised that a child with an attachment disorder is highly likely to strug-

gle with all aspects of school life, some of the most challenging behaviours that teachers encounter

in classrooms today can be explained by children displaying the effects of insecure attachment

(Cozolino, 2013). Nevertheless, there is increasing evidence to suggest that teachers can make

a difference in ameliorating some of the impact of disordered attachment while at the same time

enhancing the learning experiences of all pupils (Tucker etal., 2002; Davis, 2003). This is partly

based on the suggestion that children can form multiple attachments (Sroufe, 1995; Robson, 2011)

and that an attuned, empathetic and responsive teacher can enable children to self-regulate their

behaviour through forming positive and secure relationships with them (Bergin and Bergin, 2009).

One method that has been shown to be effective in helping adults in school to build strong, sup-

portive relationships with children whose behaviour is challenging, and who struggle to focus on

learning or calm down when they are in a highly charged emotional state, is the use of emotion

coaching (Rose etal., 2015). It is an intervention that has had significantly positive results for chil-

dren with a range of behavioural disorders, but in particular for children with attachment issues.

Emotion coaching

The emotion coaching approach (or meta-emotion philosophy) was developed by John Gottman

(Gottman and DeClaire, 1997) and is based on the development of self-regulation through recogni-

tion of the emotions that are driving behaviour rather than the behaviour itself. It enables children

to understand and express their feelings in appropriate and more socially acceptable ways, supports

their capacity to refocus on learning when overwhelmed with strong feelings, and helps them to

become more emotionally resilient. The practice requires adults to ‘empathise and guide’ through

a series of suggested interactions. These have been broken down into three key steps by Rose etal.

(2015) who conducted a two-year pilot project on emotion coaching in schools in Wiltshire. The

steps include validating the child’s feelings in the first instance through an empathetic and sensi-

tive acknowledgement of their emotional state, without focusing on their behaviour. This has been

shown to have a powerful effect in calming children down and in physiological terms suggests that

06_WAUGH_BTGOP_CH_04.indd 72 4/26/2017 10:59:13 AM

4 Behaviour for Learning

73

simply recognising and engaging with the emotions being experienced can trigger the parasympa-

thetic system (Immordino-Yang and Damasio, 2007). Guidance comes in the form of the next step,

which may not always be necessary but which requires the establishment of boundaries, making it

clear that while accepting the emotions being felt, there are limits to what is acceptable behaviour.

This provides the child with direction and safety, supporting them in their understanding of what is

socially appropriate and the consequences of anti-social or harmful behaviour. The final step occurs

later, when the child has fully calmed down, and involves adult and child revisiting the incident

and problem-solving together how to avoid a recurrence. This engagement is designed to further

develop a trusting and nurturing relationship between the adult and child as well as give the child

the opportunities to ‘own’ their behaviour and better learn emotional self-regulation.

The following case study illustrates how emotion coaching made a significant difference to the rela-

tionship between a troubled boy and his teacher.

Case Study

Using emotion coaching to help a child with anger issues

Gemma is a Yr3 teacher in a large primary school with a mixed demographic. She has been teaching for

five years and was recently trained in emotion coaching techniques as part of a cluster-wide training and

found it particularly helpful when working with one child in her class, Tristan, whose angry outbursts

would often disrupt her teaching and create an atmosphere of fear and anxiety among the other children.

Tristan is the eldest of a family of four children and lives with his mum and stepdad. He has a different

father from his three siblings and although he has some contact with his own dad, it is intermittent and

unreliable. He has struggled with behaviour problems throughout his school career and while he does

not have a diagnosis of an attachment disorder, his mum has been very open about her difficulties in

bonding with him as a baby and her continued concern about his behaviour.

Knowing Tristan’s history, Gemma tried to establish a positive relationship with him from the outset

and the first term went quite well with only a few minor incidents, but soon Tristan’s old behaviour

patterns began to re-emerge. He started having outbursts of frustration, such as tearing up his work

or throwing equipment on the floor or shouting at other children, and when asked the reason for

his outbursts, would claim that the work he had been set was too hard or someone in the class had

insulted him or got in his way. Gemma’s response was to try to control the situation by using the class

sanctions – for example, telling Tristan that he had lost minutes from his Golden Time or would be stay-

ing in at playtime, but this often escalated into an angrier and occasionally aggressive response from

him, in one instance resulting in him ripping a whole classroom display from the wall and throwing a

chair across the room. This was considered sufficiently dangerous for the head teacher to be called.

She sent Tristan home and imposed a one-day fixed term exclusion, which had happened on a number

of occasions the previous year.

On Tristan’s return it was agreed that sanctions seemed to be ineffective and a different approach was

needed. Gemma was keen to try emotion coaching instead and planned the three-step method learned

on her training: recognising and validating feelings and showing empathy; setting limits on behaviour;

problem-solving with the child.

(Continued)

06_WAUGH_BTGOP_CH_04.indd 73 4/26/2017 10:59:13 AM

4 Behaviour for Learning

74

Gemma began by watching for early signs of Tristan becoming frustrated and would try to intervene quickly

by naming his emotions verbally and offering to talk them through by saying ‘I can see you’re getting very

frustrated and upset right now. That must be hard for you. Shall we talk about how you’re feeling?’ When

empathising with Tristan’s feelings, Gemma noticed that he began to calm down almost immediately and,

once calm, he was able to talk about his frustration and anger with her and they worked together to think of

some ways by which they could prevent his feelings from leading to damaging behaviours.

When Gemma was unable to identify the signs of Tristan’s frustration early enough and he had an

outburst and behaved inappropriately, instead of using a sanction Gemma would include limit-setting

statements in her response, such as ‘I can see you are angry now but it’s not OK to rip up your work or

shout at people. I need to help you to feel calm so that you don’t break anything or hurt anyone’, and

encourage Tristan to use some of the calming down techniques they had discussed and been practis-

ing. One of these was to sit in the classroom’s ‘Peaceful Place’ which was screened off from the rest of

the class and had tactile and sensory objects such as glass beads, colouring-in sheets, soft fabrics, gen-

tle music (to listen to through headphones) and cognitive prompts such as a display, photos and books

about feelings and problem-solving.

Emotion coaching did not eliminate Tristan’s problems completely, but Gemma noticed that the approach

did have a significant effect on the frequency of his outbursts and that he was able to calm down much

more quickly, usually without causing any damage. Over time, Tristan learnt to recognise for himself

when his feelings were getting the better of him and would seek out Gemma or another adult to talk

things through or would implement one of his calming down techniques.

Questions For Discussion/Reflection

1. What are the barriers to learning for children with attachment difficulties?

2. How can emotion coaching be included in everyday interactions?

3. What challenges are there in using emotion coaching for an individual while expecting other

children to follow the usual classroom rules?

4. How might emotion coaching be shared with parents/carers?

5. In what other ways can emotional literacy be developed in the classroom?

Research/evidence focus

Classroom codes

Creating a classroom code that reflects the school behaviour policy but is personalised for each class

of children can be a really effective way to establish and maintain positive learning behaviour. The cur-

rent view in positive psychology is that when classroom rules are made explicit, children experience a

(Continued)

06_WAUGH_BTGOP_CH_04.indd 74 4/26/2017 10:59:13 AM

4 Behaviour for Learning

75

sense of safety and well-being which enhances their capacity to learn (Swinson and Harrop, 2012). Porter

(2014) claims that 89 per cent of disruptive behaviours can be prevented when teachers consistently

provide clear behaviour expectations. Articulating desired behaviours in an accessible and positive way

removes uncertainty for children who feel anxious or vulnerable about what is expected of them (and

what might get them into trouble). It also enables teachers to feel more confident that their behaviour

expectations will be met (Holmes, 2009). Government guidance is unequivocal that school behaviour

policies need to include a set of rules and Charlie Taylor’s guidance (DfE, 2011) exhorts teachers to

Display school rules clearly in classes and around the building. However, government advice on how to

develop these rules is minimal and mostly set within the context of rewards and sanctions (DfE, 2016a),

rules, rewards and sanctions being referred to by Ellis and Tod as the behavioural trinity (2009, p151).

More recent advice offered to trainee teachers from the ‘Behaviour Guru’ Tom Bennett does not refer to

classroom rules as such, but in his 3 Rs of the Behaviour Curriculum (DfE, 2016b) he recommends that

teachers communicate shared values and behaviours openly, and regularly model and reinforce expecta-

tions and boundaries.

Rights respecting schools and classroom charters

Most authors who provide advice on how to create an effective classroom code agree on similar

principles – namely, that the expectations should be inclusive, explicit, few in number and phrased

positively (Dix, 2007; Holmes, 2009; Chaplain, 2014; Robinson etal., 2016). They also suggest that

when children have some involvement in the design of their classroom code, they feel a sense of

ownership and are more likely to be motivated not only to cooperate fully themselves, but also to

encourage their peers to as well. Rogers (2012) goes further and promotes the use of a framework of

rights, responsibilities and rules based on an agreed set of values shared by the whole school com-

munity. He believes that behaving well is the joint responsibility of all class members and that the

most fundamental rights of a classroom member are those of respect and fair treatment ... they relate to due

responsibility and fair and agreed rules (2012, p15).

The theme of rights and responsibilities as a basis for respectful behaviour in schools has been estab-

lished in England by UNICEF (United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund) through

an award known as the Rights Respecting Schools (RRS) Award (UNICEF(a)) which promotes the UN

Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989). The award was the result of an initiative introduced

in Hampshire in 2002 to encourage human rights education and develop dispositions and behav-

iours that support social justice within the school community (Covell etal., 2010). Results from this

initiative showed that in participating schools, children demonstrated higher levels of engagement

in learning, more respectful behaviour and greater participation in school life than children in non-

participating schools (Covell and Howe, 2008).

One of the key features of schools that follow the RRS agenda is that, consistent with children’s

rights to participation in matters that affect them (Article 12 of the Convention), school rules and

behaviour codes are decided democratically, giving children opportunities to have a voice in deci-

sions that affect them, and although the remit for the RRS award goes considerably beyond setting

up classroom codes of behaviour, it does provide guidance and support on how to create and use

a classroom charter (UNICEF(b)). In ‘rights-respecting’ schools, at the beginning of each year, chil-

dren and teachers work together in each class to create an agreement of everyone’s rights and their

06_WAUGH_BTGOP_CH_04.indd 75 4/26/2017 10:59:13 AM

4 Behaviour for Learning

76

corresponding responsibilities. These may include such statements as we have the right to be treated

fairly and the responsibility to treat each other fairly; we have the right to be heard and the responsibil-

ity to listen to and respect other people’s ideas; we all have the right to learn, so we will help each other

(Covell, 2013, p42).

The following case study illustrates how the use of a class charter helped a teacher establish positive

learning behaviour in his classroom.

Case Study

Setting up a class charter to establish behaviour expectations

Craig’s first career was as a graphic designer. He is now into his second year of teaching and takes every

opportunity to bring his creative skills into the classroom. He has an energetic, positive approach and his

lessons are often lively and engaging, but during his NQT year he struggled to maintain positive behav-

iour and cooperation in his class and often felt that he was not fully in control of what was happening. He

began his second year in a Year 5 class in a different school and was keen to establish clear behaviour

expectations from the outset.

The school that Craig moved to is a ‘Rights Respecting School’ (RRS) and he was advised to fol-

low the UNICEF guidance on how to establish a class charter in the first week after the summer

holidays. Using the school’s RRS resources, he planned a series of lessons designed around the UN

Convention of the Rights of the Child (CRC): recapping the articles of the CRC, their importance and

why they exist; discussing with the children which articles to base their class charter on; agreeing

the wording of the charter and designing it; signing the charter and displaying it in the classroom.

The resulting agreement consisted of a list of ‘rights’ with direct links to articles in the CRC, and a

list of ‘responsibilities’ which every member of the class (including Craig and his teaching assistant,

Michelle) signed.

Craig wanted the charter to be meaningful and relevant to all the children in his class, so over the next

two weeks he used a carousel of inclusive activities: drama and role-play, creative writing, photography,

artwork and game design to bring the charter alive and encourage every child to be involved and to feel

a sense of ownership of it. Once the charter was established, he regularly referred to it. For example,

acknowledging children for behaviour that specifically related to one of their class articles: ‘I can see

you two are really listening to each other’s ideas. Well done for following Article 13!’; or using it to remind

children whose behaviour was disrespectful or inappropriate that they were breaking their agreement:

‘I can see that Asif is hurt by what you just said. That is not in keeping with our responsibility to be kind

and respectful to everyone.’ As well as modelling the language of the charter himself, Craig encouraged

the children to use the same words when reflecting on their own behaviour or describing the behaviour

of others following an incident. In this way, he was able to reinforce the behaviour expectations by con-

sistently relating children’s actions to the agreement they had all made.

Although the UNICEF guidance states that a class charter is not intended to be used as a behaviour man-

agement tool, Craig found that by combining it with guidance from the school behaviour policy he was

able to use it to generate a menu of rewards for children who followed the class charter and an agreed

set of consequences if any of the articles were broken. He had a round of discussions with the children,

giving them choices from a range already agreed in the school behaviour policy, until they came to

a consensus about the rewards and consequences they thought were fair for their class. These were

06_WAUGH_BTGOP_CH_04.indd 76 4/26/2017 10:59:13 AM

4 Behaviour for Learning

77

displayed on a poster alongside the charter and included rewards such as a ‘teacher text’ to a parent/

carer’s mobile phone, extra playtime, and an end-of-term class pizza party, as well as the regular whole-

school rewards of house points, afternoon tea with the head teacher and the ‘Big Yellow Duck Award’

(given for particular acts of kindness). Consequences for unkind or uncooperative behaviour were cho-

sen with varying degrees of severity ranging from missing five minutes of playtime or working alone on

the ‘Thinking Table’, to doing ‘community service’ (which involves doing jobs around the school during a

series of lunchtimes) or being placed ‘on report’. In the spirit of being a Rights Respecting School, these

consequences also include opportunities for reparation and supporting children to make amends for any

harm or damage caused.

Craig continued to use the charter, and the rewards and consequences system, on a daily basis and by

the end of term 2 he was pleased to notice that he had been able to teach exciting, highly active and

creative lessons without being concerned that children would be uncooperative or challenging, as had

happened with his previous class. He said ‘the class charter has really made a difference to how I think

about behaviour ... it’s based on everyone respecting each other and looking out for each other ... the

children in my class have ownership of it and are cooperative because they want to be, they make that

choice themselves, not because I’m some strict disciplinarian that makes them do what I want. I’m so

glad I’ve found a way to have good behaviour in my classroom without becoming the stereotypical male

teacher who is “good with discipline” just because I’m a bloke.’

Questions For Discussion/Reflection

1. What are the benefits and disadvantages of using rewards and sanctions?

2. How could the RRS guidance be used in other ways to support positive learning behaviour?

3. What challenges might there be in creating a class charter?

4. What are the rights and responsibilities of the teacher in terms of behaviour in the classroom?

Chapter Summary

This chapter has provided a summary of the context for Behaviour for Learning, explained the

conceptual framework with suggestions on how it can be applied, and given an illustration of its

use as a classroom intervention. By focusing on B4L, it offers a blueprint for creating a positive

learning ethos without resorting to traditional methods of discipline and control. The chapter has

also considered the importance of attachment issues and proposed emotion coaching as a strat-

egy to support children in a highly charged emotional state, a method that can empower children

who are in distress and give teachers greater confidence in using this intervention to support

them. The practice of creating a classroom code or charter also offers children greater ownership

and opportunities for self-regulating their behaviour. It is a positive and effective alternative to

imposing ‘top-down’ rules and further endorses the message from B4L that behaviour manage-

ment is ‘all about relationships’ (Holmes, 2009, p89).

06_WAUGH_BTGOP_CH_04.indd 77 4/26/2017 10:59:13 AM

4 Behaviour for Learning

78

Some final points

• The strategies suggested here are likely to be more powerful if shared with parents/carers, particularly for

those who are coping with challenging behaviour from their children at home. Consider how each method

might be used to forge positive links between home and school.

• School behaviour policies frequently focus on rewards and sanctions, do not take account of the

importance of relationships and are rarely written in consultation with children. Reflect on the way

in which a behaviour policy is translated into practice and how it might be developed and used more

positively and effectively.

• Behaviour for Learning, emotion coaching and the Rights Respecting Schools agenda all take a pro-active

and positive stance towards children’s behaviour. However, the language and practice of behaviourism are

still prevalent in schools and even the word ‘behaviour’ persistently has a negative connotation. Consider

how this might be challenged and how teachers might be encouraged to take a more optimistic approach.

Further reading

Ellis, S and Tod, J (2015) Promoting Behaviour for Learning in the Classroom: Effective Strategies, Personal

Style and Professionalism. Abingdon: Routledge.

This latest book by Ellis and Tod provides further insights into the principles and practice of the B4L

conceptual framework. It draws on teachers’ everyday experiences of interactions and relationships

in the classroom and is designed to appeal to those new to the profession.

Gottman, J and DeClaire, J (1997) Raising an Emotionally Intelligent Child: The Heart of Parenting.

New York: Prentice-Hall.

Although now nearly 20 years old, and addressed to parents, this is Gottman’s seminal work on

emotion coaching and a ‘must read’ for anyone who wants to understand more about this strategy

and how to practise it.

Robins, G (2012) Praise, Motivation and the Child. Abingdon: Routledge.

This highly accessible book written by a former deputy head teacher brings clarity to the theory and

practice of behaviourism, constructivism and positive psychology. It considers the use of extrinsic

and intrinsic rewards, and gives children a voice in expressing what their motivations are and how

teachers can best support them in developing positive learning behaviours.

Useful websites

Attachment Aware Schools: http://attachmentawareschools.com

This website provides a comprehensive introduction to attachment and the implications for learning

and behaviour, as well as links to further resources, including guidance on emotion coaching.

Behaviour4learning: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20101021152907/http:/www.

behaviour4learning.ac.uk

06_WAUGH_BTGOP_CH_04.indd 78 4/26/2017 10:59:13 AM

4 Behaviour for Learning

79

This website provides background research, resources and ideas for teachers in all aspects of the B4L

approach. Although now part of the national archive, its content is still highly relevant for today’s

classrooms. NQTs may find the ‘26 scenarios’ particularly useful.

Behaviour2Learn videos: www.youtube.com/user/Behaviour4Learning

This collection of video clips covers a broad range of behaviour issues from practical classroom tips

to debates on how best to respond to challenging behaviour.

Rights Respecting Schools: www.unicef.org.uk/rights-respecting-schools/about-the-award/what-

is-the-rights-respecting-schools-award/

This link takes you to the UNICEF site that provides all the information on the RRS award, including

how to create a class charter.

References

Adams, K (2009) Behaviour for Learning in the Primary School. Exeter: Learning Matters.

Bandura, A (1971) Social Learning Theory. New York: General Learning Press.

Bennett, V and Henderson, N (2013) Young children learning: the importance of play. In Ward, S

(ed.) A Student’s Guide to Education Studies (3rd edn). Abingdon: Routledge, pp168–77.

Bergin, C and Bergin, D (2009) Attachment in the classroom. Educational Psychology Review, 21:

141–70.

Bowlby, J (1951) Maternal care and mental health. Bulletin of the World Health Organisation, 3:

355–534.

Bronfenbrenner, U (1979) The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Chaplain, R (2014) Managing classroom behaviour. In Cremin, T and Arthur, J (eds) Learning to Teach

in the Primary School. London: Routledge, pp181–201.

Covell, K (2013) Children’s human rights education as a means to social justice: a case study from

England. International Journal for Social Justice, 2(1): 35–48.

Covell, K and Howe, RB (2008) Rights, respect and responsibility: final report on the county of

Hampshire Rights Education Initiative. Hampshire County Council.

Covell, K, Howe, RB and McNeil, JK (2010) Implementing children’s human rights education in

schools. Improving Schools, 13(2): 1–16.

Cozolino, LJ (2013) The Social Neuroscience of Education: Optimising Attachment and Learning in the

Classroom. London: WW Norton.

Davis, HA (2003) Conceptualizing the role and influence of student–teacher relationships on chil-

dren’s social and cognitive development. Educational Psychologist, 38(4): 207–34.

Department for Education (2011) Getting the simple things right: Charlie Taylor’s behaviour check-

lists. Available at: www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/571640/

Getting_the_simple_things_right_Charlie_Taylor_s_behaviour_checklists.pdf (accessed November 2016).

06_WAUGH_BTGOP_CH_04.indd 79 4/26/2017 10:59:13 AM

4 Behaviour for Learning

80

Department for Education (2012a) Teachers’ Standards: guidance for school leaders, school staff

and governing bodies. Available at: www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_

data/file/301107/Teachers__Standards.pdf (accessed November 2016).

Department for Education (2012b) Ensuring good behaviour in schools. Available at: www.gov.

uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/239943/Ensuring_Good_Behaviour_

in_Schools-summary.pdf (accessed November 2016).

Department for Education (2016a) Behaviour and discipline in schools: advice for head teach-

ers and schoolstaff. Available at: www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/

file/488034/Behaviour_and_Discipline_in_Schools_A_guide_for_headteachers_and_School_Staff.pdf

(accessed November 2016).

Department for Education (2016b) Developing behaviour management content for initial teacher.

Available at: www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/536889/

Behaviour Management_report_final__11_July_2016.pdf (accessed November 2016).

Department for Education and Skills (2005a) Learning behaviour: the report of the practitio-

ners group on school behaviour and discipline (the Steer Report). Nottingham: DfES. Available at:

http://cw.routledge.com/textbooks/9780415485586/data/BehaviourTheSteerReport.pdf (accessed

November 2016).

Department for Education and Skills (2005b) Excellence and enjoyment: social and emotional

aspects of learning: guidance. Available at: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/2011080

9101133/nsonline.org.uk/node/87009 (accessed November 2016).

Dix, P (2007) Taking Care of Behaviour: Practical Skills for Teachers. Harlow: Pearson Education.

Ellis, S and Tod, J (2009) Behaviour for Learning: Proactive to Behaviour Management. London: David

Fulton.

Ellis, S and Tod, J (2015) Promoting Behaviour for Learning in the Classroom. London: Routledge.

Gerhardt, S (2014) Why Love Matters: How Affection Shapes a Baby’s Brain (2nd edn). London: Routledge.

Gottman, J and Declaire, J (1997) Raising an Emotionally Intelligent Child: The Heart of Parenting.

New York: Prentice-Hall.

Higgins, S, Baumfield, V and Hall, E (2007) Learning skills and the development of learning

capabilities report. In Research Evidence in Education Library. London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science

Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London.

Holmes, E (2009) (2nd edn) The Newly Qualified Teachers Handbook. London: Routledge.

Immordino-Yang, M and Damasio, A (2007) We feel, therefore we learn: the relevance of affective

and social neuroscience to education. Mind, Brain and Education Journal, 1(1): 310.

Maslow, A (1976) The Farther Reaches of Human Nature. New York: Penguin Books.

Music, G (2016) Nurturing Natures: Attachment and Children’s Emotional, Sociocultural and Brain

Development (2nd edn). London: Routledge.

Paton, G (2014) Ofsted: an hour of teaching each day lost to bad behaviour. Available at: www.

telegraph.co.uk/education/educationnews/11119373/Ofsted-an-hour-of-teaching-each-day-lost-to-bad-

behaviour.html (accessed November 2016).

06_WAUGH_BTGOP_CH_04.indd 80 4/26/2017 10:59:13 AM

4 Behaviour for Learning

81

Porter, L (2014) (3rd edn) Behaviour in Schools: Theory and Practice for Teachers. Maidenhead: Open

University Press.

Powell, S and Tod, J (2004) A Systematic Review of How Learning Theories Explain Learning Behaviour in

School Contexts. London: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University

of London.

Robinson, C, Bingle, B and Howard, C (2016) Surviving and Thriving as an NQT. Northwich:

Critical Publishing.

Robson, S (2011) Attachment and relationships. In Moyles, J, Georgeson, J and Payler, J (eds) Beginning

Teaching, Beginning Learning: In Early Years and Primary Education. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Rogers, B (2012) (3rd edn) You Know the Fair Rule. Harlow: Pearson.

Rose, J, Gilbert, L and Smith, H (2013) Affective teaching and the affective dimensions of learn-

ing. In Ward, S (ed.) A Student’s Guide to Education Studies (3rd edn). Abingdon: Routledge, pp178–88.

Rose, J, McGuire-Snieckus, R and Gilbert, L (2015) Emotion coaching – a strategy for promoting

behavioural self-regulation in children/young people in schools: a pilot study. The European Journal of

Social and Behavioural Sciences, XIII.

Sroufe, A (1995) Emotional Development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Swinson, J and Harrop, A (2012) Positive Psychology for Teachers. London: Routledge.

Tucker, CM, Zayco, RA, Herman, KC, Reinke, WM, Trujillo, M and Carraway, K (2002)

Teacher and child variables as predictors of academic engagement among low-income African

American children. Psychology in the Schools, 39: 477–88.

UNICEF (a): Rights Respecting Schools Award. Available at: www.unicef.org.uk/rights-respecting-

schools/about-the-award/what-is-the-rights-respecting-schools-award/ (accessed November 2016).

UNICEF (b): Classroom Charters. Available at: www.unicef.ca/sites/default/files/imce_uploads/

UTILITY%20NAV/TEACHERS/DOCS/GC/Classroom_Charters_Instructions.pdf (accessed November

2016).

UNICEF (1989) The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Available at:

http://353ld710iigr2n4po7k4kgvv-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/05/UNCRC_

PRESS200910web.pdf (accessed November 2016).

Vickery, A (ed.) (2014) Developing Active Learning in the Primary Classroom. London: Sage.

06_WAUGH_BTGOP_CH_04.indd 81 4/26/2017 10:59:13 AM